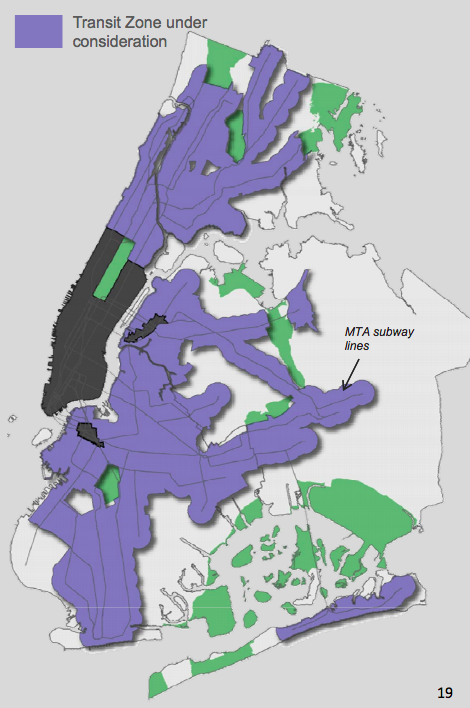

A few weeks ago, the Department of City Planning announced its intention to tweak the city’s zoning rules to encourage the production of affordable housing. The most important change is a reduction in the city’s parking requirements, which up until now have required off-street parking throughout virtually all of the outer boroughs and Upper Manhattan – generally around one space for every two units, with exemptions for small buildings.

The requirement for developers in dense, transit-oriented neighborhoods to provide expensive parking spaces will, however, only be waived for those building subsidized housing units. All market-rate apartments – the vast majority of new construction in the city – will still need parking, with a discretionary exemption for the unsubsidized units in buildings that have set aside some units to be rented at below-market rates.

In isolation, this is a good thing – parking is an unnecessary luxury in a city as dense and costly as New York, and the requirements are especially absurd when taxpayers are footing the bill and the tenants are relatively poor.

But given the politics of affordable housing in New York City, the move also has the unfortunate side effect of ensuring a fight down the road between affordable housing advocates and those supporting more general parking reform.

Assuming City Council approves the measures, it would add parking relief to the list of benefits that developers get in exchange for building affordable housing (a tax abatement and sometimes a meager density boost are the others). But just like the tax abatement doesn’t incentivize 80/20 buildings beyond the gentrifying fringe, where all new buildings get a tax break, so too would the parking benefit disappear if reform was passed more broadly.

This would make private developers building on land already entitled for development marginally less likely to include below-market units. It’s therefore logical to assume that affordable housing interests – politicians and advocates whose sole goal is the production of subsidized units, and who are indifferent to New Yorkers who rent and buy on the market – might oppose reform for purely market-rate projects.

The de Blasio administration essentially denied the dynamic to Streetsblog:

This provision is designed not to offer the carrot of lower parking minimums in exchange for adding affordable units to a market-rate development, but to simply improve the balance sheet for mixed-income projects. “It’s not bargaining for affordable units,” said Eric Kober, director of housing, economic and infrastructure planning at DCP. “It’s really a matter of enabling the city to use its affordable housing resources as efficiently as we possibly can.”

The provision might not be designed as a carrot to developers, but when not applied to all units, it nevertheless is one.

Brooklyn councilman Stephen Levin certainly realized this a few years ago along with Tish James, then a councilwoman and now the city’s public advocate. The Bloomberg administration proposed cutting the minimum requirements in downtown Brooklyn in half for market-rate buildings, and entirely for affordable project – something that didn’t sit right with James or Levin, who seemed not to want any reduction at all for purely market-rate projects.

And the local community board in East Harlem wanted the developer of a pair of towers at 125th Street and Park Avenue to include more subsidized units in exchange for providing less parking than required (they settled for more retail, to provide jobs to those in the community).

And New York City isn’t the only place where affordable housing advocates have tried to use parking as a bargaining chip with developers. When California was considering limits on how much parking cities could require, the Southern California Association of Nonprofit Housing opposed the measure (which didn’t pass).

“We have 30 years of history with density bonus law that recognizes the value of trading a planning concession, whether it be height, density, or parking for supplying the mix of incomes in a project,” policy director Lisa Payne told the California Planning & Development Report. “This bill would have removed that tool.”

Just like Tish James told Streetsblog that she didn’t see the affordability benefit to lower parking requirements for market-rate buildings (“I’m not naïve enough to think that savings will be passed along to buyers or renters”), a policy director for a different affordable housing advocacy “questioned whether those savings would be passed on to residents.”

(Both, of course, misunderstand the mechanism by which costs are passed on. It isn’t developers currently building who would pass on the lower costs, but would-be builders in more marginal areas where projects wouldn’t pencil out with parking, and the effect this greater supply has on the overall market.)

But such is the cost a housing policy with a narrow focus on maximizing subsidized housing production. The glimmer of hope is that while the California attempt at parking reform was defeated, neither the downtown Brooklyn council members nor the East Harlem community board members were successful in their attempts to tie rational parking policy to what should be an unrelated topic – subsidized housing. Hopefully rising hostility to market-rate development will not overcome any attempts at parking reform that may come.

Talk about this topic on the YIMBY Forums

For any questions, comments, or feedback, email [email protected]

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews