In New York City, as everyone knows, there are mostly two kinds of new construction: luxury market-rate development, and subsidized “affordable housing.”

But near the end of the 2 train in the Bronx, on the corner of East 216th Street, developer Mark Stagg’s Stagg Group has started work on 3677 White Plains Road, a new apartment building that will be neither luxury nor fully subsidized. The apartments will be one- and two-bedrooms, and the latter are expected to rent starting around $1,700 on the open market (like his other projects nearby), and less for the 20 percent that are subsidized by cheaper financing on top of the 421-a tax abatement that all new apartment buildings in the Bronx get.

“Our model is that we provide market-rate apartments for working-class people,” said Stagg. “The nurses, nurses’ aides, firemen, policemen making $40,000 to $80,000. Those people need a place to live.”

This sort of new market-rate development, targeted at the middle class, used to be a mainstay of New York’s real estate industry, back when it was churning out modest row homes and garden apartment buildings. It has since all since evaporated, eaten away by gentrification and rising land prices emanating from the city’s core, and anti-development forces on the fringe.

But it isn’t completely dead, as the construction on White Plains Road shows. And with any luck, de Blasio may be able to start to revive it, if his housing team can harness the energy of some of the city’s lowest-profile builders.

Mark Stagg, the Bronx’s biggest market-rate builder, got his start doing much smaller projects.

“I started building one- and two-family houses. Then three-family, then four-story walk-ups, then…” he said as he gestured to the hole in the ground that’s slowly giving way to a 118-unit building.

The sorts of row homes that Stagg used to build were, up until recently, the mainstay of New York City’s affordable market-rate industry. But the Bloomberg years were not kind to the city’s small homebuilders.

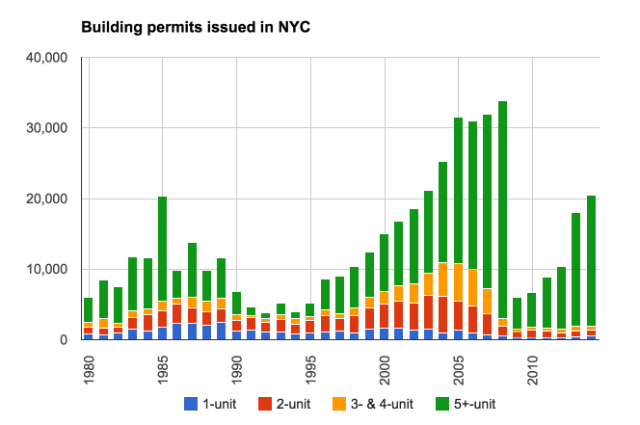

Amanda Burden’s Department of City Planning was ruthless in downzoning single-family neighborhoods where two- and three-family homes could still be built. Citywide, permit approvals for two- through four-family homes peaked in 2004, a few years before the top of the market cycle, and have remained close to zero even as larger-scale construction has mostly returned.

Stagg graduated from developing smaller buildings just in time, bringing on former Bronx Borough President Adolfo Carrión, and he now works exclusively on larger projects.

Larger projects, however, are more expensive to build and tougher to finance, and permitting numbers show that Bronx builders more broadly have yet to make up for the loss of two- and three-family development sites with bigger buildings. Approvals in the borough were down in 2014 to just 1,885 units, and it’s almost entirely due to the deficit of smaller buildings. Permits were issued for just 140 units in two- through four-family buildings last year, down more than 90 percent since 2007, compared with a shortfall of just 30 percent for larger structures.

But the de Blasio administration is not interested in revisiting the downzonings of the Bloomberg years, according to spokesman Wiley Norvell. This means that ramping up the production of larger buildings like Stagg’s is the only hope for reviving the market for reasonably priced market-rate buildings in the Bronx.

“We’d have to go vertical,” Stagg answered when asked by YIMBY how the mayor’s team could accommodate builders like him. “Give us more density, and then we’re able to produce more units.”

He pointed to the Jerome Avenue corridor, which the administration identified last year as a possible target for a rezoning, along with Webster Avenue to the east and Broadway to the west.

Another zoning move that could encourage development is the Department of City Planning’s attempt to eliminate parking requirements for below-market housing, and offer developers of mixed-income projects like Stagg’s a chance to request reductions in the amount of required parking for the market-rate portions of buildings.

“Naturally, it would be cheaper to build less parking,” said Stagg. “As we secure transit-oriented sites, we think it makes sense to reduce parking at those locations.”

And finally, Stagg said that the 421-a program must remain in place if he is to continue building in the Bronx.

“We have to pack our bags,” he replied when asked about the possibility of eliminating the program, as some affordable housing advocates have suggested. “We couldn’t do it.”

Whether the de Blasio administration can bring production in the Bronx back up to levels seen in the mid-2000s remains to be seen. But encouraging builders like Stagg, whose new units are cheaper than even the most decrepit old apartments in most Brooklyn neighborhoods, is imperative if the mayor wants to boost construction beyond levels seen during the Bloomberg years.

Talk about this topic on the YIMBY Forums

For any questions, comments or feedback, email newyorkyimby@gmail.com

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews