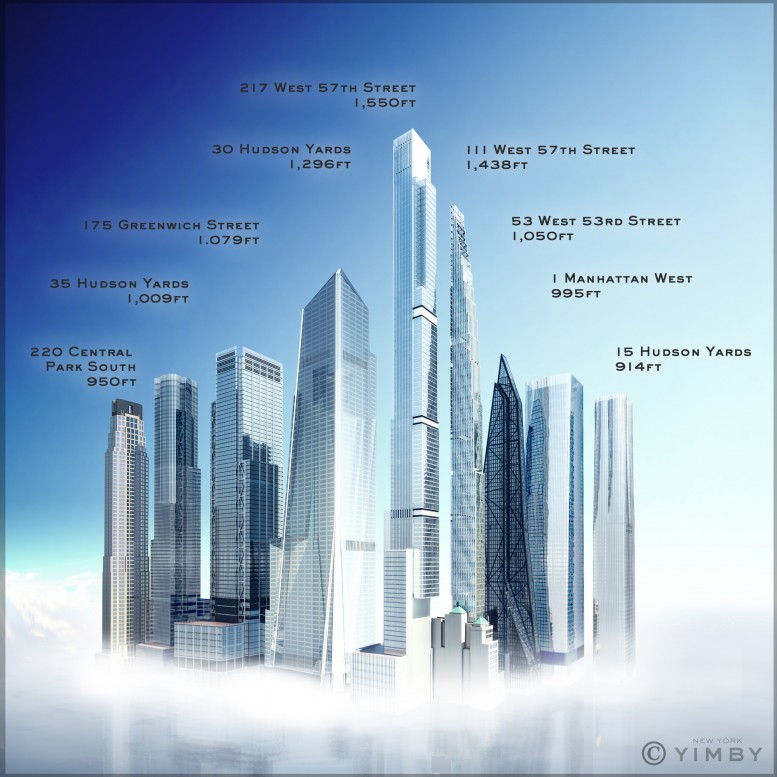

The rise of the supertalls has been several years in the making, and One57, 432 Park Avenue, and One World Trade Center have offered a preview of the increasingly gargantuan changes taking place across New York City. But 2016 will mark the start of a new era for the city’s skyline. With six supertalls of 300 meters (984 feet) or greater now rising, the city’s total number of such buildings will nearly double, from seven to thirteen. Yesterday, the New York Post featured YIMBY’s compilation of the towers, and today we wanted to give our own rundown on the image (hi-res at link) and its implications for our continually-changing city.

Manhattan long held the title of the world’s most impressive skyline, with the boom of the 1920s cementing the island’s status as the skyscraper capital of the globe. The Chrysler Building (at 1,046 feet) and the Empire State Building (at 1,250 feet) marked the city’s first official supertalls, and the ESB held the title of the world’s tallest building until the Twin Towers of the original World Trade Center were completed in the early 1970s.

Following 2001, the uptick in supertall construction began gradually, and was exclusively focused on office development. Both the Bank of America Tower (1,200 feet) and the New York Times Building (1,050 feet) rose prior to the 2008 financial crash, but it wasn’t until 2012 that One World Trade Center topped-out to reclaim the mantle of king of the Downtown and overall Manhattan skylines.

Given all this, it is surprising that critics deride some of the new buildings as “Hong Kong on the Hudson” when cities like Hong Kong have long looked to New York as inspiration for their own skylines; it is not coincidental that the term for rapid vertical densification is Manhattanization.

History has quickly been forgotten by selfish NIMBYs who have hijacked the city’s preservation processes, twisting them to prevent development rather than support architecture legitimately worthy of landmarking and preservation. This has resulted in exorbitant real estate prices, endangering the neighborhood dynamism that makes New York so vibrant and attractive to locals and tourists alike.

While the Municipal Arts Society may serve some decent purposes, the organization has recently taken to spreading images where gigantic orange blobs supplant the designs of future buildings – and then alleging that developers are the ones who are misinforming citizens. Though Extell hasn’t been forthcoming with designs for 217 West 57th Street, YIMBY has nevertheless revealed that tower’s design, along with all the others coming to the 57th Street corridor — each of which will offer a unique and contemporary contribution to the skyline, while also marking an end to the epoch of the mundane Midtown plateau.

At the ground level, NIMBYs have used similarly nefarious tactics to fight for nostalgia instead of common sense. While the demolition of Rizzoli’s former home at 31 West 57th Street was no great loss — and in fact, the store has already re-opened in a new location — Chickering Hall’s demolition just a few doors down was met with nary a peep from anyone besides YIMBY.

Perhaps more egregious than the orange blob tactics of the MAS or the rantings of ne’er-do-well cheerleaders like Gale Brewer is the effort by NIMBYs in Midtown East to kill plans for a 900-foot-tall residential tower at 428 East 58th Street, under the guise that it would not be affordable. This is particularly rich coming from opponents within a census block that already ranks within the top one percent of tracts across the country in terms of income.

The aforementioned anecdotes highlight the hypocrisy of a significant portion of the city’s aging population of Baby Boomers, who would rather entomb New York City in a sarcophagus of red tape than come to terms with the fact that things may be just as good as back when they were 25.

Despite the ill-advised protests against positive change, there are many bright spots. In fact, the Municipal Art Society’s old headquarters at 111 West 57th Street – known as the Steinway Building – is getting a full overhaul. Once decrepit and lacking air conditioning, the building will be beautifully restored, refurbished, and integrated into the new Steinway Tower, designed by SHoP Architects. While rich NIMBYs may be adept at lobbing orange blobs across the internet, it was ultimately the developer of a supertall that came to restore and save the MAS’ former headquarters.

If anything, 2016 should mark a firm end to the faux-outrage by people who think shadows don’t already exist over Central Park – or at least the end to any pretense of potential action.

217 West 57th Street – Rendering © 2016 New York YIMBY

217 West 57th Street, the tallest of this year’s supertall crop, is already several stories above street level. Once complete, the Nordstrom Tower, a.k.a. Central Park Tower, will rise 1,550 feet to its roof, easily clinching the title of the city’s tallest roof from the 1,397-foot-tall 432 Park Avenue.

220 Central Park South – Rendering © 2016 New York YIMBY

Across the street, 220 Central Park South is also nearly a dozen floors above street level, on its way to an eventual pinnacle 950 feet above the streets below.

111 West 57th Street – Rendering © 2016 New York YIMBY

Restoration work on the old Steinway Building is already underway, and foundations are now being laid for the aforementioned 111 West 57th Street. JDS’ tower will reach 1,428 feet into the air, and SHoP’s design will complement and enhance the existing structure, echoing the Art Deco accents of 1920s New York with a facade clad in terra cotta, wrapped in ribbons of bronze.

53 West 53rd Street – Rendering © 2016 New York YIMBY

A few blocks to the south, the best emblem of NIMBY futility is also set to begin rising nearly a decade after it was initially proposed. Amanda Burden’s infamous and ill-advised decision to chop the top 200 feet off of 53 West 53rd Street resulted in a total height of 1,050 feet, which means the tower will now rank far below the buildings along 57th Street. But at least the Jean Nouvel building is finally under construction, with foundation work well underway.

30 Hudson Yards – Rendering © 2016 New York YIMBY

To the west, the most drastic changes relative to the baseline are taking place across the Hudson Yards. Last year, 10 Hudson Yards topped-out 895 feet above street level, and this year, three of its companions will also begin to rise.

15 Hudson Yards – Rendering © 2016 New York YIMBY

35 Hudson Yards – Rendering © 2016 New York YIMBY

15 and 35 Hudson Yards will tower 915 and 1,005 feet tall, while the centerpiece of the Hudson Yards’ first phase – 30 Hudson Yards – will top-out 1,296 feet above Tenth Avenue.

1 Manhattan West – Rendering © 2016 New York YIMBY

One block to the east, the first of the Manhattan West office towers will also be going up this year, on the corner of Ninth Avenue and West 30th Street. There, 1 Manhattan West will soon stand 995 feet to its pinnacle, and while the design may verge on mundane, filling in the formerly gaping hole above the railways leading into Penn Station will be crucial as the surrounding neighborhood transforms into a hub for office workers, residents, and tourists alike.

175 Greenwich Street – Rendering © 2016 New York YIMBY

The sole Downtown tower on the list is 175 Greenwich Street, which is already more than halfway to its future 1,070-foot peak. Like the office giants of the Hudson Yards, Three World Trade Center, as it is more commonly known, will be similarly transformative to the surrounding neighborhood, with a major retail component that will further the Financial District’s rapid evolution into a destination for shopping of all sorts.

It’s easy for rich NIMBYs to criticize these buildings for any number of reasons, but taken in sum, the positive changes each of these projects will effect on New York City will be enormous. From the jobs relating to their construction to the people who will eventually work and live in these towers, the fiscal gain to the city will also be significant.

But besides their intrinsic value, the extrinsic impact on the skyline will be equally huge. One World Trade Center will no longer be so lonely, 432 Park’s visual impact will soon be balanced by similarly-sized companions, and 10 Hudson Yards will stand as the shortest sibling amongst a quartet of giants.

Whether the NIMBYs like it or not, 2016 will mark the turning point in Manhattan’s history when supertalls became the new normal. If the skyline is a forest, these towers are the equivalent of redwoods, signifying increasing maturity, and most importantly, an expansion of opportunity for all the little humans in the forest below.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

Remind me what multi-multi-million dollar super-luxe condos do for all the “little humans in the forest below”??

$$$$$ Property Tax

Sadly not so much:

http://www1.nyc.gov/site/hpd/developers/tax-incentives-421a.page

Over $1B in tax cuts for billionaires:

http://www.mas.org/urbanplanning/421a/

Overzealous “historic preservation” NIMBYs force out affordable housing, force developers to include parking garages, making units cost more. If local gov’t wants more new affordable housing, they should build more public parking garages to allow apts without included parking, and tear down lesser old bldgs that aren’t worth keeping. Cities should choose local landmarks that are worth preserving, not just any old bldg on the block.

I admire YIMBY’S courage in taking on the hypocrates and self serving snobs at the so called “Municipal Arts” Society. That organization has for years been more a tool for the gilded established class to protect their own hi rise views than an objective and constructive proponent of smart, progressive new archtecture. If MAC was as influential at the turn of the last century as it became toward the end of the last century we would have none of the iconic tower architecture now hailed around the world for its engineering and creative genius. MAC should stick to its dusty and cloistered ivy covered origins, limiting it’s comments to new construction at Yale and Harvard and rather let the new blood invigorate this City’s future.

Shame on the author of the following sentence in this article: “The aforementioned anecdotes highlight the hypocrisy of the city’s aging population of Baby Boomers, who would rather entomb New York City in a sarcophagus of red tape than come to terms with the fact that things may be just as good as back when they were 25.” To lump all people of a certain age into one group and describe them as he or she does here is not only demographically inaccurate, but also snide and small-minded. I am a “Baby Boomer” who is very supportive of the development of many supertall buildings, so how am I supposed to react to such an absurd claim? Now, it’s possible that the author intended to describe a subset for whom this description may be accurate. If that’s the case, however, then he or she needs to learn how to use commas–something that many Baby Boomers mastered long before this person began throwing sloppy language onto the page and thinking he or she was a writer or journalist.

That should have a qualifier, apologies!

It’s often difficult to tell if YIMBY is just playing naive in order to be provocative. Regardless of the answer to that question, what we do know is that in this article YIMBY talks about quantity and quality as though they are the same thing. The Empire State Building and the Woolworth Building were known around the world as two of the most beautiful towers ever designed. They follow architectural principles which modern neuro-testing show resonate with people: top, middle, bottom compositions; rhythms in the windows and parts of the building; punched windows that produce a contrast of light and shadow and a feeling of gravity being respected; harmonic proportions; pleasing materials; human-scaled on the street; city-scaled on the skyline; etc.

By contrast, most of the new towers look like shrink-wrapped origami miniatures blown up to a giant scale. What is distinctive about them is their size (YIMBY calls this “supertall” talking only about quantity.) They have a mechanistic repetition of a small number of elements that data shows people find visually boring; they are boring on the street and on the skyline; they rarely have any elements that give a human scale for people to relate to; etc. Of course YIMBY can say this is all elitist nonsense—but it’s not. We know that the average New Yorker agrees with the architectural critic who wrote in Architectural Record, “New York City is reaching a tipping point, architecturally. The city has the chance to go the way of London and Paris, where carefully chosen bits of contemporary architecture enliven an urban fabric that remains largely intact, or the way of Shanghai and Dubai, where relentless repetition of glass facades leads to a numbing sameness.”

Dubai and Shanghai have taller buildings than we have (quantity). We used to have better designs (quality). But now the same small group of architects design the same boring buildings around the world. There is no difference between the tower in Hong Kong and the tower in New York. Most of the time, they’re both bad.

Your first point could be countered with the argument that so many towers of such size means that fewer must be standouts. The ESB and the Chrysler were/are amazing but that’s also partially because they were the very first of their kind. Even traditionalist architects like Robert A.M. Stern draw significant criticism; no one is ever happy with designs when they first come out, but time tends to heal opinions.

I would not look to London or Paris as examples of exemplary urbanism. Both cities isolate immigrant groups in high-rise ghettos and suburban decay is now corroding into the city centers as you can gauge from the various headlines. New York City’s more integrated approach has benefited its citizens tremendously, and while it may not be perfect, it is miles better than the situation in either London or Paris.

RE: NYC vs. HK, both cities are part of a globalized economy extending to architecture and the fact that buildings may bear some similarities speaks to how New York-based architects like Cesar Pelli and Kohn Pedersen Fox are designing the tallest buildings in other cities around the globe in addition to their work here at home.

This is not necessarily NYC becoming more like the rest of the world — to the contrary, it’s that many cities in the rest of the world are becoming much more like New York.

I suppose it’s easy for a blogger who never once stepped inside Rizzoli Bookstore to dismiss its destruction as “no great loss,” but the atmosphere of the store and its sense of layered history was really quite unique. Despite great cost and the loss of veteran staff, Rizzoli was able to relocate to a new location downtown, but based on what we’ve heard from customers, the new store leaves much to be desired.

The campaign to save 31 West 57th Street was focused on saving the 1919 Sohmer Piano Showroom building. Since LPC cannot regulate use, saving the bookstore was a secondary concern. Both 29 and 31 warranted landmark designation, but of the two buildings, 31 West 57th Street had greater merit. The Sohmer Company was more closely associated with the history of New York City—it was the first piano company to move to 57th Street and its factory in Queens and 22nd Street offices are already landmarked. Ampico only occupied 29 W 57th Street for four years before relocating to Fifth Avenue, and unlike Sohmer, none of the original interior showrooms survived.

Community Board Five supported landmark designation for both buildings, but only 31 West 57th Street was cited as a priority for designation in LPC’s internal Midtown West Survey in 1979. An early study prepared by PKSB in 2009 for Vornado showed plans for preserving the facades of 31 and 33 but not 29 West 57th Street. Stern’s New York 1930 dismissed the sculptural ornamentation on Chickering Hall as “stodgy” and his evaluation was cited in an assessment report commissioned by LPC from Mary Dierickx. While Cross & Cross was a distinguished architectural firm, many of their office buildings appear to be unpopular with LPC staff for whatever reason—LPC has steadfastly refused to calendar Tiffany’s and the Postum building.

Now, if Mr. Fedak were so concerned about the fate of 29 West 57th St, he could have petitioned (as we did) LPC to calendar the building. Yet, as we know from information obtained through a FOIL request, Mr. Fedak couldn’t be bothered to submit a single letter or email requesting its designation.

The campaign focused solely on Rizzoli retaining its space and the decor within. The building itself was a sideshow. And evidently your letters to the LPC were a waste of time so why cite them as something noble or useful?

In any case, there were most definitely no demonstrations as the businesses occupying the retail of 29 W 57th closed. And I did not say I necessarily supported landmarking Chickering Hall, either. There are other means of preservation.

Incentivizing the integration of historic architecture in new construction is what should actually be encouraged, with FAR bonuses for developers who take them time to integrate the most noteworthy parts of the past into our future.

The campaign was focused on far more than Rizzoli retaining its lease. As betrayed by your previous comments, you’re as ill-informed about the goals and methods of preservation campaigns as you were the significance of these particular buildings. It’s one thing to be a cheerleader for supertalls, it’s quite another to project motives based on nostalgia onto people you’ve never met.

Good article. But is that an accurate rendering of 220 Central Park? Where is it coming from? I’ve not seen the top depicted like that. Not a fan at all. Diminishes an otherwise nice building.

Nikolai, any idea why 15 Hudson lost is trademark “ropeknot”? It looks kinda…boring now.

YIMBY is an interesting destination to get an overview of changes coming all of the city and increasingly beyond. As such, it performs a valuable service and fills a heretofore empty niche. As a lifelong New Yorker (albeit with stints abroad and on the West Coast), I feel it should be possible to both embrace change and preservation – they need not be mutually exclusive. I can honestly say that 95% of the time or maybe more I have been pleased or relieved to see on YIMBY that proposals for new development are mainly affecting sites that are not especially aesthetic, well designed, or even (in the case of empty lots) built upon.

That there is a corridor of supertall buildings being created in the 57th Street corridor does not especially trouble me – that wasn’t much of a neighborhood anyway. The same goes for the Far West Side at Hudson Yards and the Financial District. The skyscraper is in New York’s DNA, but it seems to me that it would be appropriate to guide such supertall development into corridors and sightlines with an eye toward “curating” (to use a much overused word) an attractive skyline and views from throughout the city. I fear that the pace of supertall construction is starting to stray throughout the city in a willy-nilly fashion that may start looking more like a sprawl of skyscrapers rather than an organic, cohesive whole.

None of the buildings pictured in this article seem terribly distinctive or especially beautiful. Those buildings could just as easily be in Shanghai or Seoul. It seems doubtful that they will add much to their communities at street level, and they surely will do nothing to increase the supply of affordable housing. I don’t understand why every new skyscraper seems to have to be nothing but steel and glass – especially in a city where much of the fabric if limestone and masonry. One Vanderbilt is a case in point – it would have been aesthetically preferable had this proposed supertall not involved a super reflective glassy façade. The glassy supertalls are visually boring and don’t make New York feel or look more uniquely itself.

Being pro-development is one thing, but there is no reason to cast aspersions on the Municipal Arts Society or historic preservation. It’s not fair to cast every critic of a new development proposal as an elitist or an “old” person clouded by nostalgia.

Much of the anti-NIMBY criticism in the above article seems to repeat REBNY’s anti-landmarks shibboleths. In general, landmarking has done much to make NYC a better, more livable place for all of its citizens, not just the 1%. In poorer neighborhoods, like Fort Greene or Bedford Stuyvesant, landmarking helped stabilize home values at the time and set the stage for the renaissance of those neighborhoods in the 90s and 00s – much to the benefit of the African-American homeowners there who are now realizing increased values of those homes as they sell and retire. In Manhattan, landmarked neighborhoods preserved a human-oriented streetscape in places like Greenwich Village and SoHo, and this very streetscape is much of what people like about these neighborhoods. Without landmarking, SoHo would never have become the shopping destination it is today.

That said, there is no question that it has become commonplace for New Yorkers to appeal to the landmarks board in order to control or manage the rampant change around them. This is so because there are very few other mechanisms in this city for a community to gain leverage over proposed changes its built environment given the enormous gobs of money at the disposal of the developers and the unfortunate way they seem to buy our local politicians. Zoning and environmental review which could serve as a brake on development allowing for community input are regularly evaded – even now, the mayor is attempting to evade a full environmental review (not to mention rightful input from the community boards) for his wholesale rezoning plan (barely a decade after a citywide rezoning that was based on a great deal of community input) which a plurality of New York residents see as little more than a favor to developers couched in the feel good language of “progressivism.”

That leaves landmarking as one of the few ways for citizens and communities to leverage some control over their built environment. However, as the Rizzoli case proved, the landmarks board does not landmark buildings at the eleventh hour to merely control development. In fact, few such appeals are ever successful, and in the Rizzoli case, landmarks quickly decided there was no merit. It is also true that landmarks typically prefers not create an historic district if the majority of affected property owners are opposed. The fact that there are as many historic districts in the city as there are is testament of how warmly embraced historic preservation has been in many NYC communities. And even historic districts are open to new development (cf. St. Vincent’s Hospital) and constantly changing.

It seems as if for REBNY and its enablers, there has never a building they wouldn’t like to see torn down, and the reasons to oppose preservation seem to shift like a kaleidoscope. A decade ago, they liked to say preservation was bad because it was cheaper and more efficient to build new rather than repurpose or restore. Now they are saying that it kills jobs and caused the affordability crisis. But let’s be honest, repurposing a historic structure uses construction labor just as a new development does, and no one could say with a straight face that new development in NYC is in any way endangered. As for the affordability crisis, that’s baked in to the city’s DNA as well and is far older than the landmarks board – c.f. Scarcity by Design: The Legacy of New York City’s Housing Policies, by Peter Salins and Gerard Mildner.

I wonder what we would see if there were a true an honest accounting of the costs and benefits of the new developments going up in the city, once various tax breaks and abatements are factored in as well as effects on the local environment both natural and manmade (subway capacity, surrounding rents, etc.).

Well said. However, as you know, the case for landmarking the Rizzoli-Sohmer building was not rooted in curtailing development. Support for landmarking these buildings preceded the news of their demolition. The Landmarks Preservation Commission declined to calendar these properties based on purely political calculations–not on merit.

Thoughtful, articulate letter by Klaus Kirschbaum. Thank you, Mr. Kirshbaum, for posting and illuminating in a clear, reasoned and concise manner, the issue of preservation and how it relates to smart growth. Not as an enemy of development as Mr. Fedak inferred.

I enjoy the city wide focus of YIMBY and previews of renderings, but the tone of this last piece gives me pause. Criticism can be constructive. This just seemed punitive and does damage to the professional reputation of this blog and REBNY.

Intelligent responses to the attack on preservation. I have never understood why a city such as NY cannot find the common ground to enable preservationists and developers to work hand in hand and preserve our streetscapes while still encouraging much needed development? Rizzoli’s was a landmark not just for architectural merit. It’s fine interior ceiling plasterwork was exceptional and the luxe interior fittings purposely rich with detail and with a human scale appropriate for an establishment retailing our fast disappearing book culture. Chickering Hall’s facade was richly detailed but was uniquely positioned to play wonderous reflective tricks against the curved glass facade of its highrise neighbor. The textures, scale and materials of older NY buildings interacting and playing with later construction is an unexpected and unique surprise that is fast disappearing from this city with the continued saturation of endless glass facades that de-humanize the streetscape and city experience at sidewalk level. 57th Street had that scale when the Rizzoli block featured both Chickering Hall and a giant sloping swath of reflective glass as it’s neighbor. Now the Gilded Age Vanderbilt family townhouse will be surrounded by scaleless glass and steel behemoths, forcing pedestrians to scurry along, forever losing the wonder that this street once had. Rows of glass facades, devoid of pedestrian level amenities do not make a city. We are all the poorer for it. NYC should be more proactive in adaptive re-use and incorporating older buildings and even important facades into new construction projects. One can’t rely on the LPC to rescue all noteworthy buildings at the last hour, they rarely do. There must be a desire to see our streetscapes preserved while welcoming change and development. Both can coexist. it is too late for 57th street unfortunately.

Thank you Mr Kirschbaum for your well-thought out response. I work in building maintenance and remind everyone that each of these new buildings, besides employing many in construction, also employ others like me to clean them. These are working- and middle-class jobs like we used to have in the factories (I was a glass blower) but as all of you know those manufacturing jobs and their union wages disappeared. Building staffing and maintenance employ many thousands of us. We are not the super rich or even mildly successful by 2016 standards perhaps, but we earn a living wage and support our families and populate the public schools and live in the boroughs (the Bronx, in my case) and shop our local shopping strips. We are part of the city also in an important service capacity. So it’s a trade-off: on the one hand much of the old and not-so-old is torn down but much new (perhaps not that architecturally distinguished) is put up. People like me and the many I work with get living wage jobs. Thank you to those who employ us. We will continue to clean, maintain, and secure your buildings and keep their tenants safe.

I grew up in NYC I’ve been living in San Diego the past 30 years. New York will always be my hometown and the greatest city on earth. Build it to the Heavens. No place on earth gives me the excitement i feel seeing the New York skyline grow as I approach the greatest place on earth. New York can never be too big. Some day I want to see the skyline from the San Diego beaches !!!