Mayor Bill de Blasio has set his sights on upzoning 15 neighborhoods as part of his affordable housing plan. Now his housing and planning teams must choose which neighborhoods are best suited for population growth, and one of the most important factors for them to consider is transit access – not only a neighborhood’s proximity to transit, but also whether an influx of new residents would overwhelm and overcrowd the system.

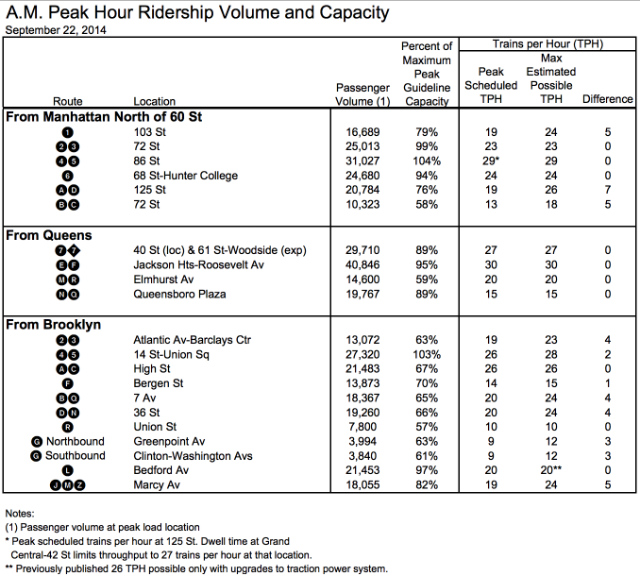

Most New Yorkers will tell you that the subways are crowded, very crowded, during the morning and evening rush. But it turns out that many neighborhoods across the city – mostly in Brooklyn – could handle a lot more riders. In fact, according to data provided to YIMBY by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, all but two subway lines in Brooklyn could handle significantly more commuters today during rush hour: the 4/5 and L trains.

Crowding is more severe in much of Queens, the Bronx, and Upper Manhattan, where chokepoints lead to stuffed trains up and down the line, limiting opportunities for new housing development. Fortunately for the mayor, whose affordable housing plan hinges on robust development activity, the MTA is making improvements that will help clear up the city’s most congested subway lines even as the city continues to grow.

By the end of 2016, the first phase of the Second Avenue subway should finally begin carrying passengers, relieving pressure on the maxed-out express trains on the Lexington Avenue line. The MTA could potentially begin construction on the second phase by 2019, extending the line northward to 125th Street in East Harlem.

The transit authority is also making improvements on existing subway lines that will allow it to run more trains per hour. It recently installed a computer-based control system on the L train and it is wrapping up similar improvements for the 7 train. If all goes according to plan, the Sixth Avenue and Queens Boulevard lines will be next, clearing up bottlenecks in Queens and on the Lower East Side.

But with a $15 billion funding gap for the MTA’s next five-year capital program, Governor Cuomo has said that he would like the MTA to pare back its spending – which, given his seeming lack of interest in cutting construction costs, likely means eliminating projects. This could cool the development climate in the years to come as crowding worsens on the most heavily-used portions of the system.

Still, the city has some options if the state makes the unwise decision to cancel essential projects. As-is, Brooklyn’s existing transit infrastructure could handle far more riders, and the de Blasio administration could tap into the incredible energy of the borough’s resurgence to lay the groundwork for a building boom.

In northern and central Brooklyn, there is tremendous untapped capacity along the J/M/Z line, which straddles the border between Bushwick and Bedford-Stuyvestant, two of the city’s most rapidly transforming neighborhoods. The line is at 82 percent capacity as it approaches Marcy Avenue, but the MTA has the ability to run up to five more trains per hour if ridership demands it.

Even the L train, currently at 97 percent capacity, could potentially accommodate a lot more riders – as long as the MTA is able to upgrade the electrical infrastructure that propels trains along the line. As part of the upcoming capital plan, the MTA would build three new electric substations in Brooklyn that — in addition to new rolling stock — would allow up to six more L trains to run per hour, and take full advantage of its new computer-based train control system.

The MTA also plans to improve access to the L’s Bedford Avenue station in Williamsburg and the First Avenue station in Manhattan, though an MTA spokesman wouldn’t go into detail beyond the capital plan’s mention of elevators and handicapped accessibility. (The obvious fix for the First Avenue station, though, would be an additional entrance towards Avenue A.)

Incidentally, both the L train and the J/M/Z head out to East New York, which is first in line for the de Blasio administration’s 15 neighborhood upzonings. Given the tremendous untapped capacity along both these lines, de Blasio’s housing team can go big in East New York and not strain Brooklyn’s transit infrastructure.

There is also plenty of unused capacity in southern Brooklyn, where trains running on the B/Q and the D/N lines are only two-thirds full as they head into Manhattan during the morning rush. The MTA could also run up to four more trains per hour on each line, if ridership demanded it. Even the much-maligned F train is only at 70 percent capacity as it travels through Bergen Street.

The worst crowding in Brooklyn occurs on the 4/5 trains as they head into lower Manhattan, and while the MTA could technically run two more trains per hour, crowding further up the line makes this impractical. The 2/3 trains, on the other hand, are extremely under-utilized in Brooklyn, likely due to the West Side’s lower job density and the fact that they run on the slower local tracks through Brooklyn.

Of course crowding is much worse whenever there are significant delays, and all definitions of crowding are somewhat arbitrary – nothing in New York City would be particularly crowded by Tokyo standards, for example. The MTA defines crowding as what you see on the downtown numbered express trains in the morning from the Upper East and West Sides, where trains are at 104 percent capacity on the 4/5 and 99 percent on the 2/3 trains.

This crowding affects riders in Upper Manhattan and the Bronx and limits prospects for significant new housing development, but there are still some neighborhoods north of Midtown where the subway system is well below capacity. The A/B/C/D trains in Upper Manhattan and up the Grand Concourse in the Bronx all have a lot of room, and the MTA could also run several more trains per hour along these lines. The 1 train has additional capacity as well, as long as riders are content to ride the local train all the way to Midtown.

In Queens there is extra room on the local M/R trains running along Queens Boulevard, but many riders want to switch to the crowded express trains. Still, any development along local stops between Queens Plaza and Jackson Heights-Roosevelt Avenue would not strain the express trains, since there is no speed advantage to switching from the local along that stretch.

To accommodate more development in Queens, the city could also explore ways to better utilize the borough’s Long Island Rail Road infrastructure. More riders would likely take the LIRR if fares were more comparable to the subway and service was more frequent (both of which would be easier to pull off if ticket collection and on board staffing levels were more subway-like).

The problem that will remain the most difficult is crowding on the Lexington Avenue line – a full Second Avenue subway into Midtown and down to the Financial District is still a long way off, if it ever comes to fruition. One way to approach this issue would be to plan for job growth elsewhere.

This isn’t to say the city should abandon the tony east side of Midtown, but planners could also encourage job growth on Manhattan’s west side, where the Sixth, Seventh and Eighth Avenue lines all have extra capacity below 42nd Street. While the city has been subsidizing and zoning for office space in Midtown West for decades, to varying degrees of success, the area around the Meatpacking District has both the subway capacity and the demand to sustain office development that still pays full property tax bills.

Meanwhile, the de Blasio administration has a lot of good options when it comes to neighborhoods that can handle more riders. Only a few areas are overcrowded, and on many of these lines, help is on the way. The biggest challenge for the de Blasio administration isn’t transit capacity, but convincing New Yorkers that their commutes are not quite as crowded as they make them out to be.

Talk about this topic on the YIMBY Forums

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews