When a storm surge slammed into Aimann Youssef’s house on Midland Avenue in Staten Island during Hurricane Sandy, he was devastated. “Without the house, it’s like being without an identity,” he told YIMBY. “I lost my home, my cars, my business, everything.”

His home was one of dozens damaged by a 16-foot tidal surge in Midland Beach, where a handful of houses on each block remain empty.

As the flood waters rose, he used a long orange extension cord to rescue several strangers who had been swept out of their homes and cars. Then, he swam to safety at the house next door. The next morning, he pitched a relief tent in front of his ruined house, serving up hot meals and donated supplies to his displaced neighbors.

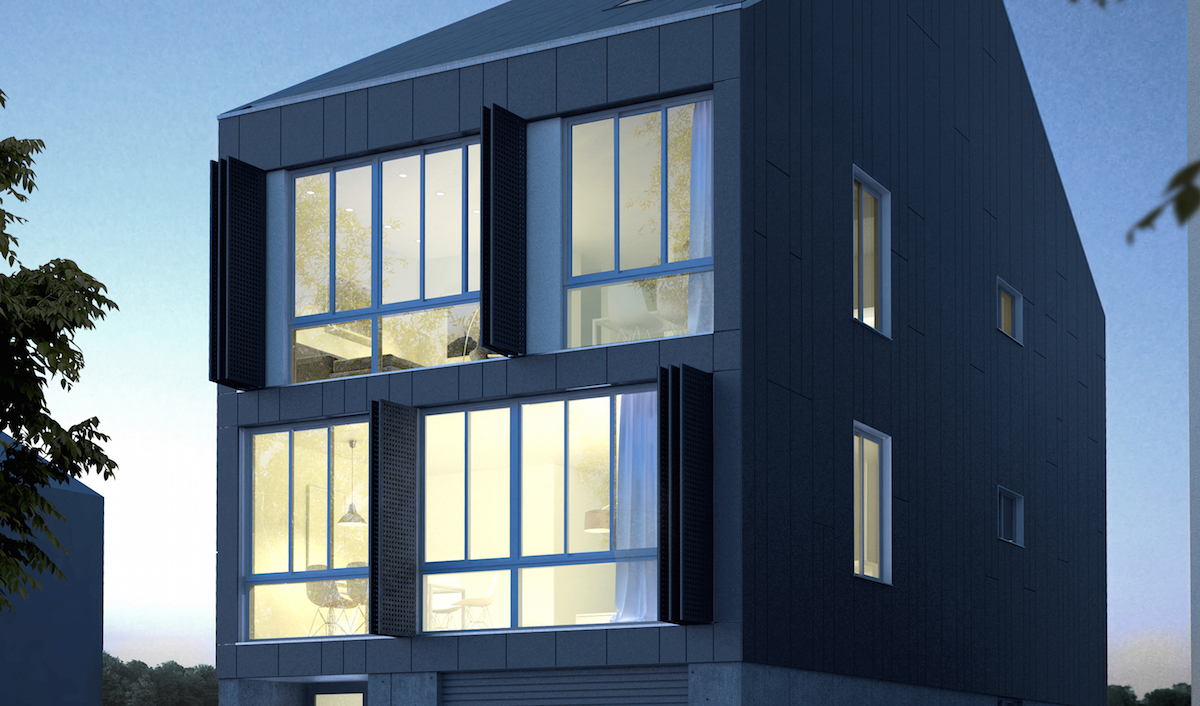

Nearly three years later, the 45-year-old Syrian immigrant is taking steps to rebuild his house at 481 Midland Avenue, even if he can barely afford it. Tribeca-based AB Architekten, headed by Alex Blakely, created a simple, modern design for the two-family home.

“The design, it’s so beautiful, and he’s not charging me for his work,” explained Youssef. “He’s doing it all from his heart.”

The three-and-a-half-story townhouse will have an upper duplex and a smaller garden apartment. Youssef will live upstairs, and his 81-year-old mother will occupy the lower unit.

In the wake of the hurricane, the city passed new building and zoning rules that create challenges for architects. Living space and mechanicals have to be elevated 10 feet above the ground, which could potentially create an anti-urban, uninviting block. To prevent that, Blakely and his team included a raised front yard and plantings, protected by concrete walls that rise several inches above the street.

The first floor will host a one-car garage and storage, because it can’t be considered living space under the new flood zoning. The facade will be clad in water-resistant fiber cement board panels, which are made of wood pulp and cement. Those same panels will also be perforated and used as retractable sun shades on the southern side of the house, facing the street. They’ll work as a rain screen and protect the windows when the next major storm hits. And a cutout on the attic level will become a terrace, offering attractive views of southern Brooklyn and the Rockaways.

The Department of Buildings will likely approve permits in the next few weeks, and Blakely hopes to start construction soon. There’s just one problem: Youssef doesn’t have any money to build it.

Over the last two years, Youssef has turned his relief tent into a non-profit, Half Table Man Disaster Relief. He says that whatever money he had has gone toward running a food pantry and travelling to volunteer in other places afflicted by natural disasters—Oklahoma, Alabama, Texas, and flood-prone towns in upstate New York.

He registered with the city’s Build It Back program in 2013. But like thousands of flood-battered New Yorkers, he hasn’t seen any sign of federal relief funds. 4,598 Staten Island homeowners registered with the program, and as of this writing, the city has only sent out 1,003 reimbursement checks. Construction has begun on 368 homes, and work on another 286 homes has already finished.

“I’m going to need lots of help to rebuild,” he said. “I have to start somewhere, even if it’s with the foundation. I hope I receive a check from God…I’m going to borrow $5,000 or $10,000 just to start.”

Meanwhile, hundreds of other Staten Islanders have given up on rebuilding in the 100-year flood plain. Instead they embraced a “managed retreat”—they’ve applied to sell their homes to the state and move elsewhere. But the buyout program has only benefited three neighborhoods: Oakwood Beach, Ocean Breeze and Graham Beach.

Three Staten Island city council members want the city to buy up the dozens of vacant homes in Youssef’s neighborhood, Midland Beach, as well as two other nearby communities, New Dorp Beach and South Beach.

“It is our understanding that some of these properties are unencumbered by mortgages, but the owners — having lacked the resources to pay for repairs and basic maintenance, property taxes, and increasing flood insurance premiums — have simply walked away,” the officials wrote in a letter this week to the city’s Office of Housing Recovery.

They’re asking the city to use Build It Back funding to purchase and redevelop the damaged properties. Banks won’t even foreclose on the houses, because the repairs cost more than they’re worth.

The buyouts have apparently taken less time than issuing checks for rebuild projects or repairs. The city has already demolished more than 50 homes in Oakwood Beach, where the community collectively decided to take a buyout from the state. Dozens more sit empty, waiting for the wrecking ball. Some properties will be redeveloped, but others will be returned to nature or used as parkland.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

a clean, forward thinking design.