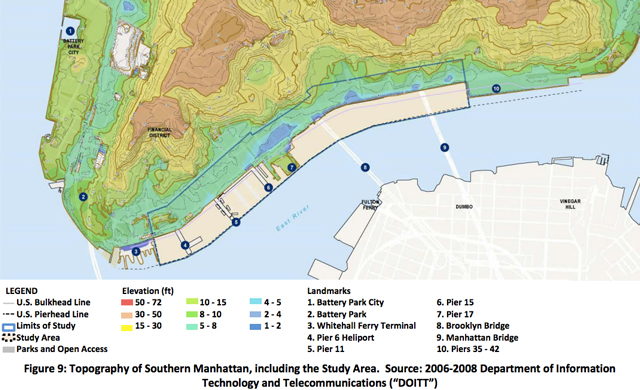

Last summer, as part of a plan to protect New York from flooding due to climate change, the Bloomberg administration proposed building “Seaport City,” a Battery Park City-type development on the East River in Lower Manhattan. Landfill would be used to create a “multi-purpose levee”—19 feet high at its peak and reaching 500 feet into the East River—which would not only shield inland areas from floodwaters, but also support new commercial and residential development. Over time, the revenues from new development would help pay for flood-mitigation projects.

The idea is as intriguing as it is ambitious. To think: new land in Lower Manhattan! This alone is certainly enough to pique the interests of the city’s power elite. What’s more, it is perfectly clear that something must be done to protect Lower Manhattan from future flooding. The fact that new development could help finance flood protection is the cherry on top, and the primary rationale for Seaport City is the city’s belief it would be “self-financing.”

Five billion in city funds have already been put aside for resiliency measures; the federal government will kick in another $10 billion. Still, the city is $4.5 billion short of what it estimates will be needed to make New York stronger against climate change.

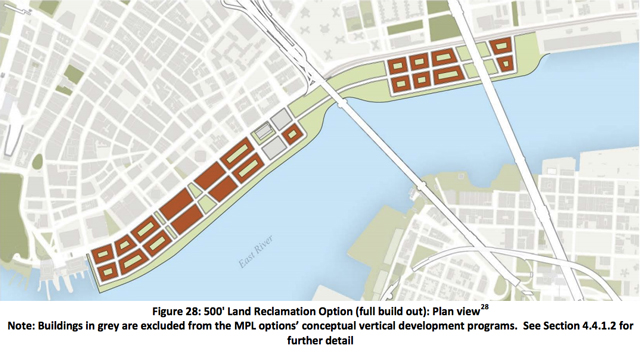

According to a report by the city’s Economic Development Corporation, the Seaport City concept could indeed be self-financing. The presentation details six different proposals for storm protection, ranging from a series of waterproof barriers and flood-fortified buildings along the existing shoreline to 500 feet of new land extending into the East River with new offices and apartments on top.

All six options—including the least ambitious—were “designed to achieve the same level of flood protection,” according to the study. But only two options would be self-financing. They would both extend 500 feet into the East River, with one featuring a destination park between the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges.

According to the EDC’s analysis, the “North Park” option is preferred, not only because it would bring in the biggest surplus–$900 million that could be used for other resiliency projects—but would also allow redevelopment projects at Pier 17 and the New Market Building to proceed.

This project would accommodate 12,000 new units of housing, 6.3 million square feet of commercial space, 1.4 million square feet of community facilities, and 26 acres of open space. Most of the new towers would rise south of Maiden Lane, with some smaller-scale development just north of Pier 17 and on another parcel north of the Manhattan Bridge.

It’s likely the city would take on most of the initial risk, establishing an authority or development corporation that would then issue bonds. Battery Park City and Hudson Yards offer precedents. In both cases a new entity was established to both finance the project and to act as a partner with the private sector. A private developer would purchase the right to develop, along with payments in lieu of taxes.

But will any developers bite? If things don’t go as planned at Hudson Yards there might not be much appetite for such a grand project. Will there even be demand for over six million square feet of new office space in lower Manhattan in the next 25 years? The city’s Independent Budget Office predicts that New York City will need anywhere between 30 and 87 million square feet of new office space by 2040, but with such a wide margin, there is a wide potential for errors.

Developers would also have to contend with NIMBYs, as well as building owners upset about losing river views. The project has already drawn the ire of Community Board 3, some of whom were skeptical of the city’s motives. Demands will also include affordable housing.

Could Lower Manhattan get the same level of flood protection for much less hassle? One proposal, called the Big U, would wrap around Manhattan from 57th on the west side, south to the Battery, and back up to 42nd. Along the East River in lower Manhattan, the Big U plan would rely on a “series of pavilions” underneath the FDR Drive and deployable flood barriers. The Big U would not support new apartments and offices.

According to the EDC’s study, these measures would not be sufficient by themselves, but would rather “act as an interim flood protection system.” Land reclamation is the best long-term solution, the report asserts, because it is “passive in nature, consisting only of earthen levee.”

Ultimately, a vision that plans for the worst-case scenario would most benefit New York. The ice sheets and glaciers of Antarctica and Greenland are receding faster than anticipated, potentially yielding a future with significantly higher sea levels.

Land reclamation does seem to be the city’s best option for flood protection, offering a permanent, 19-foot barrier. Building Seaport City would thus satisfy several city goals: job creation, new housing, and resiliency.

Mayor de Blasio has yet to weigh in on the merits of the Seaport City concept since learning of its feasibility. The mayor has positioned himself as pro-development and pro-density. Seaport City would certainly be big, and would have more than twice the number of apartments set to rise at Hunter’s Point South, currently the city’s largest residential project.

Building Seaport City would be a major headache for any mayoral administration, and its creation will require a mayor with mettle. Reward is seldom gained without risk — but if New York does not swim, it will surely sink. And if that’s the case, then everyone loses.

For any questions, comments, or feedback, email newyorkyimby@gmail.com

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews