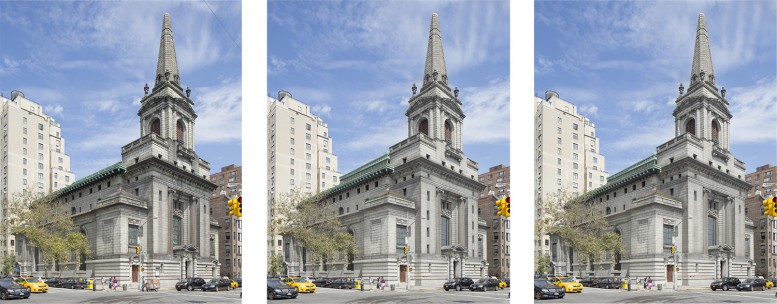

It was all the way back on March 11th that the Landmarks Preservation Commission approved controversial plans to convert the former First Church of Christ, Scientist in New York City, located at 361 Central Park West and West 96th Street, into 39 condominiums. But that wasn’t the last word. The battle went on in the community board, and it continued this week at the Board of Standards and Appeals (BSA), and will continue into 2016.

Before we get to the BSA situation, a bit about the situation at the community board. Following the LPC’s decision, Community Board 7’s Landmarks Committee calmly accepted the verdict, either satisfied with or resigned to the structural changes approved for the landmark, which was built in 1903. Then CB7’s Land Use Committee approved the change of use and zoning changes required for the conversion to go forward.

But that wasn’t the end of it. The full board voted against the project, reversing decisions by its committees. Of course, community boards don’t actually decide the fate of these projects, at least not officially since they are advisory bodies.

Who does have the last word on the project? Basically, it’s the Board of Standards and Appeals. That city agency, which doesn’t get as much press as the City Planning Commission or even the LPC, has to actually grant the zoning variances necessary for the conversion to actually happen. The latest in a series of hearings at the BSA

The owner, listed as 361 Central Park West LLC, wants the BSA to grant variances due to hardship. What is being asked is similar to the extremely rarely granted hardship exemption that exists at the LPC.

In this case, the there are five hardships the developer says it is burdened by. The first is that there are unique physical conditions, including irregularity, narrowness or shallowness of lot size or shape, etc. make it impossible to comply with existing zoning. Second, that those physical conditions mean that there is no possibility of a reasonable return under current conditions. Third, that if a variance is granted, it “will not alter the essential character of the neighborhood or district.” Fourth, that the hardships are not the applicant’s fault. Fifth, that the variance sought is the minimum required to achieve reasonable return on the property.

At a hearing on Tuesday, at least some of the BSA members seemed wary of the proposal, presented by attorney Calvin Wong of Akerman LLP, Meisha Hunter of Li • Saltzman Architects, and cost analysis expert Jack Freeman. BSA member Dara Ottley-Brown accused the applicant of lowballing their estimates.

Like at LPC hearings, BSA hearings allow public testimony. In support of the project was Ann-Isabel Friedman of the New York Landmarks Conservancy, who referred to the former church as a place of “great beauty” and said the planned insertions and additions are “modest.” She called the project a “sensitive adaptation.” Also speaking in support was Tyler Donaldson, a resident of 12 West 96th Street, who said it was an “appropriate treatment.” Former LPC Chair Sherida Paulsen, now with the architecture firm PKSB, said the changes are “minimal” and will ensure a “new life” for the landmark.

Opposition was led by attorney Michael Hiller, representing the Central Park West Neighbors Association. He called the hardship application “considerable hubris.” He said they are grossly underestimating the value of the property, said a private school or a museum would be a better use of the structure. He also said the windows would be too close to neighboring 370 Central Park West.

Kate Wood of Landmark West! said she was “genuinely sad” and called the application “frivolous and inadequate.” “Do we continue this game?” she pleaded to the BSA members. She noted that the Children’s Museum of Manhattan once considered the site.

“We do not sacrifice our historic monuments,” said activist Susan Simon, adding that the proposal was “ill-conceived.” Architect and neighbor Luis Salazar said the church is not “functionally obsolete” and that the conversion would “permanently alter” the character of the community.

Several others testified against the project, including a resident of 370 CPW, who said she moved there for the “amazing peaceful serenity.” Another woman testified that seeing people moving around inside the building would be very different from seeing translucent stained glass windows. Speaking of windows, another person testified that she saw some windows have been left open to the elements as repair work is already underway.

Where does this leave the project? The applicant will compile a revised submission, which the BSA said must “dazzle” them. Then opposition will submit a rebuttal. All of this is expected to come to a head with a decision on January 12, 2016.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

Dear Mr. Bindelglass, it’s great that you are making this matter better known. One thing you might have made clearer is the contention of Michael Hiller (lawyer for CPW Neighbors Asso., whom you quote above) that the “hardship” claimed by the developer is a consequence of zoning regulations, not of the physical nature of the building or of the site as a piece of land. The law explicitly says that effects of zoning restrictions cannot constitute grounds for “hardship.” The fact that many windows in the church building are c. three feet from the property line, for example, is not a problem with the building as a building. It becomes a problem when someone wants to convert the church to a multiple dwelling, because multiple dwelling law says that LR and BR windows are to be 30 feet from the property line in this sort of corner building. Because this sort of difficulty is a consequence of zoning restrictions, it doesn’t qualify as a hardship that justifies the variances that have been requested.

If the effects of zoning restrictions are allowed to justify hardship claims and get developers variances — we lose our zoning! It becomes null.