What is Brooklyn? For many, the borough is associated with new buildings populated with young professionals fleeing Manhattan, where the cost of living rises as high as the skyscrapers. Some prefer to dismiss them as silver-spoon suburban transplants wishing to emulate some fantasy starving artist lifestyle, which they would assert is long-gone from the borough. Others would disagree, pointing at the “authentic Bohemians” living in rundown, graffiti-covered, and sometimes illegally-run lofts on the fringes of industrial districts, not yet touched by true gentrification. In contrast to another stereotype, which presumes that manufacturing has also left the borough, these pockets of industry still teem with activity, whether in dusty cement-mixing lots, in auto shops that clog the sidewalks in front of them with rides-in-progress, or in manufacturing plants where they are rightfully entitled to slap a “Made in Brooklyn” label onto their wares.

Either of the above would be a correct answer to the initial question, as well as a variety of other options, ranging from inner city ‘hoods dotted with housing projects, to immigrant enclaves and their familiar-yet-distant flavors and lifestyles, to quiet, tree-lined rowhouse streets that seem frozen in time as years flow by. Slate Property Group’s 83 Bushwick Place is wrapping up construction at a rare junction where every typology listed above comes together in the space of a few blocks.

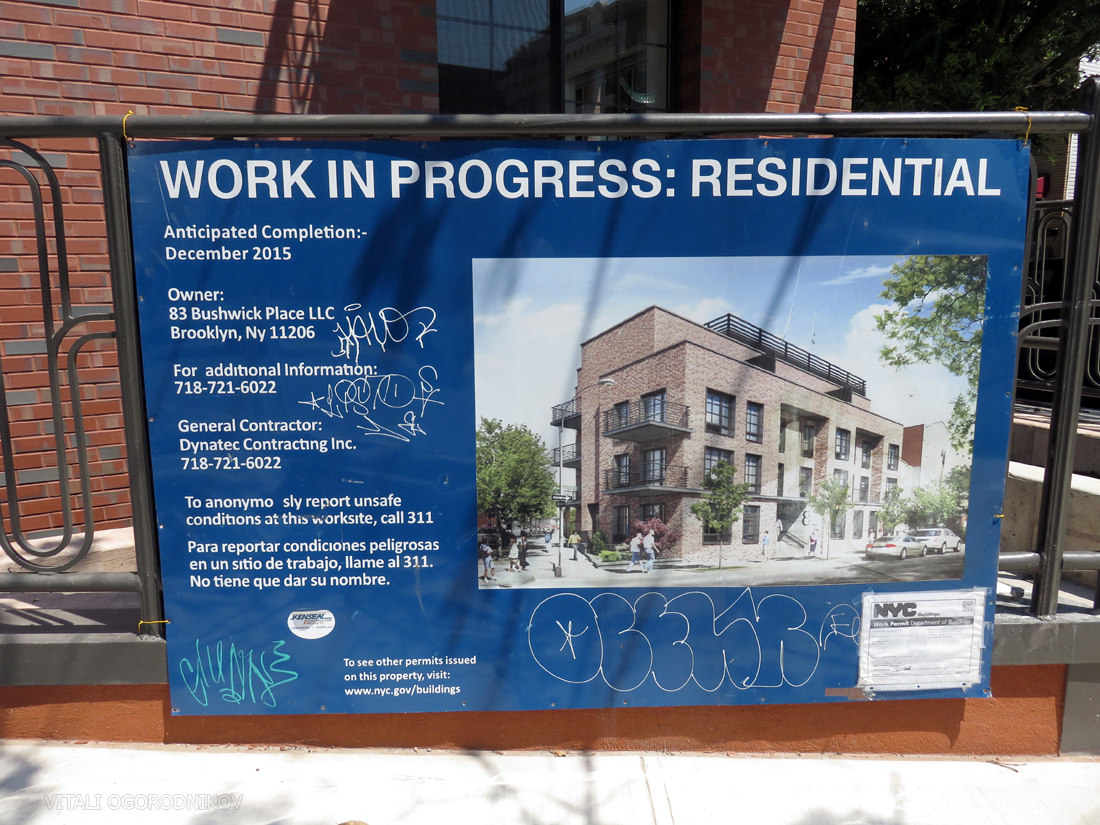

The four-story, brick-faced building rises from a trapezoidal, 5,573-square-foot lot. It sits at the intersection of Boerum Street and Bushwick Place, where the curving, one-way street starts its three-block-long run.

Its 20 rental apartments span 13,191 square feet of the 19,516-square-foot structure, translating into 660 square feet per average unit. Nine parking spaces will be accessible via a ramp at Bushwick Place.

The building sits within the M1-1 manufacturing zoning district, across the street from the R6 residential zone encompassing East Williamsburg, forcing its developers to apply for special zoning easements.

Prior to construction, the fenced-off dirt lot was occasionally used for parking. The general contractor, Dynatec Contracting Inc, broke ground on the project around early 2015, topping out the building by fall. The structure was largely complete by the beginning of this year, with windows and interior finishes installed throughout spring.

During the design stage, Aufgang Architects faced an unusually diverse urban context. To the south and east, Boerum Street sports traditional, two-story rowhomes, clad in vinyl siding emblematic of Williamsburg. The North Brooklyn Industrial Business Zone starts half a block north. There, despite encroaching construction and gentrification from all sides, Johnson Avenue still bustles with constant daytime congestion generated by the low-slung, sprawling warehouses, and small-scale industry. Though Google Maps may claim otherwise, the building sits at the northern fringe of Bushwick proper. A short block west, multi-story, mid-century housing projects lining Bushwick Avenue run into the gentrified blocks of East Williamsburg to the north, separated from one another by Johnson Avenue. McKibbin Street runs one block south, lined with pre-war loft buildings. Their mural-painted walls contain crammed artist quarters, studios, and hostels, some of which have recently been discovered as being operated illegally. The new building’s roster of unorthodox neighbors is rounded off with a hulking but ornate MTA facility standing across the street to the southwest. It services the L train, which turns from north to east directly beneath.

As dictated by zoning and the project program, the building boasts just the right size in order to act as a transition piece between the variety of surrounding scales and typologies. Still, its bulk was broken down into smaller visual components to avoid overwhelming its rowhouse context. Its mass is composed of four rectangular forms, staggered at a diagonal that follows the angled Bushwick Place to the west. The zig-zagging west facade mirrors that of 246 Johnson Avenue, which rises across the street. Together, the two projects introduce a new, shared visual language to the block.

The staggered rectangles break down the building mass without making the composition look disjointed, while saving time and money during the construction process (it is generally cheaper and easier to design and build at right angles than otherwise).

To prevent the southernmost module, which overlooks Boerum Street, from reading as a single, massive slab, the architects punctuated its form with two large niches.

In terms of aesthetics, the architects embraced the neo-industrial look. The style relies on textured brick and dark metal accents, and is particularly popular with small- to medium-scale residences in districts with industrial heritage. It has been successfully employed in projects ranging from Robert A.M. Stern’s Abington House by the High Line, to John Fotiadis’ 42-14 Crescent Street in Long Island City. The building’s pleasantly textured, red and gray brick softens the otherwise plain facade, which eschews all decoration aside from metal trim above the first floor, along the cornices, and along the balconies. The casement windows are sunken within bays that give a sense of depth to the facade. The slightly protruding, thin sills are a nice touch that distracts the eye from the HVAC grills below, although the windows are strangely missing even a basic lintel. Even a simple horizontal element capping each windows would have gone a long way on the the traditionalist but bare facade.

The weakest point of the composition is the tall blank wall that makes up the four-story central module. The eye is inevitably drawn to this centrally-located element, which looms over the three-story portion along Boerum, making the building appear bulkier than it actually is. Thankfully, it is prevented from being overpowering through the use of the pleasantly textured brick that is utilized throughout the project. The best part of the design is arguably the main entrance at Boerum. Its niche is clad in wooden planks, capped by the dark metal rail that runs above the ground floor.

As it often happens, even technical structures from the pre-war era were built with dignity and grace. The MTA maintenance building on the south side of Boerum is the most architecturally significant structure on the block, and we are happy that the architects of 83 Bushwick Place matched its red brick. Of course, the maintenance structure also signifies the proximity of the subway, as the Montrose Av station of the L train sits just 750 feet away from the main entrance, putting future residents within fifteen minutes of Manhattan. Though the commuters would have to deal with the headaches stemming from the impending years-long L train maintenance shutdown, some consolation may come from the Citi Bike station that is located across the street from the subway stop.

The area is undergoing one of the most dramatic transformations in the city. Over 50 projects are underway within a one-mile radius of 83 Bushwick Place. The neighborhood, recently referred to as Morganstown thanks to its proximity to the Morgan Ave station of the L train, forms the latest patch on the neighborhood tapestry of that makes up one of the most culturally diverse cities on Earth.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews