The year 2015 marked the near-complete demolition of Times Square’s second oldest structure. 701 7th Avenue opened at Times Square’s northeast corner on West 47th Street in January 1910. Initially called the Columbia Amusement Co. Building, the property was known by a variety of names during its century-long life span. Like the slightly older yet much more famous One Times Square at the opposite end of the square, the building engaged in the neighborhood’s classic disappearing act, where giant billboards seen by millions made their renovation-scarred hosts all but invisible. But behind the ads, standing on a 16,000-square-foot lot, was a building with a history as dramatic and diverse as that of the famous square on which it stood.

Looking northeast from the intersection of 7th Avenue and west 47th Street. February 2016. Photo by the author

In the 1870s, the intersection of Seventh Avenue and Broadway was home to Manhattan’s horse carriage district, named Longacre Square after its London counterpart. With the introduction of cars to the general public, the area became New York’s first auto row. The neighborhood was already built out by the end of the 19th century, but despite its density, it was still seen as peripheral when compared to the business and entertainment districts to the south.

The Theater District began its northbound migration from the 20s streets portion of Broadway in 1893, when the Empire Theatre opened its doors at 1430 Broadway between 40th and 41st streets. In 1895, it was followed by the much larger Olympia Theatre on Broadway and West 44th. The most dramatic change came in 1904 with the opening of Hotel Astor and Times Tower within a block of one another. The latter rose above a new station on the city’s first subway line. The tower replaced the nine-story Pabst Hotel, which lasted only four years between 1989 and 1902. At almost 400 feet, the newspaper’s building became one of the city’s three tallest, and prompted the intersection’s renaming to Times Square. To promote its new headquarters, the newspaper set off fireworks from the building’s roof on New Year’s Eve 1904. Although the fireworks were soon substituted with the “dropping of the ball,” the building remains at the center of the nation’s most prominent New Year’s Eve celebration.

Times Square looking north from the Times Tower between 1904 and 1909. Hotel Astor (1904) is on the foreground left, Olympia Theatre (1895) on the foreground right, and Studebacker Building (1902) in the upper center. 701 Seventh Avenue would rise to the right of Studebacker. Credit: Museum of the City of New York, Byron Collection

As new development crowded the south end of the intersection, change came to the northern end at a slower pace. Its first major landmark was the 10-story Studebacker Building. Built on West 48th Street in 1902, one block north of the square’s terminus, it was one of the last additions to the Longacre Square auto district. Studebaker left the building for 57th Street just eight years later, as the Automobile Row, displaced by an influx of theaters and hotels, continued its exodus uptown along Broadway.

The blocks around Studebacker were still lined with low-rises, which included the townhouses at 7th Avenue and West 47th Street at the square’s northeast corner. Unlike most of its neighbors, the corner building met the commercially attractive 7th Avenue with a blank wall, which, by May 1909, was painted with a sign that announced, “On this site will be erected a ten story office building and the Columbia Theatre.”

Future site of the Columbia Theatre. May 1909. Image by Brown Brothers via the New York Public Library Digital Collections

Founded in 1902, Columbia Amusement Company, also known as the Columbia Wheel or the Eastern Burlesque Wheel, pioneered the “wheel” concept where burlesque shows rotated through a theater network across the eastern half of the country, avoiding inter-theater competition and guaranteeing work for the performers. The circuit, headed by Sam A. Scribner, was noted for its “clean” shows as opposed to the more risqué competitors.

New York Times ad. 1920. Image from the Museum of the City of New York

By mid-1909, the company began building its anchor theater and headquarters in the rapidly emerging Theater District. Noted theater architect William McElfatrick drafted the 10-story, 128-foot tall-building.

By early October 1909, another set of scaffolds rose in the northern half of the square. Under the scaffolds, workers were busy molding eight tons of white plaster into the statue named “Purity,” or “Defeat of Slander.”

Purity, or Defeat of Slander, at Times Square and West 46th Street. Circa 1909. Image by Robert L. Bracklow via the Museum of the City of New York

Designed by Leo Lentelli, the nearly 50-foot-tall statue featured a robed woman standing upon a pedestal, holding a shield in her left hand, and looking down upon the street with a stern expression. She was commissioned by the notorious political gang of Tammany Hall, who figured it to be the best way to announce their “pure and noble” intentions to the public after an opponent accused them of crooked practices. Unfortunately for the politicians, nature was not on their side when heavy rains melted the plaster sculpture two months later.

Columbia Theatre. 1910. Image from Architects’ and Builders’ Magazine via Wikipedia

The Columbia Theatre opened on January 10, 1910, in a grand ceremony attended by a number of dignitaries. The Beaux Arts styled “Home of Burlesque De Luxe” held 1,385 seats on its main floor and on the two balconies. The ceiling above the stage-capping proscenium arch was adorned with “The Goddesses of the Arts” mural painted by Arthur Thomas. While the theater predated both air conditioners and indoor smoking bans by many years, it boasted a ventilation system for removal of tobacco smoke.

Columbia Theatre interior. 1910. Image by White Studio from Architects’ and Builders’ Magazine via Wikipedia

Ceiling mural. 1910. Image by White Studio from Architects’ and Builders’ Magazine via Wikipedia

Theater interior. Image from the New York Tours By Gary blog

The white stone façade was particularly lavish on the first three floors and at the cornice-framed top level. A narrow alleyway with a fire escape separated the building from its Seventh Avenue neighbors.

Columbia Theatre (right) on Seventh Avenue, looking east. 1915. Image from the New York Public Library Digital Collections

Though the building appeared as a solid, rectangular block from the square and most other vantage points, its imposing presence was almost as flimsy as a stage set. The improbably shallow top floors, arranged in an L shape, measured under 20-feet-wide, which explains why the imposing structure contained only around 40,000 square feet of floor space. The brick walls wide enough for only a single window bay could be glimpsed when looking up from certain sidewalk angles.

While all floors were functional, their main purpose was to serve as a veneer to cover the theater. Little did the architect know that these floors would eventually double as an anchor for larger-than-life billboards.

Times Square’s billboards, also known as spectaculars, grew increasingly large and numerous since the turn of the century. By 1917, the Columbia Theatre’s 7th Avenue sign was replaced with a larger successor. New rooftop spectaculars, roughly 60 feet in height, faced the square and competed with the advertisement array across the street, which towered about 150 feet above the busy sidewalk.

Northern end of Times Square, with Columbia Theatre on the right. Circa 1917. Image by Eugene L. Armbruster via the New York Public Library Digital Collections

To keep up with the competition, the Columbia Theatre switched its “clean” burlesque to more risqué content by 1925, and decked out the theater’s square-facing corner was with a marquee that ran the building’s full height.

Columbia Theatre in the 1920’s. Image from the New York Tours By Gary blog

Still, these changes were not enough to save the theater, which closed in 1927. In 1928, Walter Reade bought the building and hired architect Thomas W. Lamb to overhaul the theater into an Art Deco movie palace. The new Loew’s Mayfair Theatre was operated by the RKO studio and showed only the studio’s own films. By 1930, the Beaux Arts interior was replaced with dramatic Art Deco décor. The new lobby sat under a dramatic vaulted ceiling, where pointed flourishes converged upon a star-studded “night sky.” The two theater balconies were replaced a massive, singular successor. The tobacco ventilation system gave way to air conditioning.

Mayfair Theatre interior, with the renovated balcony. Image from the New York Tours By Gary blog

Mayfair Theatre as seen from Times Square. Image from cinematreasures.org

Exterior alterations were equally dramatic. The alleyway to the north was filled in with a narrow six-story wing. Next to it, the Beaux Arts façade was replaced with colorful, Art Deco terra cotta that marked the new theater’s entrance. A new marquee ran above the sidewalk, topped with a massive, illuminated “Mayfair” that faced the square and ran from the fourth floor almost to the top. Two large billboards covered the windows on either side of the “Mayfair” sign and promoted RKO’s movies playing within. For the 1932 film Birds of Paradise, the sidewalk marquee was topped with a lush display of “greenery.”

In 1937, the site just north of the short-lived plaster “Purity” sculpture became home to the smaller, stone statue of Chaplain Francis P. Duffy. Since then, Times Square’s northern end became known as Duffy Square.

When the Brandt Theatres chain took over by the 1950s, the new owners replaced Mayfair’s iconic marquee with a single, curved billboard that rose to the eighth floor, where the tradition of dramatic movie advertisements continued.

701 Seventh Avenue circa 1951. Image from cinematreasures.org

By the 1950s, the Brandt Theatres chain took over and replaced Mayfair’s iconic signage with a single, curved billboard, which covered an even greater portion of the facade and continued to promote the theater’s films. In 1960, the venue now known as DeMille Theatre premiered Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho in June and Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus in October.

The grand movie palace lost its luster by the 1970s, as Times Square entered its notoriously gritty period. In 1976, it was split into three separate, narrow spaces and re-branded as the Mark I,II,III triplex. Guild Enterprises took over in the following year and renamed it Embassy 2,3,4. By that time, the corner billboard was expanded again and switched to displaying third party advertisements. Its minimalist Panasonic banner was a Times Square icon starting in the 1980s. Two more large spectaculars were added on the flanks.

701 Seventh Avenue circa 1994. Image from cinematreasures.org

In 1997, the theater was renamed yet again as Embassy 1,2,3, but its projectors went dark for good at the turn of the millennium. The corner spectacular was segmented into four separate billboards. By 2007, the former theater was rented out to tenants that included the Sbarro Pizzeria at the corner, Famous Dave’s Bar-B-Que, and a variety of souvenir shops such as the Phantom of Broadway.

701 Seventh Avenue around the turn of the millennium. The original Beaux Arts façade is in the upper right, Art Deco is in the center and upper left, and the new theater entrance and retail on the ground level. Image from the New York Tours By Gary blog

The phantom of Mayfair still lingered within surviving Art Deco motifs like railings, wall ornaments, and lavish ceilings.

Ceiling in the Phantom of Broadway souvenir shop. Images from Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York blog

Ceiling in Famous Dave’s Bar-B-Que. Image from the Gotham Lost & Found blog

Meanwhile, the square transformed even more dramatically than the old theater building. The Giuliani and Bloomberg eras replaced the grit and sleaze with more family-friendly, tourist-oriented destinations. In front of 701 Seventh, the 1973 TKTS booth, a discount vendor of Broadway show tickets, was rebuilt as the now-iconic red bleacher structure in 2006. By 2009, new pedestrian plazas further boosted the square’s capacity. The Times Square Alliance’s pedestrian count reveals it as the world’s most visited destination, with 300,000 to half a million visitors per day. Annual revenue from local businesses reaches $4.8 billion and accounts for nearly a quarter of the city’s tourist economy. Over the past 15 years, the ground floor rent at the centrally located Bow Tie Building has doubled to $2,500 per square foot, forcing what was once the world’s largest toy store to close just 14 years after opening.

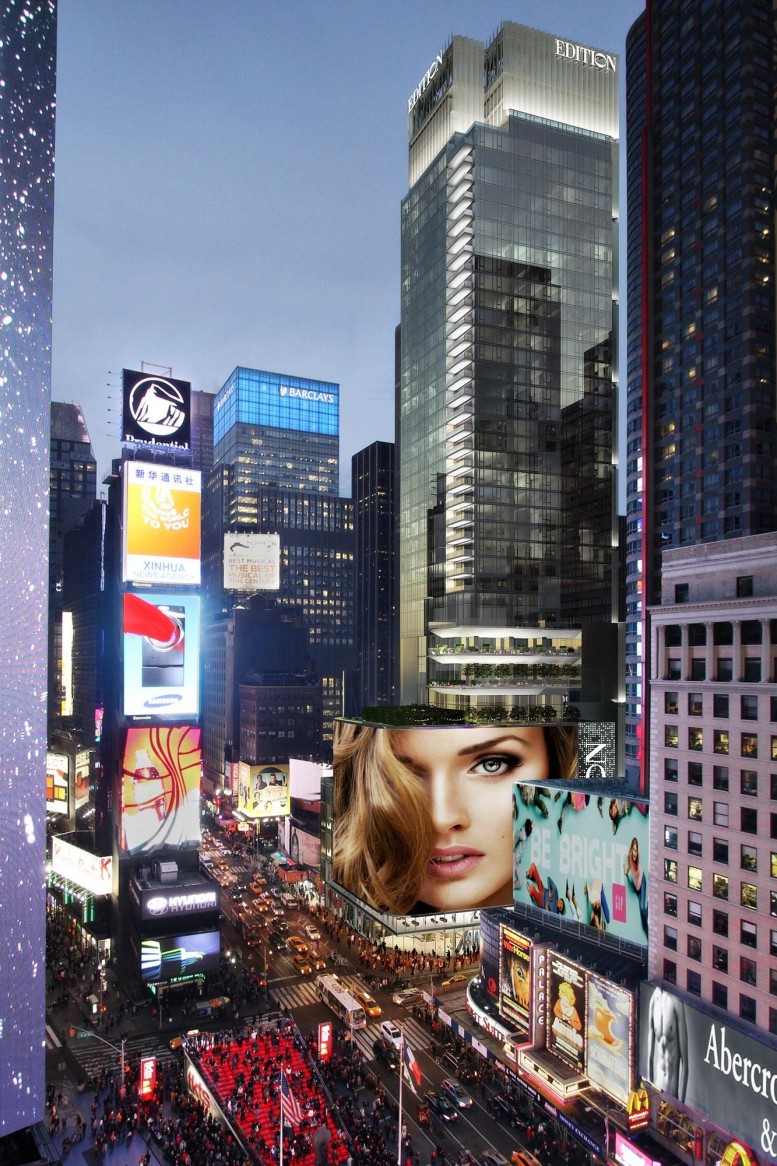

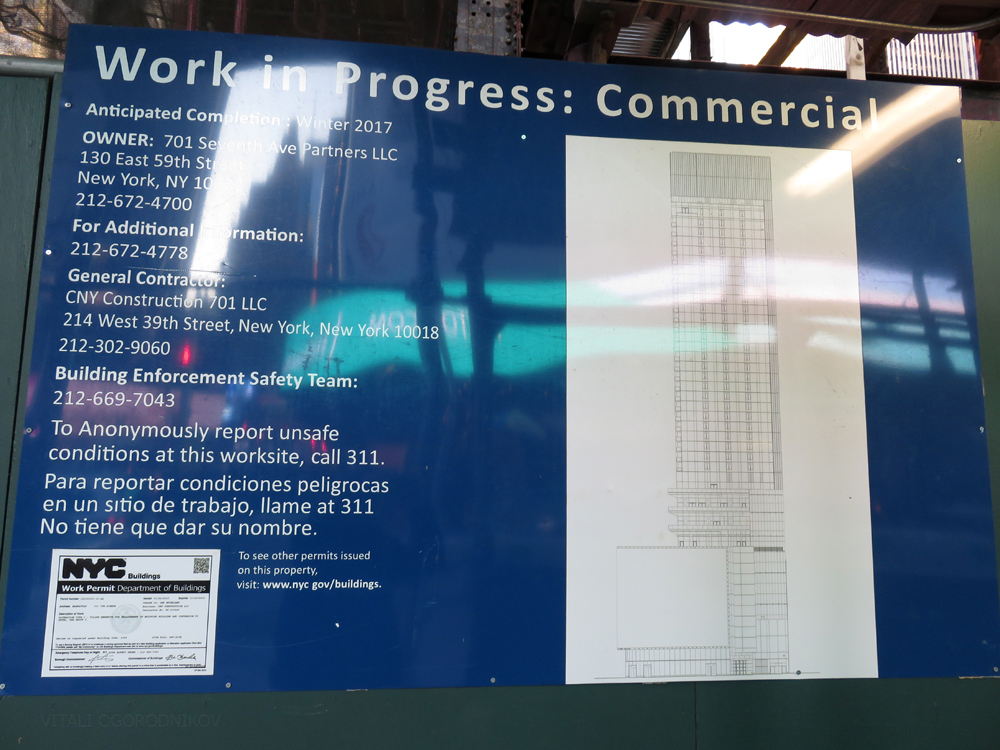

Over its century of existence, the Beaux Arts façade was altered almost beyond the point of recognition, while the once-grand theater inside became a mutilated shell, but the most dramatic change was yet to come. In late 2012, Maefield Development, Infinity Urban Century, The Witkoff Group, and Vector Group LTD’s New Valley unit purchased the building for $430 million. In its place, the 452-room Marriott Edition hotel, designed by PBDW Architects, would stack 39 stories about 500 feet high and feature 76,000 square feet of retail at the base. The old building’s century-long trend of ever-growing billboards would be taken to the point of singularity. An 18,000-LED spectacular will cover virtually the entire base, wrapping around the square-facing corner in a gentle curve much like its predecessor. The base roughly follows the massing of the old theater, with a green terrace set in front of the set-back tower. Two more grand balconies will face the square above the terrace.

The new building will be considerably smaller than the 1,949 room Marriott Marquis just across the square, but at 39 stories and around 500 feet in height, it will be nearly as tall. The new screen will face its larger counterpart at the Marriott Marquis, where the block-long, 25,740-square foot LED display became the world’s largest high definition screen in late 2014.

701 Seventh Avenue. Rendering by PBDW Architects]

Famous Dave’s closed in May 2013, around the same time as the rest of the tenants left the building, as demolition began to reveal ads of yesteryear layered underneath. Most of the building was dismantled over the course of 2014 and 2015. By the time Mayor Bill de Blasio wielded the ceremonial shovel at the October 2015 groundbreaking, he stood within a 100-foot-deep pit.

Looking northeast from the intersection of 7th Avenue and west 47th Street. February 2016. Photo by the author

Even as the new tower is prepped for vertical ascent, the old theater refuses to fully leave its Times Square home. The L-shaped frame of the office floors will be incorporated into the new tower, possibly as a concession to Midtown’s quirky zoning where larger footage is permitted if a portion of the old building is retained. Stripped of its billboard garments and stone skin, the steel skeleton is shrouded in a cape of black netting that gently billows in the wind. The rusted phantom awaits its reincarnation in the next chapter of the story that unfolds at the Crossroads of the World.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

Excellent story , well done .

This is a great feature especially with the pictures spanning all these years

Another fine and enjoyable article by Yimby. This explains what I’ve been seeing at the corner and what is yet to come.

Excellent article. Thank you!

Great Article. My family has lived in Hell’s Kitchen for 5 generations so I’m sure they were around to see the former incarnations of this building. Thank you.

None of the links work.

Thanks for the heads up, George. I fixed the error and they should work fine now.

Also, thanks for the positive feedback, guys.

Interesting article – thank you.

wonderful article. wondering whether they saved any of the beaux-art facade.

One of your best posts yet!

BROVO, Vitali Ogorodnikov. I have thoroughly enjoyed this insightful article. Thoughtfully illustrated with both vintage and contemporary photographs.

Please more in-depth articles like this, YIMBY. Thank You.