In 2010, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie announced the cancellation of the Access to the Region’s Core (ARC) tunnel, which would have built two new commuter rail tracks beneath the Hudson River between New Jersey and New York Penn Station, doubling the current two shared by Amtrak. He diverted $3 billion of state and Port Authority contribution to the state’s highways, avoiding a fuel tax hike. The response from (most of) the region’s public transit supporters was strongly negative, with lingering animosity stirred up by Christie’s endorsement of a panel’s recommendation to build another trans-Hudson crossing. And yet, when Christie first suspended the project before finally canceling it, I considered it a minor celebration.

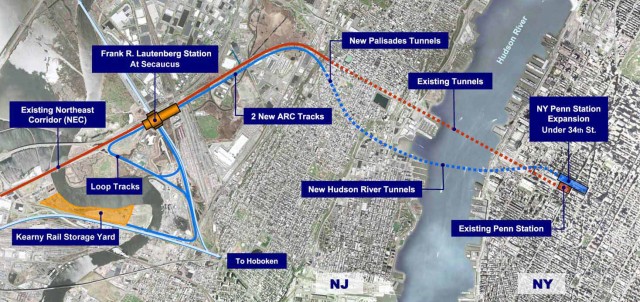

The ARC project had a fatal, fundamental design flaw: it would have been built according to early 20th century commuter rail principles, with a deep, disconnected dead-end terminal instead of a more efficient connection to existing tracks and possible future tunnel through to Grand Central Terminal. The new tunnel would not have connected to any existing infrastructure within Manhattan, but instead instead dump commuters into a six-track, bilevel cavern 170 feet beneath the ground next to Penn Station.

In this way the project shared a key design feature of East Side Access, also being constructed with a new cavern terminal beneath Grand Central, rather than to the existing station. Because of the expense of building such a massive underground structure, cost estimates grew considerably before construction. When the ARC project was first studied in the Major Investment Study in 2003, the cost estimates were about $3 billion. By the time construction began in 2009, the price tag had risen to $8.7 billion. This is similar to East Side Access’s cost overruns, from $4.3 billion initially to $10.8 billion today.

Even then, after ground had just broken, there was a better plan. When ARC was first studied, there were multiple alternatives explored in what was known as a major investment study, all with a pair of tracks into the West Side, but diverging afterward. The chosen alternative, termed Alt P (for Penn), was to include the new cavern. But another option – Alt G (for Grand Central) – would have instead included a new connection between Penn Station and Grand Central, fusing the suburban infrastructure into something that could be more easily turned into rapid transit, offering more utility to commuters.

It was estimated to have about the same upfront cost as Alt P and higher ridership, but was eliminated because of possible construction difficulties, as well as friction with Metro-North (the exact justification is a bit hazy, since the Port Authority and New Jersey Transit have refused repeated requests to release the full study and the MTA claims it lost the multimillion-dollar document). Before Christie canceled ARC and diverted the funds to roads, some transit activists, such as George Haikalis of the Institute for Rational Urban Mobility, hoped he would announce a change to Alt G, but to no avail.

Alt G would have enabled a feature of many European and Asian suburban rail networks, but which exists in the U.S. only in Philadelphia: through-running. Commuter trains could have come in from New Jersey, made stops at both Penn and Grand Central on both sides of the city, and then continued north as Metro-North trains, offering service a bit more like express subways. Even with the current infrastructure, New Jersey Transit trains could continue east as LIRR trains, giving Long Island access to Newark and New Jersey riders access to Flushing and Jamaica.

Similar systems abroad have been wildly successful. For example, in the late 1960s, the Paris region began to build dedicated tunnels permitting such through-running, creating a system called the RER, which has 2.7 million weekday riders today. Its first line, the RER A, has nearly a million daily riders, more than any Métro route in the city.

There are minor technical difficulties in implementing such a system in New York, but all are solvable. The trains use different electrical systems, but there exist dual-voltage trains, running today on Metro-North’s New Haven Line. Penn Station has congestion on its platforms, in addition to congestion in the existing access tunnel across the Hudson, but train dwell times can be reduced if the train continues onward to a further destination, rather than terminating and turning back; this would allow new tunnels to be used to their full extent even without additional tracks at Penn.

The operating railroads are different, but this also happens in Paris, and there the drivers change at the boundary between two operators, which takes about a minute. These solutions are implemented alongside integrated tickets and schedules across the entire Paris metro area. But due to hardened bureaucratic lines – there’s scant integration even between MTA properties like Metro-North and the Long Island Railroad, nevermind non-MTA ones like New Jersey Transit – New York has no such coordination.

But despite these problems, the region may still get a better tunnel in the future, in the form of Amtrak’s Gateway project, with the railroad began promoting soon after ARC was canceled. Gateway is similar to Alt G, but would also condemn a full Manhattan block to build additional tracks for Penn Station, at a greater for a total cost of $16 billion, including additional construction between the tunnel portal and Newark that Amtrak was planning to build independently before Christie canceled ARC. It would not include a new connection to Grand Central, but at least the new trans-Hudson tunnel would terminate in such a position that a tunnel to the east side could be built at a later date, unlike the less flexible ARC design.

The region can do much to reduce Gateway’s costs by eliminating unnecessary scope, such as the condemnation of land for new tracks. But if it can find the money for Gateway, the delayed Hudson tunnel would be much better for commuters than ARC.

While it would have been better if Christie hadn’t waited so many years after canceling ARC to get behind a better plan – redirecting the state’s ARC contribution to a better plan rather than using it to keep the state’s gas tax low – what New York and New Jersey could get in the form of Gateway would be worth the wait.

Alon Levy is currently a post-doc fellow in mathematics at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, and was previously a New York City resident while at Columbia University. He blogs about transit and other urbanist issues at Pedestrian Observations.

Talk about this project on the YIMBY Forums

For any questions, comments, or feedback, email newyorkyimby@gmail.com

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews