The New York City landmarks law was signed 50 years ago this year. So, what better time to talk about some of its successes? Plenty of great structures, such as the Empire State Building, completed in 1931 as a multi-tenant office building, are easy to keep relevant and functioning. Others, however, become obsolete and can no longer perform their originally intended purpose. That’s where adaptive reuse comes in. If you haven’t heard the term, it’s when an old structure is adapted for a new use. It’s often how we are saving our great city.

Recently, the chair of the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) joined six of the city’s top architects to discuss the topic of adaptive reuse at an event called “Preservation through Transformation” at the AIA Center for Architecture on LaGuardia Place in Greenwich Village. The LPC Chair reviewed many successes and the architects then discussed their current projects.

“We all know the overwhelming positive impacts of historic preservation. However, historic buildings, despite their visual, aesthetic, and symbolic merits, may pose challenges in modern day and evolving needs,” LPC Chair Meenakshi Srinivasan said. “Obvious conflicts may arise as a result of age, structure, and function, particularly with changing lifestyles, improved standards, and the programs and uses in an ever-changing market. The old – whether it’s buildings, structures, or spaces – has resulted in some of the most recognizable places in the world. Historic buildings are one aspect of our heritage.”

“Adaptive reuse has become a critical tool to promote preservation along with economic viability of buildings and vitality of neighborhoods and districts.”

Srinivasan pointed to one shining foreign example of adaptive reuse: the Louvre in Paris. It was a fortress and a palace before becoming the glorious museum we love today. It’s one of those places you need a list for. Top tip: The “Mona Lisa” gets big crowds, but is fairly small. The significantly larger “Coronation of Napolean” in the room behind it is much more impressive and gets far smaller crowds.

Another great Paris example, though not one mentioned at the talk, is the Musée d’Orsay, housed in a former train station that also housed a hotel back in its rail days.

What are the benefits of adaptive reuse?

“This tool effectively preserves neglected or obsolete historic resources – that might otherwise be lost and demolished – for future generations. It promotes good sustainability practices by conserving our limited environmental resources,” Srinivasan said. “It strengthens and revitalizes neighborhoods as real estate markets shift and original uses are replaced with new uses. And addresses our emotional and psychological needs for familiarity and continuity in our growing communities.”

Even in New York City, “the concept of reusing buildings is hardly a new idea,” she said.

“Historically, buildings were repurposed for uses that were compatible with the original form. Often, these buildings had a strong connection to the community, such as houses of worship and civic institutions and industrial and commercial buildings.”

The Town and Village Synagogue. Photo by Violette79/Flickr

The Town and Village Synagogue at 334 East 14th Street was built between 1866 and 1869 and started its life as the First German Baptist Church. Then in 1926, the space was taken over by the Ukrainian Autocephalic Church of St. Volodymyr. In 1962, it was sold to Congregation Tifereth Israel. “In fact, its layered changes reflecting the East Village’s cultural and social history are part of the reason for its landmark designation in 2014.”

Built in 1800 (according to its designation report), the Lorillard Snuff Mill in the Bronx was exactly that, a tobacco manufacturing building. Eventually, it was encompassed by the New York Botanical Garden. Srinivasan said it became a tea room in the 1950s. Still on the grounds of the garden, it is now a catering hall known as the Stone Mill.

MacDougal Alley. Photo by Wally Gobetz/Flickr.

“Many types of structures have adapted for residential use throughout New York, responding to the demand for new housing in growing communities,” Srinivasan said. She pointed to MacDougal Alley, which used to be a row of stables just off MacDougal Street, between Washington Square North and West 8th Street. In 1907, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, who would found the Whitney Museum of American Art, had a studio there. In the 1920s, with horse-drawn transportation becoming less prevalent, residential use came to the small street.

The Jefferson Market Courthouse, at 425 Sixth Avenue, was built in the late 1800s by Frederick Clarke Withers, partner of Central Park co-designer Calvert Vaux. It was the first judicial courthouse to serve Greenwich Village, but that use was discontinued in 1945. “In the early 60s, in the face of demolition and a maelstrom of opposition, the New York Public Library stepped in to convert and adaptively reuse this building as a library,” Srinivasan said. Giorgio Cavaglieri, an early pioneer in adaptive reuse design, was commissioned for the project.

“Along with the conversion of Astor Library into the Public Theater, [it] reflected a different trend,” Srinivasan said. “That of not simply changing the occupancy of buildings, but planning careful interventions and alterations to make historic buildings suitable for new use. This set the stage for the creative and unexpected adaptive reuse projects to come.”

Following the tragic destruction of sites like the original Penn Station and the Brokaw Mansion, the landmarks law was signed by Mayor Robert F. Wagner in 1965. It empowered the Landmarks Preservation Commission to designate landmarks and historic districts in order to safeguard “buildings and places that represent New York City’s cultural, social, economic, political, and architectural history,” according to the commission’s website.

Cases like MacDougal Alley and the Town and Village Synagogue are examples of when the city got lucky, but the landmarks law ushered in a new wave of legal protection for the city’s historic sites. Once a site is designated a landmark, any alteration or demolition has to be approved by the commission. The same goes for alterations, demolitions, and new construction in a designated historic district.

“The agency’s contribution to the concept of adaptive reuse has been to establish a road map on how to accommodate a wider range of uses without demolition of the historic buildings and by allowing significant changes without compromising the historic character,” Srinivasan said. “These buildings often have great presence in their communities due to their central location, as well as their style, scale, and level of ornament.”

“While adaptive reuse of these buildings raised design challenges, they offered unique benefits for those very same reasons. In fact, harnessing these so-called constraints into an opportunity has often paid off in the long run.”

One category of structure that the LPC has helped to keep as a relevant part of the community is religious.

“Societal shifts in religious practices have resulted in diminishing congregations and funding and sometimes decades of deferred maintenance, Srinivasan said. “This, coupled with often complex architectural forms and limited square footage, make designated houses of worship uniquely vulnerable to market pressures. However, we have found them surprising candidates for reuse in a manner that can promote economic development, provide housing, and maintain the building’s relevance to the community.”

The first historic district designated by the city was Brooklyn Heights, within which sits 170 Joralemon Street, site of the former St. Ann’s Episcopal Church, constructed between 1884 and 1886. The congregation left and it became a school in 1986, under the guidance of the LPC, which approved the Packer Collegiate Institute’s expansion in 2002.

Back in Manhattan, there is the now former Washington Square Methodist Episcopal Church at 135 West 4th Street, in the Greenwich Village Historic District. It was built in 1860, but turned residential in 2004. “The building’s narrow and heavy marble primary façade with stained glass windows and even narrower side yards limited opportunities for light and air, which were required for its residential conversion,” Srinivasan said.

“The commission approved openings at the rear elevation to allow for light and air and thus created, in fact, very airy apartments with stunning stained glass windows, a combination that added enormous cache.”

At 142 West 81st Street in the Upper West Side-Central Park West Historic District is the 1893 Mt. Pleasant Baptist Church, which Srinivasan called a “somewhat different project.”

“In this instance, the church remained as an occupant of the building, despite a small congregation. In an effort to generate the necessary resources to fulfill their mission in the community and maintain their house of worship, they developed a plan to retain the space within the building and add a second use, which was residential, to generate revenue,” she said. “The commission… found a way to significantly alter the height, massing, and roofline to allow increased program while preserving the architectural character of the building.” In fact, the move was well-supported by the community when the LPC approved it in October of 2014.

“Civic buildings are typically owned by the city and state and are often strategically located and [are] kind of neighborhood markers,” Srinivasan said. “Public-private partnerships to reuse defunct historic public buildings have resulted in creative economic development solutions to breathe new life into these buildings. Often times, adaptive reuse of civic buildings responds to changing neighborhoods or fulfills a community need. They in turn become catalysts for an area’s revitalization.”

The 14th Regiment Armory at 1402 Eighth Avenue in Park Slope, Brooklyn was built between 1891 and 1895 as a military installation for the New York State Militia. The armory was taken out of service in 1992 and it was transferred to the city in 1996 and used as a women’s shelter. It was designated an individual landmark in 1998 and now serves as a YMCA, with the giant drill space perfect for a running track.

Croton Aqueduct Gate House, now Harlem Stage. Photo by Karen Green/Flickr

The Croton Aqueduct Gate House at 1501 Amsterdam Avenue in Harlem was designed in 1884 and served as a regulator for the aqueduct system that had saved New York City from cholera. It was designated a landmark in 1981. It was decommissioned and between 2004 and 2006 was converted into a performance space for Harlem Stage. That brought “a public and cultural use” to what Srinivasan called a “handsome structure.”

240 Centre Street. Photo by Rian Castillo/Flickr

The former police headquarters at 240 Centre Street is a real gem, especially when compared to its Brutalist Goliath successor – One Police Plaza. The Centre Street building, with its fantastic dome, was constructed between 1905 and 1909, but eventually was inadequate for running the police force of the consolidated City of New York. The building was designated a landmark in 1978 and converted to residential use in the 1980s. “The residential unit beneath the dome clearly reflects tapping into the building’s grandeur in a successful manner,” Srinivasan said.

“When one thinks of adaptive reuse in New York City, the classic prototypes are conversions of industrial buildings, where market forces and changes in industry have affected the land use patterns,” said Srinivasan. “The adaptive reuse of these building types has transformed entire neighborhoods.”

28 Old Fulton Street. Photo by Wally Gobetz/Flickr

One example is Brooklyn’s Eagle Warehouse & Storage Company building at 28 Old Fulton Street in the Fulton Ferry Historic District. Built in the early 1890s, it became an apartment building in 1980.

“The Eagle Warehouse project is a straightforward example of a conversion of industrial to residential use which required minimal exterior changes, such as creating new windows on secondary facades to create required light and air,” Srinivasan said. “However, it is one of the first examples of the use special permit under section 74-711, the zoning resolution to allow landmark buildings to waive use and bulk. This mechanism has had a positive impact on preservation and has enabled [the] LPC to have a larger role in defining the communities in the city.”

25 North Moore Street in TriBeCa is a much more dramatic conversion. It was built in 1924 as a nearly windowless cold storage building. It now sits in the Tribeca West Historic District.

Of course, you can’t have apartments without windows. So, the 1996 conversion required what Srinivasan called a “more aggressive set of changes to accommodate the new use.”

Asphalt Green. Photo by Charles Smith/Flickr

The former Municipal Asphalt Plant at 555 East 90th Street was built between 1941 and 1944, but ceased production of asphalt in 1968. That’s when operations were consolidated to a site in Queens. “…There are these industrial buildings that have been preserved and continuing to resonate their iconic presence, but now provide a public use. In the case of the municipal asphalt plant, careful alterations allowed the successful conversion into a recreational center,” said Srinivasan. The site is now known as Asphalt Green.

Srinivasan then went through three commercial buildings. “Commercial buildings, on the other hand, are often well-suited for residential uses, often having floor plates and layouts that allow light and air and building systems that rarely require significant alterations to the exterior,” she said. “Typical changes include replacing windows, installing HVAC equipment, and installing terrace dividers and setbacks, most of which can easily be accommodated without affecting the historic appearance of these buildings. However, there are some projects that have tested our minds and required a different type of intervention.”

Knickerbocker Hotel. Photo by Several seconds/Flickr

The Knickerbocker Hotel at 1462-1470 Broadway and 42nd Street, now 6 Times Square, was completed in 1906. However, the onset of Prohibition led to a conversion to office use in the 1920s. In 1988, it was designated a landmark. Since 2010, it has again been a hotel, but modifications were required for it to meet current codes.

“The commission approved new entrances, new storefronts, and signage, altogether rather modest changes,” Srinivasan said. “But we also allowed modifying the footprint by removing the rear portions of the building and relocating the square footage in a penthouse addition to support a viable project.”

The former Cities Service Building at 70 Pine Street in the Financial District is wonderful, with its Art Deco style and needle spire. When it was completed in 1932 at 952 feet tall, it was the third tallest building in the world. Eventually, it was sold to the financial firm AIG and became known as the American International Building. It was landmarked in 2011 and, since 2013, it has been undergoing a residential conversion.

“The particular challenge to converting office buildings to residential is addressing interior designated lobbies that were open to the public and now require separation and security between the multiple uses,” Srinivasan said. “In the case of 70 Pine Street… the commission approved five minimalist partitions in the designated office lobby to provide division between the uses in a discreet manner to preserve the legibility of the Art Deco-defining volume and ornament.”

The former American Telephone & Telegraph Building at 195 Broadway was commissioned by the telecommunications company and built between 1912 and 1922. It was AT&T’s headquarters until it moved to 550 Madison Avenue, which became Sony Tower. 195 Broadway went on to serve as Western Union’s headquarters and continues to serve as an office building. In 2006, it was designated an individual landmark and its lobby was designated an interior landmark.

That lobby was converted into retail space. “The commission approved a complex set of glass walls in corridors to accommodate a retail galleria [and] multiple retail stores in the grand… lobby,” Srinivasan said. “The reuse of portions of the building to create retail shops was also seen as a part of a larger goal of revitalizing Lower Manhattan and found an easy synergy with pedestrian connections to the adjacent Fulton Street transit hub.”

Even with all of those successes, the commission continues to face challenges. “On the issue of density, we recognize that the demand for housing has always been a catalyst for adaptive reuse projects, but we can project that the city will find itself with greater housing needs in the future,” Srinivasan said. With the rise of the city’s population and the increase in the cost of living, there’s a dire need for affordable housing. Historic buildings… could supply part of that demand.”

An example is Cedars/Fox Hall at 745 Fox Street in the Bronx’s Longwood Historic District. Fox Hall was a standalone residence built around 1850, but since 2009 has been the main common space and office area for a 95-unit affordable housing development for formerly homeless families, sponsored by Lantern Community Services.

“Improving resiliency is an issue that, although not necessarily new, is now receiving much attention in aftermath of Hurricane Sandy and a growing awareness and acceptance of climate change science and its anticipated effects, Srinivasan said. “Often, resiliency measures require changing the level of the building above the flood plain.”

“The adaptive reuse of long-vacant storefront warehouses, such as Empire Stores and the Tobacco Warehouse alongside Brooklyn Bridge Park, has resulted in different approaches to addressing the issue of resiliency and flood protection,” she said. “While Empire Stores proposed flood barriers that could be deployed in the case of a storm surge, the tobacco warehouse was repurposed to withstand water pressure by allowing the water to flow through the ground floor of the building without disturbing historic fabric.” (More on the tobacco warehouse shortly.)

“In the future, modern structures will come of age and become eligible for landmark status,” Srinivasan said. A structure or site must be at least 30-years-old to be eligible for designation. “The seamless integration of interior and exterior spaces is a signature of modern design and the commission will have to consider the interplay in future instances of adaptive reuse.”

510 Fifth Avenue. Photo by Beyond My Ken/Wikimedia Commons

At the Manufacturers Trust Company Building at 510 Fifth Avenue, the use went from office and bank in 1954 to retail in 2011. Both the original construction and the conversion were done by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.

“The commission considered a new tenant, while maintaining the striking mid-century modern characteristics, including its transparency and luminous ceiling. In this particular case, the ground floor interior has been altered prior to its designation, which resulted in the loss of transparency,” Srinivasan said. “The commission approved changes to allow a new use and, while the interior escalator was relocated, the transparency at the ground floor and the luminous ceiling were restored, thereby returning the building to its intended experience from inside and out.”

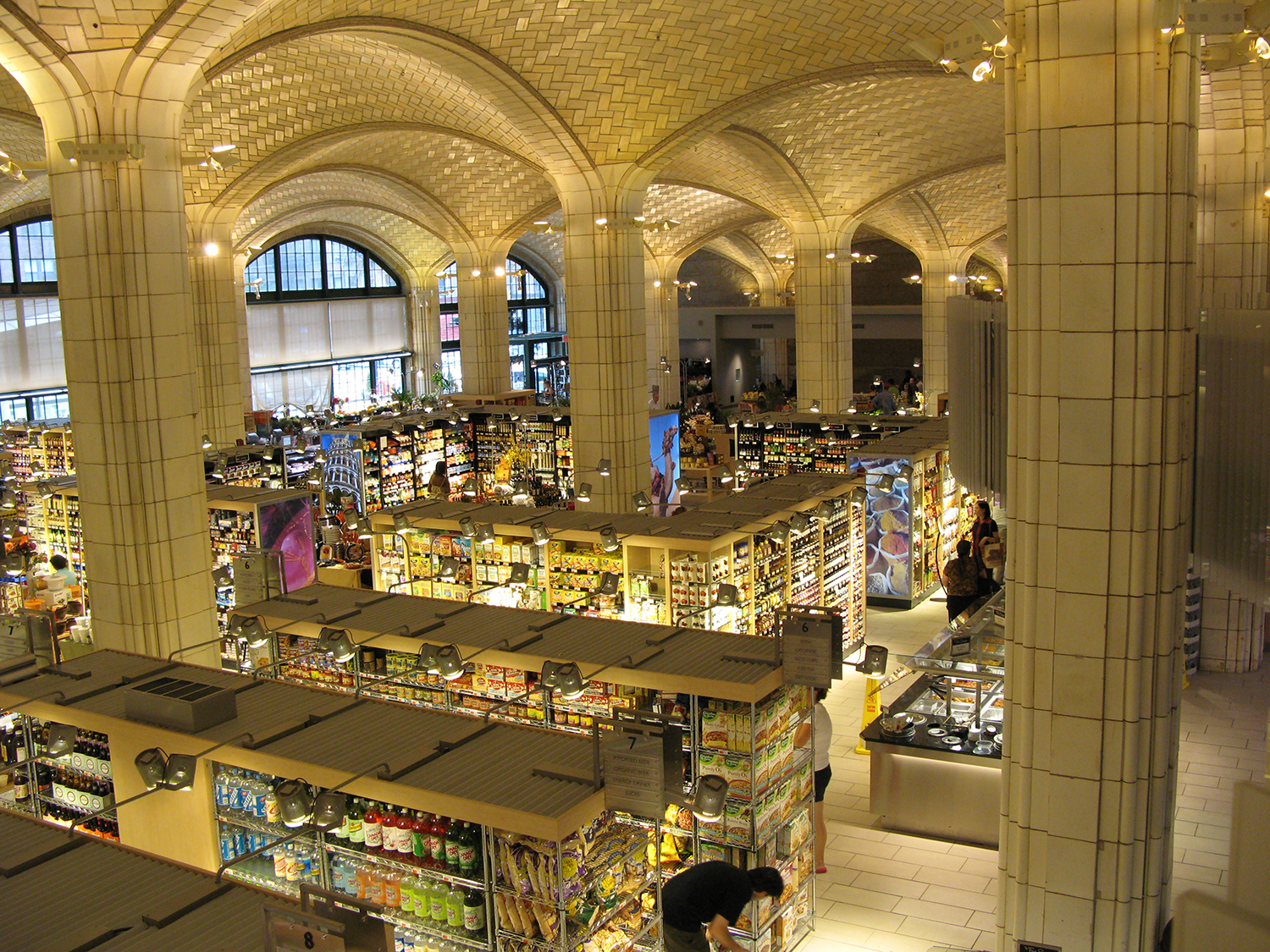

The Food Emporium under the Queensboro Bridge. Photo by Drew XXX/Flickr

Then there are unusual spaces, such as the former service space under the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge, with its Guastavino tile ceilings. It became a Food Emporium, possibly the most beautiful supermarket space in the country. But the market is closing. “The commission will need to take a fresh look as the space is altered for another use,” Srinivasan said.

“I would just like to end by noting that in adaptive reuse projects on landmark properties, when architects and designers are encouraged to study and appraise the historic characteristics of buildings and districts, it results in amazing, creative, and innovative contemporary designs,” Srinivasan said in her closing remarks. “Projects that people marvel [at] and projects that people are drawn to, projects that are heavily photographed, and projects that become a part of the history of the very same buildings they aim to protect.”

After Srinivasan spoke, it was the architects’ turn. The first up was Jonathan Marvel of Marvel Architects, which converted the former tobacco warehouse alongside Brooklyn Bridge Park, just north of the Brooklyn Bridge, into a theater and event space run by St. Ann’s Warehouse. It opened in October.

St. Ann’s Warehouse at the former tobacco warehouse. Photo courtesy St. Ann’s Warehouse via Curbed NY

The 19th century warehouse had once been five stories in height, but that was reduced. Then a fire tore the roof right off, leaving it what Marvel called a “beloved ruin.”

“No playbook really could be assigned to this project,” Marvel said. “It’s under the guise of resiliency, but it could also be seen under the guise of how to take over an old ruin. It’s not an adaptive reuse of anything but some brick walls.” He called it a case of “constraints” versus “discretionary moves,” those being the old structure and the new construction, respectively.

St. Ann’s Warehouse theater space. Photo courtesy St. Ann’s Warehouse via Curbed NY

“We’re not gonna touch the brick walls,” he said, but they had to accommodate a 31-foot height for the project. Six months were spent to find the “appropriate vocabulary” for the “layers of spatial intervention” required for the theater’s program.

They had to protect the structure. Instead of blocking the water that might come up from the river, they’ll allow it to flow through the ground floor, but won’t have any electrical or mechanical equipment below four-and-a-half feet.

St. Ann’s Warehouse. Photo by David Sundberg/Esto via Marvel Architects

Marvel is particularly in love with the way the Brooklyn Bridge is framed in one of the lobby windows.

Gregg Pasquarelli of SHoP Architects had to deal with the now former Steinway Hall (the second such hall) at what is now being called 111 West 57th Street. The Steinway Hall building was completed in 1925, landmarked in 2001, and is currently being integrated into a supertall residential tower, slated to rise 1,428 feet into the air. “It was very important to us that the building felt like it was a New York building,” Pasquarelli said.

“What are [the aspects of] all the towers that we all love as New Yorkers?” he asked. “It’s materiality. It’s proportion. It’s the way in which the tops meet the sky.” He said we are in the “next golden age, if you will, in skyscraper design.”

The 80-foot by 60-foot building will feature one unit per floor and setbacks, which are a post-Equitable Building feature that he said “make a New York building a New York building.”

In this case, there will be a “feathered setback where you have a hyper-articulated series of pilasters, each one creating a setback that turns into this sort of gentle arc where the building actually gets down to only eight-feet-wide when it gets up to the top and kind of disappears into the sky.”

The materials will be terra cotta and cast bronze. In fact, there will be 26 different shapes of terra cotta and six different colors of cream meeting at a 200-foot-tall sculpture, if you will, at the top.

The building’s slenderness ratio will be an astounding 23.5:1. “Far and above, an engineering feat,” he said. “And will be a remarkable proportioned building that I think really takes these kind of historic materials, uses them in an incredibly contemporary way, and connects to the historic landmark at the bottom.”

Harry Kendall and Todd Poisson of BKSK Architects are working on the adaptive reuse of the landmark former Tammany Hall building at 44-48 Union Square East (a.k.a. 100 East 17th Street). Completed in 1929, it used to be the meeting hall of the Tammany society, but has since been a multi-purpose commercial building. When its restoration and renovation, including a dome topper, is complete, that will still be its purpose. So, in this case, it’s less of a case of new use and more of a case of breathing new life into an aging structure.

“When we looked deeper and deeper at Union Square, we came more and more to the conclusion that Union Square was never really a place of quiet decorum. It’s not a contemplative city park,” Kendall said. In fact, the building replaced a larger structure on the site, which supports the idea of enlarging the building.

While Tammany Hall was actually named for Lenape Chief Tamanend, who negotiated a treaty with William Penn, it is known for corruption and the design team wants to change that. “We wanted to rebrand our building, reuse that name, tell the story that everyone has forgotten, turn the building into something new,” said Poisson. The dome, meant to evoke a turtle shell, is part of that. It references the Native American myth of a turtle (or tortoise) emerging from the water and creating land. Turtle Island is actually a little-known nickname of Manhattan.

Construction is set to begin in the spring of 2016.

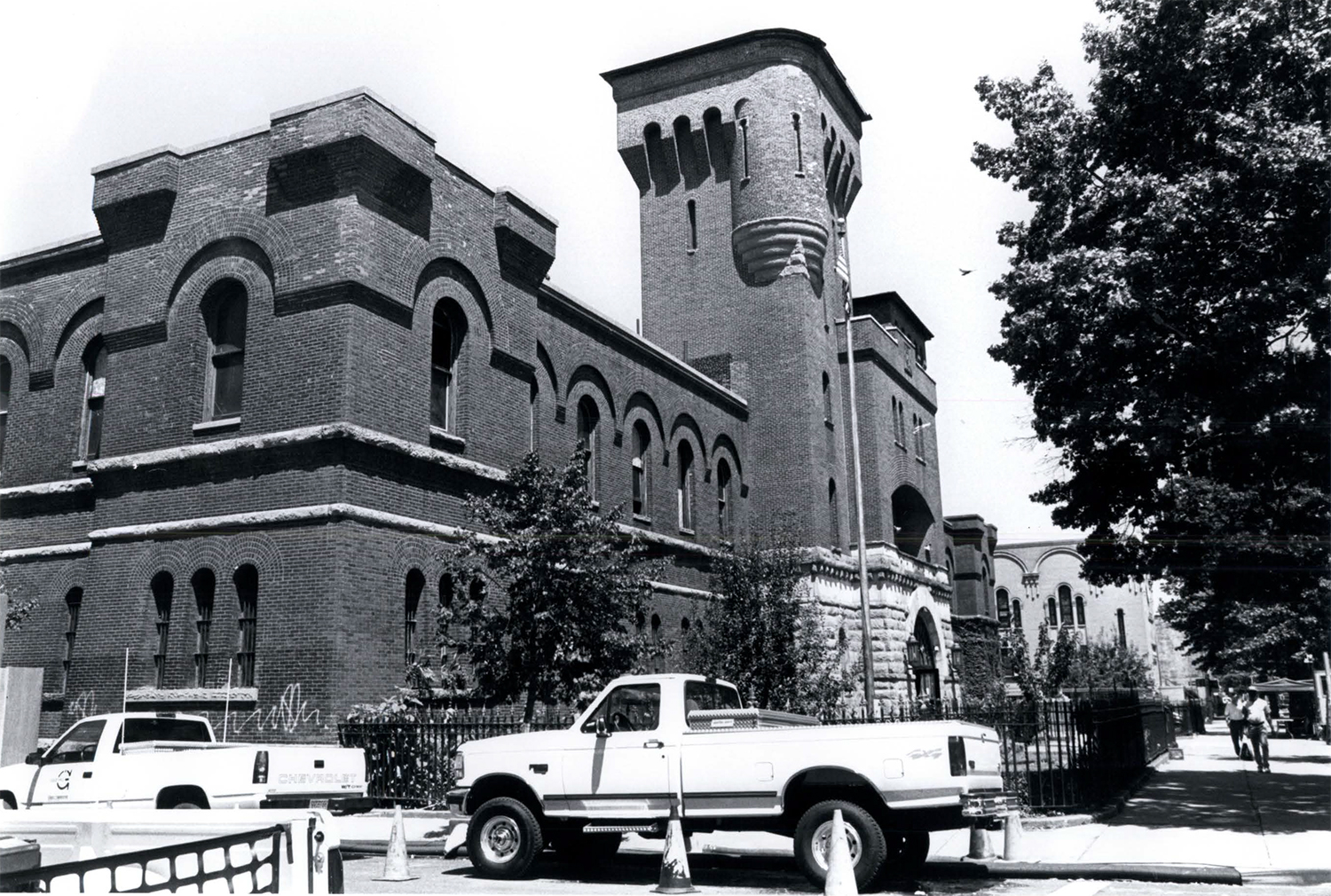

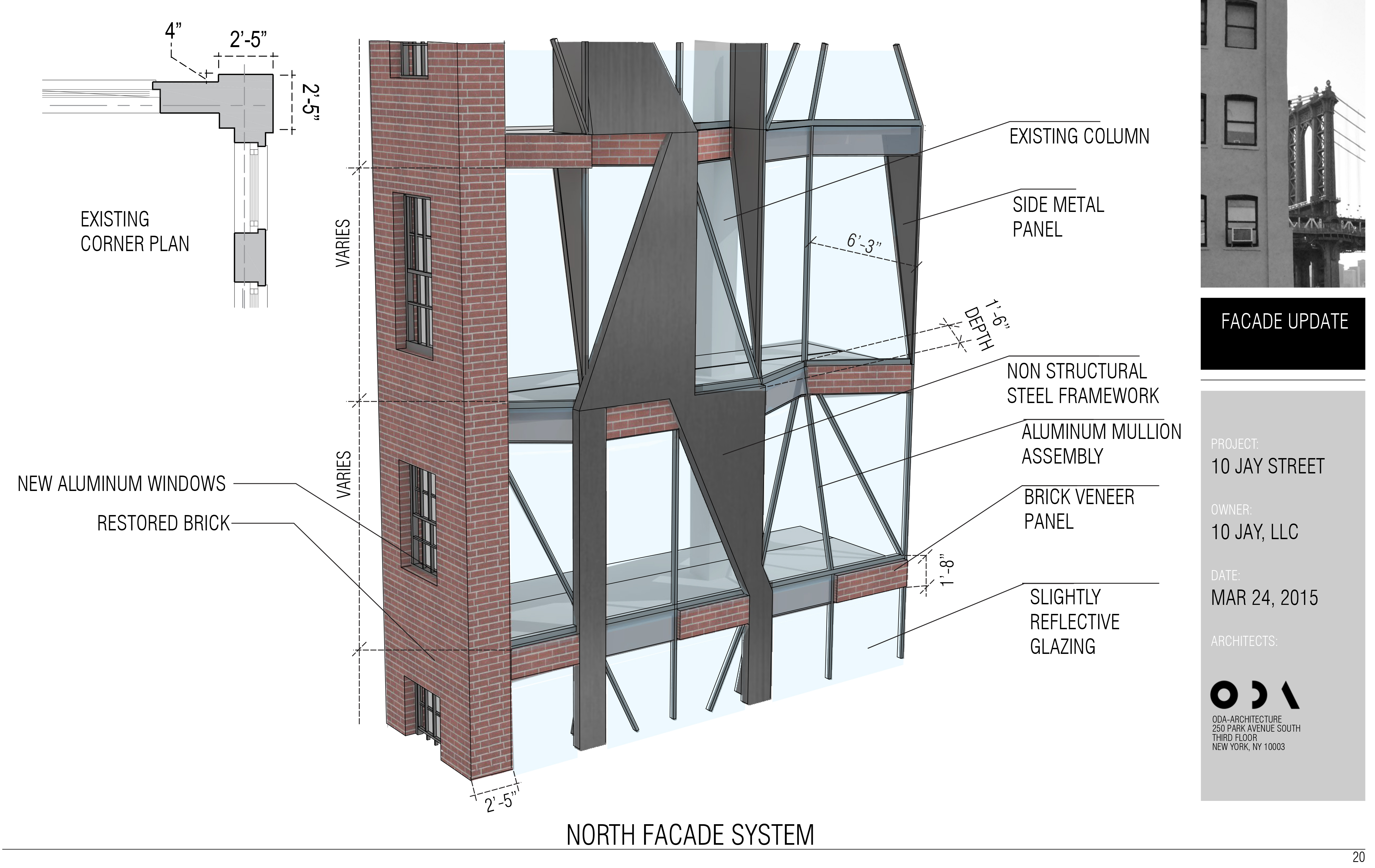

Eran Chen of ODA New York is working on the conversion of 10 Jay Street in DUMBO. Originally, it was going to become a condominium building, but the developer is now making it into a commercial building. It was originally completed in 1898 as the Arbuckle Brothers sugar refinery, but was converted into a warehouse in 1945. Sometime in that decade, an entire half of it was removed and a new, unsympathetic façade, put in place.

The new facade will feature 60 percent glass, 27 percent steel, 10 percent brick, and three percent spandrel. It will evoke sugar cyrytals, the truss form of and steel materiality of the Manhattan Bridge, the steel and brick materials found in DUMBO, and the reflective nature of the East River.

“To all of the non-architects in the room… I really applaud you because I think preservation and adaptive reuse should be a subject that is important to all of us,” Chen said. “Preservation is really in the DNA of every growing city. I think we see cities in the developing world where they dismiss their history and I think over time that loss, which is part of our culture, is going to be quite painful.”

“Our job as architects is… we’re designing the present, relying on the past for the future,” he added. “When we talk about preservation, it’s not just about brick and mortar, it’s a lot about the spirit and sort of an ongoing story about who we are today and where we came from and there, sometimes, preservation also deals with telling or creating a narrative of our life.”

Frank Mahan of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill is working on the conversion of the former One Chase Manhattan Plaza, built by SOM in 1964 and designated a landmark in 2009. JPMorgan Chase sold the building in 2013 and now the Chinese developer Fosun is redeveloping it from single-tenant into a multi-tenant office building. That includes the redevelopment of the two-acre plaza and the space below it, formerly bank branch and back of house space, into new retail.

“Just like the nature of banking is changing in the last 50 years – you don’t need 30,000 square feet for a bank branch anymore – the nature of Lower Manhattan has radically changed in the last 50 to 60 years,” Mahan said. “This building was completed in 1964. It was a commercial office building in a commercial office district and now there are more than 60,000 residents in Lower Manhattan. It is a bustling 24-hour neighborhood. It has radically changed.”

Now they need to make better use of what he called an “unbelievable asset.” They need to turn the 300,000 square feet below the plaza into a space that can support the space above it.

“[We need to] adapt our buildings so they’re not frozen in time and use them as an opportunity for preservation,” he added. “I think this is a really important topic that architects are going to have to grapple with more and more in the very near future, particularly as a lot of our city’s mid-century building stock matures, if you will.”

Gregg Pasquarelli, Eran Chen, Todd Poisson, Harry Kendall, Frank Mahan, Catterina Roiatti of the AIA’s Historic Buildings Committee, and Jonathan Marvel. Photo by Evan Bindelglass.

The projects highlighted above are only some of the adaptive reuse efforts in New York. There are many more successes and, if we all do our jobs right, many more to come.

Happy Holidays!

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

What’s not discussed – the out of control costs associated with owning & maintaining a Landmarked building. The recent renovation of St. Patricks was approximately $3,100/sf, and the average grant from NYS is 12,000 = 4 sf renovated (excluding legal & paperwork costs.)

who pays??

I’m pleased to say that RKTB Architects (at the time Rothzeid Kaiserman & Thomson) designed the afore-mentioned conversion of the Eagle Warehouse Apartments at 28 Old Fulton Street. Another of the many significant adaptive reuse projects completed by RKTB but not mentioned here was 455 Central Park West, which transformed America’s first cancer hospital into a residential condominium in the early 2000s. RKTB designed the adaptive reuse of the landmark which was combined with a new, 27-story tower designed by Perkins Eastman.

Originally built in 1884, the hospital was converted into a notorious nursing home known as “The Towers” in 1956 that was subsequently abandoned in the 1970s. By the time RKTB became involved with its redevelopment the building had fallen into advanced stages of decay, posing a number of major structural challenges. Careful research was required by the Landmarks Commission and the State Historic Preservation Office to restore all aspects of the exterior. Rotten roof beams necessitated the removal of the entire historic roof which was rebuilt with permanent material, and the deteriorated interior structure required removal and replacement with a new concrete structure. Significant portions of the landmark’s interior, such as a large chapel space and a wrought iron grand stair, were also restored to become highlighted features of the new program. The project received 5 awards, including a Lucy G. Moses Preservation Award from New York Landmarks Conservancy and Project of the Year: Adaptive Reuse Award from New York Construction.