On Tuesday, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held public hearings on six proposed designations. One was for a complex in East New York, Brooklyn and the latter five were for properties in Midtown East.

The Brooklyn one came first and will be addressed first here. It is the former Empire State Diary Company buildings, located at 2840 Atlantic Avenue (a.k.a. 2840-2844 Atlantic Avenue) and at 181-185 Schenk Avenue. The former was designed by Theobald Engelhardt between 1906 and 1907 and the latter by Otto Strack between 1914 and 1915. The property was calendared on March 8 of this year.

Two tile mosaics by Leon Solon are featured prominently, and the architectural styles utilized are Renaissance/Romanesque Revival and Abstracted Classicist. The Borden dairy company took over the complex from 1924 to 1982, when dairy production ceased.

Land use attorney Valerie Campbell, of the firm Kramer Levin and representing site owner LSC, testified in opposition to designation. She said there has been “significant and unsympathetic alteration” over the years. She also said there is contamination from a 5,000-gallon heating oil tank.

The Historic Districts Council’s Kelly Carroll presented extensive and informative testimony in support of designation.

“The Empire State Dairy Company building is an unusually ornamented industrial building whose equal is not found anywhere. According to experts, these murals are the largest, extant majolica tile panels created by the American Encaustic Tiling Company. The murals, now over a century old, depict a bucolic Alpine scene in which a woman leads a cow and a calf to water; on the other, a man leads a bull to water. The people proudly display their animals within a sun-drenched, lush landscape of water, meadows, pines and mountains, harkening to the agrarian beginnings of the dairy industry. It is likely that the architect Otto Strack was paying homage to his country of birth, Germany, and that the rare Secessionist application employed here was inspired by Strack’s studies in Vienna.

“The first building constructed as a part of this complex dates to 1907, and was designed jointly by Otto Strack and Theobald Engelhardt. Mr. Engelhardt was a prolific Brooklyn architect of German-born parents, whose architectural legacy is inextricably intertwined with the former German communities and brewing industries in Brooklyn. How Strack wound up on this commission is a mystery, as he was a prominent brewery architect in far-away Milwaukee. It is quite possible that the common link of the brewery industry made these two German architects cross paths and eventually led them to build together this once in Brooklyn. Overall, this building is a rare example of architectural style and artistic aesthetic, and emblematic of the burgeoning industry in East New York in the early twentieth century.

“Moving forward, it is absolutely paramount that LPC move to calendar more significant buildings in East New York. This old neighborhood will soon fall victim to a pioneering paradigm, and if its heritage is not protected, there will be nothing left in the wake of rezoning. These especially include links to the neighborhood’s long-time civic presence in the forms of the East New York Magistrates Court and the 75th Police Precinct. Interestingly, both of these buildings have counterparts by the same architects in Sunset Park, though both buildings in Sunset Park are individual landmarks and those in East New York remain unprotected. To continue to ignore the set in East New York would communicate quite clearly that this community deserves less than another in Brooklyn. Further candidates that anchor the neighborhood include the Holy Trinity Russian Orthodox Church and the Vienna flats building at 2883 Atlantic Avenue. As revived, landmarked neighborhoods in Brooklyn testify: historic building stock is vital to the enrichment, pride and prosperity of a community, especially when that community is being built from the ground up.”

The designation also garnered the support of Alex Herrera of the New York Landmarks Conservancy, Friends of Terra Cotta, Preserving East New York (PENY), and an art historian who focused his testimony on the murals. “Preservation protects our communities,” said a PENY’s Zulmilena Then, who came clad in a print of one of the murals.

The commissioners didn’t make comments or vote on the designation. They plan to do that on September 13.

Up next were five items from the commission’s Great East Midtown Initiative. In May, the LPC added seven properties to its existing roster of five sites in the Midtown East area calendared for designation. It was those five previously calendared sites which received a public hearing on Tuesday. All five are from what the commission has deemed the Grand Central Terminal City Era.

The first was the Pershing Square Building at 125 Park Avenue (a.k.a. 101-105 East 41st Street, 100-108 East 42nd Street, 117-123 Park Avenue, and 127-131 Park Avenue). It was designed by John Sloan, along with the firm of York & Sawyer, and built between 1921 and 1923. The site had been formerly been occupied by the Grand Union Hotel.

The Pershing Square Building was the last tall building constructed without the setbacks mandated by law following the construction of the Equitable Building in the Financial District. It features large arched windows in the base along with more arched windows near the top. It was key to the functioning of the entire mass transit concept for Grand Central, as it helped connect different subway lines. It also features special subway entrances and direct access to the train terminal.

Several representatives of or people speaking on behalf of owner SL Green testified in opposition to designation, citing structural issues in the building and complications designation would present when it comes to upgrading the subway infrastructure below the building. That includes the Riders Alliance, the Grand Central Partnership, and the Association for a Better New York.

Columbia University professor Vishaan Chakrabarti spoke to those issues.

“I am Vishaan Chakrabarti, an architect, professor and an advisor to SL Green. I am also an ardent advocate of New York City landmarks in general and of the prerogatives of this Commission in particular. As I have stated repeatedly and publicly, this Commission is not only the the guardian of our past, it is the guardian of the future of our past.

“It is for this very reason that I implore you today to hold off on the landmarking of 125 Park Avenue. I have carefully reviewed your own detailed designation report and the structural of the building as it relates to the transportation network below it. This has led me to the unavoidable conclusion that landmarking this building, without further study could hobble the southern half of the Grand Central transportation hub in perpetuity, particularly as it relates to Midtown South and the resurgent adaptive reuse of the many historic structures that constitute this burgeoning technology and office hub.

“The entrances to the subways at Grand Central south of 42nd Street, to use a technical term, are “facacta .” They are narrow, dank, congested, confusing, and are arguably the worst part of Grand Central. Yet consider what they service: all of Midtown South, a submarket with one of the lowest vacancy rates in the nation, with new technology and finance companies that have reinvigorated a host of historic structures. It is a hot bed for so-called TAMI (Technology, Advertising Media Information) tenants; most notably, for example, Facebook has recently continued its massive expansion in the neighborhood with over 600,000sf. Even my office occupies a massive 2,000sf there!

“Vacancy in the submarket has decreased 30% over the last decade, and overall inventory has increased over that same period to 67 mm sf. But most relevant in this setting, this neighborhood is home to over 59 landmark structures and interiors.

“Ironically Terminal City never anticipated this growth to the south. Cornelius Vanderbilt controlled land predominantly to the north of Grand Central, along Park Avenue. While the Terminal proudly fronts on 42nd Street, it was never conceptualized to serve an office market to its southern flank, and yet that office market has emerged along Park Avenue to the south, through Madison Square Park, all the way to 23rd Street.

“This historic tech-ecosystem is indeed successful, but it is also FRAGILE . These companies can move elsewhere – and if they do, what will be the fate of the many landmarks in the area?

“The reality is that Midtown South thrives off the adjacency of Grand Central and its subways, yet that adjacency is nearing a choke point. It would be ludicrous to direct pedestrians from the south to the north side of 42nd Street given the addition of East Side Access, new growth in Midtown East, and an already congested set of entrances to the north.

“In studying 125 Park, the reasons the connections to the south are so poor become clear. The foundations for the building, as your designation report points out, were built simultaneously with the subway station, a decade before the building was built. Over 25% of the platforms of the 4,5,6 reside under the building, similar to the manner in which Madison Square Garden sits with its columns directly above Penn Station. The ensuing underground labyrinth makes the southern half of the subway station unnavigable, unsafe, and unappealing. As a representative of Stantec Engineering will describe after me, the only way to fix the situation is to rebuild the southern half of the station and deal with the foundations of this building.

“I’m sure advocates will come before you and say that we should not have to choose between transit mprovements and landmarks, a point of view to which I am sympathetic.

“However, this is a unique situation: even if the government had the public funds to fix the problem at this location, it could not do so without radically changing the structure of 125 Park. This is not, therefore, a debate about whether critical future transit improvements should come from the private sector or the public sector. The improvements are impossible without re-conceiving the building, regardless of who does the re-conceiving. This is not to say that the building does not have its architectural merits. It does, of course, although as the Commission has stated in the past, those merits are secondary to other area landmarks. In fact, what your own designation report makes clear is that the only constant at this site has been change.

“Commissioners, New York City is at a challenging point in its history. We have the great good fortune of continued growth, of new industries and entrepreneurs who want to live and work in our city, want to breath life into historic buildings, and want to use mass transit to get to work in a manner that is globally sustainable, with a lower carbon footprint than most growing parts of the world. In an historic, aging city such as ours, new growth brings difficult challenges that you reckon with every day, an act for which we thank you immensely.

“But the balance to be struck here is not between growth and preservation at a single site as is so often the argument. The livelihood of an entire historic neighborhood hangs in the balance, the preservation of which requires a holistic view and earnest deliberation. It is for this reason that we ask that a hold be placed on any landmarking action at 125 Park, pending further study by the MTA, the building owners, the civic community, and of course this Commission.

“Thank you for the opportunity to speak.”

“[The building] was old fashioned even before it was finished,” Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY) vice president Paimaan Lodhi said. “This building did not attract the attention of the authors of the AIA guide nor is it a must see architectural icon of New York City, such as the Chrysler Building.”

Herrera, on the other hand, supported designation, saying the lack thereof had been an “oversight.” Christabel Gough of the Society for the Architecture of the City spoke of the building’s fantasy elements, including arches that look like they came from Italy.

The HDC’s Zay delivered testimony on the overall Greater East Midtown Initiative.

“Since the summer of 2012, exactly four years ago, HDC has been both monitoring the East Midtown Rezoning initiative and actively advocating for protection of its finest buildings, those that best exemplify the area’s history and stages of development. The Commissioners may be aware that in January 2013, HDC submitted RFEs for 33 properties in the rezoning area. In the spring of that same year, the LPC submitted its own list as part of the Environmental Impact Statement for the rezoning. That list, coincidentally, also included 33 buildings. Some of the LPC’s 33 buildings overlapped with HDC’s 33 buildings, so when combined, they represent a group of 45 landmark-worthy buildings. In May of this year, the LPC put 12 of these on its calendar. While we were thrilled to see some move toward a more certain future, we remain concerned for those that have been left out. We have distributed copies of RFEs for those neglected buildings so that the Commissioners may consider them. Even more coincidentally, there are 33 of them!

“Within the categories laid out by the LPC: ‘pre-Grand Central Terminal’, ‘Terminal City’, and ‘post-Grand Central Terminal’, only one building that was calendared was constructed after 1929, and that one building dates to 1977, leaving a nearly 50-year gap in the story of East Midtown. Even though a group of magnificent mid-century office buildings – one of the neighborhood’s hallmark building types – was included in the LPC’s (and HDC’s) list, none of them are moving forward in this round of considerations for landmark status. These many overlooked gems include the Former Girl Scouts of America Headquarters at 830 Third Avenue, the Union Carbide Corporation Headquarters at 270 Park Avenue and the Universal Pictures Building at 445 Park Avenue – all important works of Modern architecture by sophisticated architects for a new wave of corporate clients in post-World War II New York.

“The 12 items placed on the LPC calendar represent just the tip of the iceberg in terms of meritorious architecture in East Midtown, but we are pleased to testify today in favor of the swift designation of the first five of these.”

Then HDC’s Kelly Carroll delivered testimony specific to 125 Park Avenue, going off-script to start, saying landmark designation is not an impediment to growth or mass transit upgrades.

“With its foundations laid in 1914, two years before the enactment of the 1916 Zoning Resolution, the Pershing Square Building was an anomaly for new buildings at the time of its completion nine years later, in 1923. As The New York Times reported one year before it opened, the Pershing Square building ‘will be unique among recent New York office structures, being designed without setbacks…’ By 1923, office buildings in New York City were forced into a system of skyscraper design employing setbacks for increased height,” Carroll said as she returned to her prepared remarks. “At 24 stories, the Pershing Square Building was the last tall building in the city to be completed in the form of a pre-World War I office building. As such, in 1923 it stood as a reminder of a previous era, and today it exhibits a maturity beyond its years.”

Tara Kelly of the Municipal Art Society also supported designation, with her own extensive testimony.

“Erected on the site of the former Grand Union Hotel, the Pershing Square Building was designed by John Sloan and completed in 1923. The 25-story Romanesque structure is clad in brick and terra cotta supplied by the Atlantic Terra Cotta Company. To help bring about the rugged hand-made texture of the façade, Sloan instructed the supplier to roughen they clay for kiln burning. At the fifth-floor level, the façade also features helmeted figures called war angels alluding to peace, among other aspirational concepts. The brickwork cladding is further ornamented by “guilloche patterns and cross-banded columns with inner band of leaf work,” as described by Christopher Gray in his Streetscapes column for the New York Times.

“In 1924, Sloan partnered with Robertson to open their architectural practice and lease a space in the Pershing Square Building. Together they are renowned for their early skyscraper designs, including the landmark Chanin Building and the soon-to-be-heard Graybar building.

“The Pershing Square Building makes a significant contribution to the East Midtown office district first established by Terminal City, and deserves individual landmark status.”

Designation of the Pershing Square Building also had the support of Manhattan Community Board 5 and preservation architect Lisa Easton.

LPC Chair Meenakshi Srinivasan did remark that infrastructure upgrades have often found a way to be implemented within the confines of preservation.

Graybar Building, from Graybar’s Twitter

The second Midtown East property was the Graybar Building, located at 420 Lexington Avenue. It was designed by Sloan & Robertson and built between 1925 and 1927. The 30-story structure is clad in brick and limestone, with amazing Art Deco features including multiple setbacks.

Robert Schiffer of owner SL Green said that both designation of the interior Graybar Passageway to Grand Central Terminal and the lack of incentive to demolish the building make designation unnecessary.

Gough called the building “legendary” and praised its “colossal and relatively unembellished façade.” She said it would help complete the preservation of what is left of Terminal City.

HDC’s Zay pointed out that it was the largest office building in the world at the time of its construction.

“Named for one of the original tenants, the Graybar electricity and electrical appliances company, the Graybar Building is a striking Art Deco office building designed by Sloan and Robertson and completed in 1927. Ornament is primarily restricted to the monumental bas-reliefs of the base thanks to developer John R. Todd’s preference for spending money on only the parts of the building that might impress potential tenants,” Zay testified. “When it was constructed, the 30-story building was said to be the largest office structure in the world. The New York Times compared the workforce of 12,000 that inhabited the building to a ‘small city.’ Although Graybar left in 1982 when the corporate headquarters were relocated to St. Louis, the name has held on. The building remains a fixture in the East Midtown neighborhood.”

Kelly spoke of the project’s integration into the neighborhood, its 30 setbacks, and more.

“The Graybar Building was constructed along Lexington Avenue on the lot immediately to the south of the Grand Central Post Office. It is integrated into the surrounding properties, adjoined by Grand Central Terminal to the west, the former Commodore Hotel (now Grand Hyatt) to the south, and the post office to the north. When it opened, the Graybar was the largest office building in the world, housing 12,000 workers in 1.2 million square feet of office space, and featured direct access to Grand Central Terminal.

“Designed by Sloan & Robertson, the U-shaped plan consists of thirty setback stories faced in buff-colored brick above a limestone base. A wide light court faces Lexington Avenue, allowing for light and air to reach most offices. The building’s three limestone entrance façades are decorated to the north and south with Deco-Assyrian bas-reliefs, and in the center with an allegorical relief representing Transportation & Electricity. The southern entrance features a canopy above each of three doors. The central marquee is held in place by three poles that mimic the mooring lines of a ship with conical vermin baffles and rats depicted climbing the lines. Where anchored to the building, the steel bars emanate from decorative rosettes formed by rat heads. The side canopies are supported by rods anchored in the mouths of gargoyles.

“Above the limestone base, decorative elements are few. Developer John R. Todd built high quality buildings that, while well-made, met only a minimum standard to compete in the marketplace. At Graybar, Todd accepted ornamentation at the ground level “to impress prospective tenants” while forcing Sloan & Robertson to eliminate decoration from the top of the building – a location where Todd felt no one would appreciate the detail, and was therefore not worth the cost.

“Literally connected to Grand Central, the Graybar Building is a key feature of Terminal City and should be dually protected with the same care by the Landmarks Preservation Commission.”

Designation of the Graybar Building was also supported by the Art Deco Society of New York (represented by Lisa Easton), the New York Landmarks Conservancy’s Alex Herrera, who called it “highly intact,” and a representative of Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, who spoke of the need for “a mix of building types.”

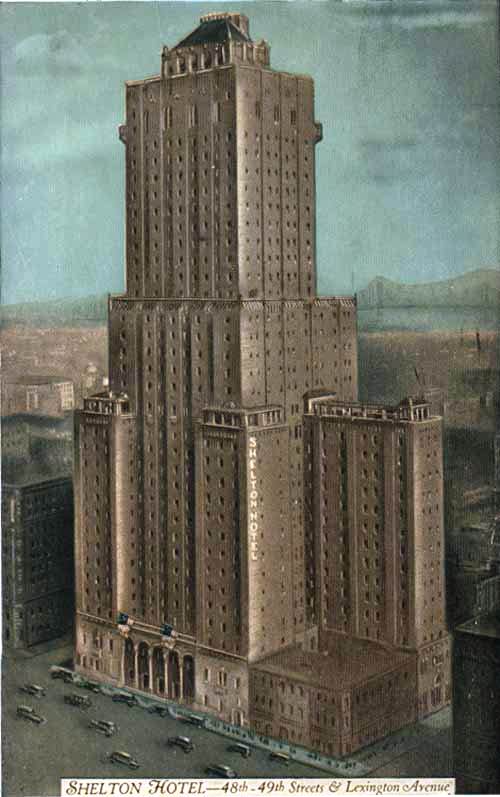

Shelton Hotel, from Daytonian in Manhattan

The third Midtown East item was the former Shelton Hotel at 525 Lexington Avenue (a.k.a. 523-527 Lexington Avenue, 137-139 East 48th Street, and 136-140 East 49th Street). It was designed by Arthur Loomis Harmon and built between 1922 and 1924. It’s an early example of a skyscraper residential building. It was later the Halloran House Hotel and is now the New York Marriott East Side.

Owner Brett Madison, unsurprisingly, testified against designation.

Manhattan Community Board 6’s Gary Papush, on the other hand, along with Herrera, did support designation. Herrera lauded its “rich and interesting history.”

Zay’s testimony spoke about some of that history.

“The Shelton was one of the most heralded buildings of the 1920s and is the first great monument to New York City’s 1916 zoning code. Critic George S. Chappell exulted architect Arthur Loomis Harmon’s ‘romantic and thrilling achievement’; it was such a striking presence on the New York skyline that it inspired a series of masterful paintings by artist Georgia O’Keeffe. The building was commissioned by James T. Lee, a prominent New York builder, also responsible for such luxury apartment buildings as 740 Park Avenue and 998 Fifth Avenue.

“In 1916, New York had passed America’s first zoning law, mandating setbacks on skyscrapers in order to ensure that light and air would reach the street. Harmon’s design for the Shelton was one of the first to prove that a building of great expressive strength could be designed within the zoning rules, with the required setbacks and tower occupying only twenty-five percent of the lot area. From a limestone base with double-height arcade, richly ornamented with carved detail, the building soars upward with a series of beautifully integrated masses with no cornices to block the continuous vertical thrust. From Lexington Avenue, the building appears as a rectangular block, but the structure is actually U-shaped in plan, with a light court at the rear, facing east. The brick of the upper stories is rendered like a textile with some bricks pulled out to create texture. The emphatic verticality lends a certain Gothic character to the building, but the use of materials and details harks back to Byzantine and Italian Romanesque forms, reflecting the architect’s intentions ‘to take from any source whatever was required, treating it in a free and easy classical way, the hope being that the details and masses shall both suggest, if possible their own time rather than that of their prototypes.’(This quote was taken from an article Chappell wrote for The New Republic in 1924 entitled ‘The Shelton’.)

“The Shelton was planned as a ‘club hotel’; i.e., a residential hotel for men, with such club features as a swimming pool, Turkish bath, billiard room, bowling alley, and, on the setbacks, rooftop gardens. Male athletes carved above the column capitals at the entrance symbolize its original function. The residential men’s hotel was not a success, however, so the hotel became a more traditional residential and transient facility soon after its completion. The design, however, was deemed a great success. It was widely admired by architectural critics and received gold medals from the American Institute of Architects and the Architectural League of New York. Although the interior was gutted in 1977, the exterior was restored for its conversion into the Halloran House Hotel.’”

Kelly’s testimony for MAS also explored some of that history.

“The Shelton Hotel, now the Marriot East Side, was built in 1923 and designed by Arthur Loomis Harmon. Aside from being the tallest building at the time, it is also the first hotel to fully implement the 1916 Zoning Resolution.

“Prior to his work on the Shelton Hotel, architect Arthur Loomis Harmon (1878 – 1958) had designed the Allerton House at 145 E 39 Street, constructed from 1916-1918. Built just before the new zoning laws came into effect, Harmon emphasized the vertical by recessing the window bays, but the massing still prioritized bulk over height.

“Harmon’s skyward vision was not fully realized until the construction of the Shelton Hotel, where the implementation of the 1916 zoning resolution allowed for further emphasis of vertical expression. The 34-story tower is supported by a limestone base, where the front entrance is defined by a shallow loggia supported by six Corinthian columns. Above the ground floor, the rusticated brick façade reflects Romanesque, Byzantine, and other Medieval styles, with limestone returning to clad each setback. Assorted gargoyles and other sculptural ornamentation playfully protrude above entrances and punctuate the facade.

“Notable tenants of the Shelton were painter Georgia O’Keefe and her husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz, for whom the Shelton served as a vantage point to capture the city in paint and picture. O’Keefe crafted fifteen cityscapes from their balcony view, and Stieglitz’ photographs include “From the Shelton, Looking Northwest,” showing a partially built Waldorf-Astoria.

“The Shelton Hotel is considered Harmon’s best-known individual work, receiving awards from the Architectural League of New York and the American Institute of Architects. It was lauded by critics including Lewis Mumford, who called it “buoyant, mobile, serene, like a Zeppelin under a clear sky.” In 1929, Harmon became a partner in the newly renamed Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, who were later responsible for the design of the Empire State Building.

“In sum, the Shelton is one of the most prominent and innovative Terminal City hotels, designed by a distinguished architect, home to significant 20th century artists, and thus merits recognition by the Landmarks Preservation Commission.”

Beverly Hotel, image from the HDC

Up next was the former Beverly Hotel (now the Benjamin Hotel), located at 125 East 50th Street (a.k.a. 125-129 East 50h Street and 557-565 Lexington Avenue). The 30-story building was designed by Emery Roth with Sylvan Bien and built in 1926.

Land use attorney Valerie Campbell, speaking for the hotel’s owner, said that designation would present financial and operational burdens. She also noted that the principal street façade has been heavily altered and is now a modern recreation. The hotel’s owner said that, among other things, designation, specifically its application to the windows, would prevent reconfiguration of the hotel rooms.

Zay’s testimony spoke to the structure’s originally planned use, and its history from there.

“Planned as an apartment hotel for both transient and long-term guests, the thirty-story Beverly was designed in the eclectic pseudo-Renaissance manner favored by Emery Roth, whom the authors of New York 1930 describe as ‘the unquestioned master of the luxury residential skyscraper.’ Built in 1926-27, the hotel is dramatically massed, with a fourteen-story base topped by a series of dramatic setbacks, reminiscent of an Italian hill town, culminating in a three-story octagonal tower. The massing included many setbacks that were designed as roof gardens, accessible through French doors. A writer for the Real Estate Record and Builders Guide placed the hotel within its original context, stating:

‘The Beverly is in keeping with the high class character of its neighbors and it will be notable for the latest design in modern architecture from the zoning viewpoint. The adoption of roof gardens at the setbacks while not a novelty for apartment houses has seldom been used where the multi-family house becomes a hotel. The height will make it one of the conspicuous skyscrapers in Mid-Manhattan.’

More than just interesting for its building envelope, the fashionable Beverly Hotel was touted in a mid-1930s subway advertisement as ‘New York’s Smartest’ place featuring ‘Music, Special Facilities for Private Parties’ with ‘Luncheons from 75 cents, Dinners from $1, Cocktails from 30 cents, also A La Carte French Cuisine.’ all available in the Duplex Cocktail Lounge. Not to plan projects in other people’s buildings, but that would be one restoration which, prima facie, the Historic Districts Council could heartily endorse.”

Kelly talked about the building’s place on “Hotel Alley.”

“Built in 1927, the Beverly Hotel was commissioned by Moses Ginsberg to host middle-income visitors to New York City. The 28-story hotel boasts an attractive two-story limestone base, ornamented by terra cotta relief. The upper stories, clad in brick, set back to culminate in an octagonal clock tower.

“The neo-Romanesque design results from a limited partnership between Emery Roth and Sylvan Bien. Hungarian born, Roth was employed by America’s finest Beaux-Arts architecture firms of the time, including Burnham & Root, Richard Morris Hunt, and Ogden Codman, before striking out on his own. His first major commission was the Hotel Belleclaire. He later solidified his reputation for luxury residential skyscrapers with the Ritz Tower, the San Remo Apartments, the Beresford, and the El Dorado Apartments (all individual New York City landmarks). Meanwhile, Sylvan Bien teamed up again with Ginsberg for his best-known project, the Hotel Carlyle, located in the heart of the Upper East Side Historic District.

“An important contribution to Terminal City’s ‘hotel alley,’ the Beverly Hotel warrants designation as an individual New York City landmark.”

Designation also has the support of Herrera and Papush.

The Lexington, image via HDC

Finally, there was the Hotel Lexington, located at 511 Lexington Avenue (a.k.a. 509-515 Lexington Avenue and 134-142 East 48th Street). It was designed by the firm of Schultze & Weaver and built between 1928 and 1929.

Bill Tennis of owner DiamondRock Hospitality Company testified against designation, saying that a lot of the building’s original parts are gone.

Zay’s testimony spoke to the record of the design firm.

“Schultze & Weaver, a firm that specialized in skyscraper hotels, not only designed the Lexington, but also the Waldorf-Astoria, the Sherry-Netherland and the Pierre in New York, and the famous Biltmore Hotels in Los Angeles and Coral Gables, Florida, and the Breakers in Palm Beach. For the Lexington, the architects designed a massive structure with vertical window bays that accentuate the building’s height and draw the eye up through a series of setbacks to the pyramidal tower and crowning lantern. T-Square, the architecture critic of The New Yorker, found this dramatically massed hotel to be a “romantic addition” to the Lexington Avenue skyline. The Lexington Avenue entrance to the hotel is through a beautifully-carved, limestone arch in a Romanesque-inspired style. The original exterior arch is now inside glass doors, but retains its classically-garbed figures representing various professions. The restaurants at the Lexington were among the first to experiment with the European notion of replacing tips with a ten percent service charge added to all bills, an idea that never took hold in the United States. The Lexington opened on October 15, 1929, only fourteen days before the stock market crashed. Unfortunately, this hotel, which was planned to cater to middle-class tourists, soon failed and in 1932 was in the hands of a receiver. Fortunately, through a series of ownership changes, the hotel has continued in operation.”

So did Kelly’s testimony.

“The Hotel Lexington was designed by Schultze & Weaver and completed in 1929 on the corner of East 48th Street and Lexington Avenue. The Art Deco/neo-Romanesque hotel stands 26 stories, clad in limestone and brick, and marked by tiered setbacks, a result of the 1916 zoning resolution.

“Working with Warren & Wetmore, Leonard Schultze was the chief of design for Grand Central Terminal from 1903 to 1911. Together with Spencer Weaver, the firm was responsible for such notable luxury New York hotels as the Sherry-Netherland, the Pierre, the Park Lane, and the Waldorf-Astoria. Farther afield, the duo designed the Breakers in Palm Beach, the Atlanta Biltmore, the Los Angeles Biltmore and the Sevilla Biltmore in Havana.

“Another substantial contributor to Terminal City’s ‘hotel alley,’ the Hotel Lexington is deserving of individual landmark status.”

Other than Chair Srinivasan’s brief remark on the Pershing Square Building, none of the commissioners made any remarks. The other Midtown East items will receive public hearings later in the year and the commission hopes to vote on all 12 by the end of 2016.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

Photos before details as well, very long I must read about one hour for my understand.

Contrary to the comments of the comment below, I found the detail (and the history) helpful. Thank you.