Literacy is the cornerstone of modern society, and libraries stand as the foundations of thriving communities. While Long Island City’s rebirth manifests itself through its skyrocketing skyline, its most significant public building steadily rises at the waterfront. The Steven Holl-designed Hunters Point Library will join the iconic gantries and the Pepsi-Cola Sign to form the borough’s new public face, while becoming a new focal point for the rapidly growing community.

The 2010 census counted 68,117 residents within Long Island City. Since then, Queens’s westernmost neighborhood has added thousands of new residential units, with over ten thousand more on the way. But even prior to its meteoric growth, LIC has been in dire need of libraries. Its most significant branch sits in a relatively new building at 38th Avenue, yet its presence is diminished by its location within an industrial no man’s land in Ravenswood, on the fringe between Long Island City and Astoria. Another one is tucked away in a nondescript building within the deep interior of the Queensbridge Houses, the largest housing project in the country.

The entire portion of the neighborhood south of the Queensboro Bridge/Queens Boulevard, which includes Hunters Point, Blissville, Court Square, and half of Queens Plaza, is serviced by just one branch. Its Court Square location puts it at the center of the borough’s civic core. Unfortunately, the branch is underwhelming almost to the point of anonymity, tucked away in the rear annex of One Court Square, at a mid-block site on the sparsely traveled 45th Avenue.

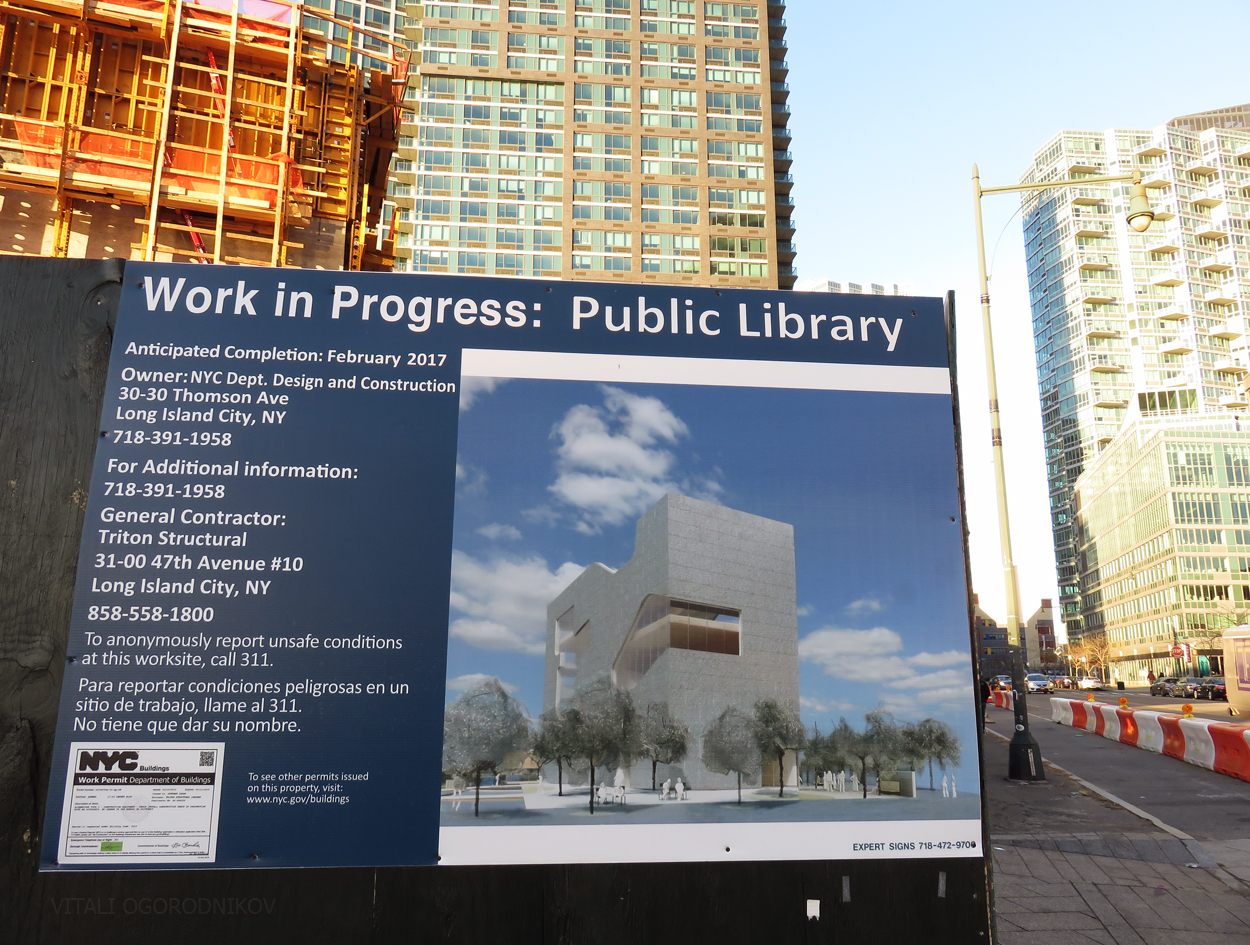

The new branch at 47-40 Center Boulevard may be removed from the district’s resurgent core around Court Square, but its waterfront location opposite the United Nations and Midtown Manhattan, as well as its novel design, will make it into the iconic facility that will represent both the neighborhood and Queens as a whole. Just as importantly, its function will service the decidedly residential, family-friendly Hunters Point neighborhood, where a series of new residential towers complement the blocks of densely packed rowhomes farther inland.

Source: Steven Holl Architects

The library’s site has been the neighborhood’s focal point for quite a while. Long Island City had been a busy industrial hub since the 19th century. In 1925, two gantries opened at the western terminus of a freight rail branch that serviced the borough’s manufacturing district. The gate-like, steel structures transferred goods on to Manhattan-bound floats. In 1938, Pepsi-Cola opened a bottling plant next to the gantries and addressed the business hub across the river with a now iconic 60-foot-tall, neon-lit sign. After World War II, the neighborhood’s industry went into decline. By the end of the 20th century, it was but a shadow of its former glory.

But as factories crumbled along the once-busy streets, the first seeds of the neighborhood’s renaissance were planted. In 1990, the 658-foot-tall Citibank Building at One Court Square introduced density and modernity to the Court Square district. The waterfront made a similar statement six years later, when the 42-story Citylights condominium building brought 522 residences next to the bottling plant. The extra wide 48th Avenue, which once carried rail freight to the gantries, became a green boulevard. Residents were encouraged to move to the post-industrial periphery via steep discounts. In 1999, Pepsi-Cola shut down and demolished its plant. Thanks to community effort, the iconic sign was restored and placed onto a green promenade in front of TF Cornerstone’s East Coast LIC apartment complex, which stretches to the north. The industrial relics became namesake to Gantry Plaza State Park, which serves the new residential community as effectively as the gantries served the industrial clients of yesteryear. In the meanwhile, development continues to the south, where Hunters Point South transforms marshy, post-industrial lots into affordable housing and parkland.

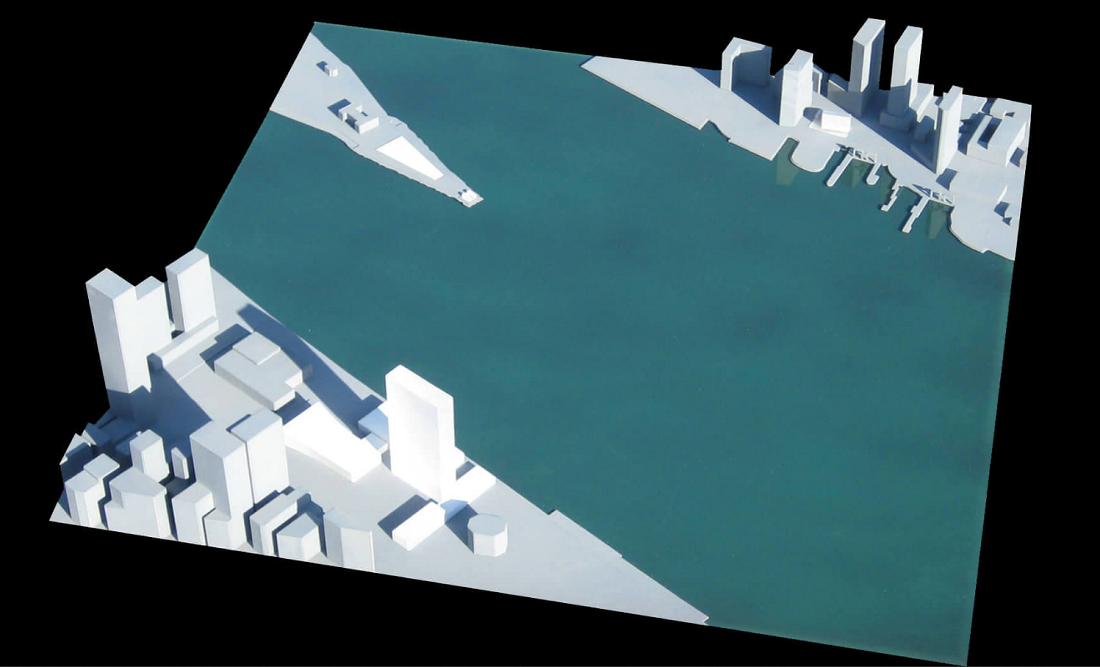

The future library frames the northern edge of the park’s gantry-bound central plaza. Given its centrally located site facing Manhattan, the facility must serve not only as a beacon to complement the industrial landmarks, but also as a gathering space for the growing community. Steven Holl and his fellow architects envisioned the project as a sculpted rectangle, which measures 168-feet-long, 40-feet-wide, and 109-feet-high. The structure is oriented along the north-south axis, offsetting it from the prevailing street grid, which is slightly slanted in relation to cardinal directions.

The library draws inspiration from its greater context across the river. It forms an isosceles triangle with the United Nations Secretariat Building to the west, as well the Four Freedoms Park, which marks the southern tip of Roosevelt Island as a memorial to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, to the northwest.

Library alignment with the United Nations and the Four Freedoms Park memorial. Source: Steven Holl Architects

On the outside, the 21,500-square-foot library appears as boxy as its landmark counterparts across the water, yet the interiors flow in a decidedly fluid manner, zig-zagging upwards to the outdoor rooftop auditorium that faces Manhattan via an open wedge carved from the rectangular form. The cutout follows the façade apertures, which, in contrast to the rectangular exterior, flow as soft openings that present library users with dynamic, sculpted views of the city beyond the concrete walls. The most notable feature within the river-facing west façade is the grand “Manhattan stair,” where bookshelves and desks diagonally cascade next to the expansive, city-facing window. Another cutout features a “view terrace” with outdoor access.

Source: Steven Holl Architects

Source: Steven Holl Architects

On the east façade, three large apertures open into the children, teen, and adult areas, respectively. The architects optimized interior space by concentrating HVAC equipment entirely within the basement, as opposed to its more traditional setting at the top level.

The gardens at the threshold connect the park on the outside to the readers within. A reflecting pool of recycled water fronts the building in the west. The “courtyard” within the east side interior, sheltered by the residential high-rises to the north and east, houses a reading garden, where ginko trees would sprout from a gravel surface. The space would be enclosed with a “garden wall” facing the street, as well as a small building containing office space and public toilets to the north.

Source: Steven Holl Architects

The concept received high praise from architecture critics, winning the “2010 Award for Excellence in Design” in 2011. James Murdock of the Architectural Record called it a “jewel in the crown” of the area’s development and praised the bold departure from the traditional “Carnegie library archetype.” Nicolai Ouroussoff of the New York Times heaped similar praise for reinventing the library image, claiming that its interaction with the cityscape across the river “is not about escaping this world but transforming it into something more poetic,” where “the views remind us that the intellectual exchange of a library is part of a bigger collective enterprise.” Architect Katie Gerfen praised the building’s green features, which include the recycled foamed-aluminum exterior rainscreen, geothermal heating, and photovoltaic cells on the rooftop.

Unfortunately, as happens all too often when starchitecture meets the public realm, budget limitations resulted in design revisions. Geothermal heating was eliminated, and the metal façade was substituted with silver paint over concrete, meant to imitate a metallic sheen.

The library is on track for its 2017 completion. In the meanwhile, Hunters Point residents have the use of a mobile library parked in front of the construction site.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews