In April 2014 we interviewed developer Sam Charney of Charney Construction and Development. Among other things, he spoke about Long Island City’s 11-51 47th Avenue, now known as the Jackson. Since then, we have followed the building’s progress, starting when the site was cleared at the end of 2015 up until its recent topping-out. Today we revisit the project with Charney and the building’s architect, Chris Fogarty of Fogarty Finger.

Looking north from Jackson Avenue, with the Jackson on the left, MoMA PS1 in the center, and One Court Square on the right. Photo by the author.

Long Island City began its post-industrial transition two decades ago, yet in the two and a half years since our last meeting, the pace of development has become dizzying. A new skyline has risen around Court Square, spurred by favorable zoning and adjacency to Midtown. Manufacturing and auto repair facilities are rapidly being replaced by housing and retail. Like many of the city’s post-industrial enclaves, the neighborhood has attracted artists, with Long Island City boasting among the highest densities of studio spaces and galleries in the city. The Jackson sits across from the MoMA PS1 museum, which is itself catty-corner from 5Pointz, a world-renowned graffiti destination that is being replaced with a two-tower mixed-use project that will feature new space for outdoor murals.

Rendering by Brick Visual

The Jackson draws design inspiration both from the neighborhood’s manufacturing legacy and its bohemian present. “We took Long Island City’s industrial past and the immediate historic context provided by PS1 head on, and conceptualized a bold two-story-high rhythm of exposed concrete across the entire façade,” Fogarty elaborates. “The large concrete frames are juxtaposed with layers of wood and black metal slab covers. The window wall spans the full floor height and evokes an industrial character.”

While loft-style windows are a universally-celebrated design element, exposed concrete tends to be more challenging. The versatile material is notorious for producing results that range from sublime to abysmal, depending on factors ranging from design intent to builder expertise. At the Jackson, the distinctive concrete grid appears simultaneously gritty and refined. “We used custom plywood forms and form ties for the exposed concrete,” Fogarty tells us. “It was designed to be 7000 PSI, with finer than typical aggregate in order to get a smooth finish. We did not add color admixtures in the concrete, because we wanted to express the natural color variations that occur.”

The area’s art scene will be referenced more directly by two common area installations by artist Tom Fruin. The double-height lobby will have an 18-foot high by 10-foot wide backlit collage, framed in blackened steel, in keeping with the overarching industrial theme.

The unorthodox building site, roughly square with a chamfered corner at Jackson Avenue, presents advantages as well as challenges. The architect acknowledges that laying out apartments in the irregularly-shaped structure was tricky.

On the plus side, the facade presents 200 feet of eastern and southern exposure as it faces 47th and Jackson avenues and 21st Street. But while the unobstructed front façade will be a source of abundant sunlight, it is the rear facades that have the most iconic views, showcasing the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge to the north and the Midtown skyline to the west. The building’s 125-foot-high concrete frame rises well above its low-rise neighbors, keeping the viewshed unobstructed.

“As far as possible we have oriented the units to maximize views to the city from the living spaces. All city-facing units have balconies or terraces off the living rooms,” Fogarty said. This portion of the building is topped with a dramatic design element, where the curtain wall peels back from the concrete frame to form a multi-level terrace. Other terraces, shaped by the building’s zoning envelope, open towards the street.

Given Long Island City’s ongoing renaissance, skyline views are no longer synonymous with just Manhattan panoramas. The building’s northeast-facing windows look upon the ornate rooftop dormers of the adjacent museum, with the new skyline clustered around One Court Square rising in the backdrop. The new towers embody the tremendous neighborhood potential that Charney noted in our 2014 interview. “I think what’s happening in western Queens right now is really special,” the developer said at the time. “With land prices trading for roughly half of Williamsburg, and better transportation options, people are realizing the potential of the sleeping giant that is Long Island City. There is nowhere near enough condo stock in the neighborhood to meet demand, but I think developers are picking up on that, which is what’s driving land prices up.”

As the skyline grows, so do the local real estate prices, which begin to approach those in Brooklyn. Growth in Manhattan indicates that demand in Long Island City will continue to increase in the coming years. The 7 train’s Vernon Blvd-Jackson Av station, four blocks southeast of the Jackson, puts Grand Central Terminal within a single-station ride, where the nation’s largest commercial district would soon see a major boost thanks to the pending Midtown East upzoning.

Hudson Yards sits one mile to the west, at the 7 train’s new terminus. “The buyers are capitalizing off the 7 line extension and working in Hudson Yards,” Charney remarks. “We’ve found young professionals in the tech industry, who have offices in Hudson Yards, are buying in the building, and prefer Long Island City to other viable residential locations off the 7 line.”

Though the 7 train sits nearby, the closest subway to the Jackson sits literally right outside its front door, where the 21 Street-Van Alst station of the G train puts Greenpoint within a single stop. The neighborhoods of Astoria and Sunnyside are similarly accessible to the north and east, respectively. Long Island City still struggles to compete with the well-established dining and nightlife scenes of its neighbors, yet its own attractions lie within walking distance. “Vernon Boulevard is rapidly becoming a really exciting retail strip,” Charney remarked two years ago. “I think that from Vernon to Jackson there are many pockets that will infill by 2020. Interestingly, Jackson runs from Hunter’s Point to Court Square — so as construction heats up in Court Square, the development pressure will come from both sides. This will result in Jackson becoming another major retail boulevard like Vernon.”

As expected, development is heating up along Jackson Avenue as residential and retail projects contines to replace warehouses and parking lots. As the neighborhood was geared towards manufacturing for much of its history, the city is investing $38 million to improve the streetscape. Still, there is clear potential for improvement along the avenue, which is in need of more measures to soften the effect of traffic that surges during the morning and evening rush hours.

The BP gas station, which occupies a small triangular block along the avenue between the Jackson and the museum, is a perfect candidate for a conversion into a public plaza, just as the John F. Kennedy commuter parking lot at the foot of the Queensboro Bridge was converted into the Dutch Kills Green a few years ago. Just as the Green became a focal point for the congested Queens Plaza, this new space, which would similarly sit atop a subway station, would anchor the growing Hunters Point East neighborhood. The building rendering hints at this idea, although there are no known plans for such a conversion at the moment. Since the city is in no rush to purchase the gas station and convert it into public space, a private developer could buy the property in tandem with a nearby lot. The developer would transfer development rights to the adjacent site, while also gaining another bonus in allowable construction in exchange for creating this much-needed public space.

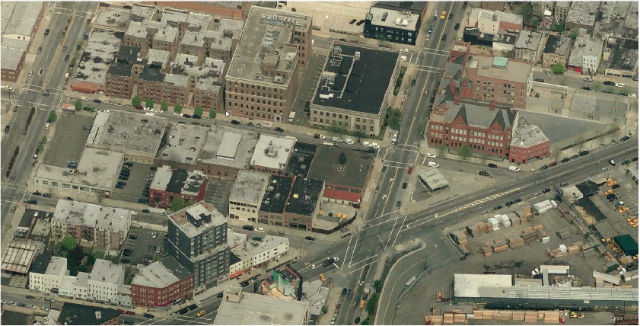

11-51 47th Avenue, prior to construction, at the image center, at the intersection of Jackson Avenue (diagonal) and 21st Street (vertical, center). The suggested plaza site is on the triangular lot (center right), with MoMA PS1 to the north. Credit: Charney Construction

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

I waited all week to view Long Island City, and at last the visit arrived with construction comes on.