This fall, a number of reports have emerged about the possibility of decking over and developing Sunnyside Yard, the Amtrak-owned facility wedged between between the Long Island City and Sunnyside neighborhoods in western Queens.

Amtrak has expressed interest most openly, with Chairman Anthony Coscia saying last month that the railroad was in talks with the de Blasio and Cuomo administrations about doing something with the 167-acre yard. YIMBY has also heard that the Economic Development Corporation is looking into development possibilities, and Queens’s Community Board 2 has asked Borough President Melinda Katz to study the issue.

While YIMBY will of course cheer on any project to build new homes in this housing-starved city, there are reasons to be skeptical that a deal will be reached. Between the cost of building a deck and the city and Amtrak’s competing interests in the site, developing the rail yard will likely leave many unsatisfied, if a plan can be agreed upon at all.

The most fundamental issue with the site is that the city will seek to maximize the number of affordable housing units built while Amtrak will seek to maximize the proceeds it can get from a sale or long-term lease (which it would, hopefully, pour back into the Northeast Corridor, where Amtrak wants to spend $151 billion on a high-speed rail plan, or at least a new tunnel beneath the Hudson).

These two goals are in direct opposition.

To see why, a reexamination of the deal struck at Atlantic Yards is in order. While the right to develop a very dense market-rate project above the Vanderbilt Rail Yard, on the edge of increasingly desirable downtown Brooklyn, might have been worth hundreds of millions of dollars to a developer, Forest City Ratner had to dangle a fairly large amount of subsidized housing to get everyone on board with the project. The result was a deal that was more favorable to affordable housing production than it was to the MTA’s finances.

As a result of the money-losing affordable housing that Forest City Ratner (and, now, its partners) agreed to build, the MTA only got $100 million out of the deal, plus a replacement yard worth $147 million. This was actually less than the original deal struck, as the $100 million in payments is now being drawn out over more than two decades, and the new infrastructure was cheapened by about $100 million.

Back at Sunnyside Yard, Amtrak might decide that acceding to the de Blasio administration’s likely demands for high affordability ratios will cut too deeply into the proceeds from any sale or lease, and that it would be better to hold onto the property until a more compliant mayor comes along. And the de Blasio administration might decide that doing battle with NIMBY forces and affordable housing advocates in order to advance Amtrak’s desire to develop the site with more profitable market-rate housing is just not worth it.

And any potential deal over Sunnyside Yard would have to reckon with another legacy of Atlantic Yards: its tremendous commercial failure.

The deal was struck as the market was on an upswing, but as with many large, complex, politically charged projects, development has dragged on long past the market prime, into the next real estate cycle. Last year, the Wall Street Journal reported that Forest City Ratner planned to take a write-down of $250 million to $350 million on the project, on top of the arena’s underwhelming financial performance.

While Atlantic Yards’s poor performance won’t cut into the affordable housing that Ratner has already agreed to (though it has delayed the delivery), those bidding on the right to build at Sunnyside Yard won’t forget it, and their bids will reflect the challenges of developing the site – political ones having to do with affordable housing and union demands, but also the high costs of development over an active rail yard.

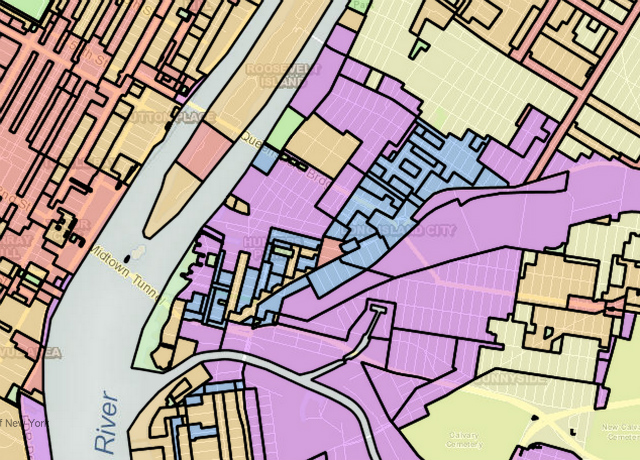

All of the land in purple is currently zoned for manufacturing, with only the street grid-less area to the west of the blue being part of the actual rail yard.

New York City has lots of development opportunities on terra firma, limited only by zoning. The part of Long Island City already zoned for dense development has underutilized manufacturing-zoned land to its north, south, and east (across the rail yard, in Sunnyside proper), plus low-density residential land that could be rezoned to its west. If affordable housing is the goal, it might be easier to focus on this lower-hanging fruit, and leave Sunnyside Yard for an administration more willing to accept market-rate development at the site.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews