YIMBY readers may be getting used to announcements of Long Island City superlatives, such as the tallest hotel in Queens nearing completion close to the borough’s tallest residence, which was recently surpassed by the city’s tallest apartment building outside of Manhattan. Even against these headlines, the complex rising at 28-10 Jackson Avenue, designed by Goldstein, Hill & West, takes scale to a new level. With over 1,900 units, 28-10 Jackson Avenue nearly doubles the offerings of the massive, 974-unit Hayden under development a few blocks west.

Its roughly 83,000-square-foot lot takes up two city blocks and erases West Street off the map of Queens. The tower at 28-02 Jackson Avenue, which is approaching its final, 45-story height, already dominates the local skyline, and will soon be joined by its 53- and 43-story siblings at 28-30 Jackson Avenue and 30-02 Queens Boulevard, respectively. Together, the triple slabs, ranging from about 500 to 600 feet in height, would rank among the borough’s tallest. The project is jointly developed by Tishman Speyer and H&R Real Estate Investment Trust. The ground level would house retail space.

Note: the latest redesign increased the height of the east tower from 33 to 42 floors, nearly matching the 45-story tower across the yard.

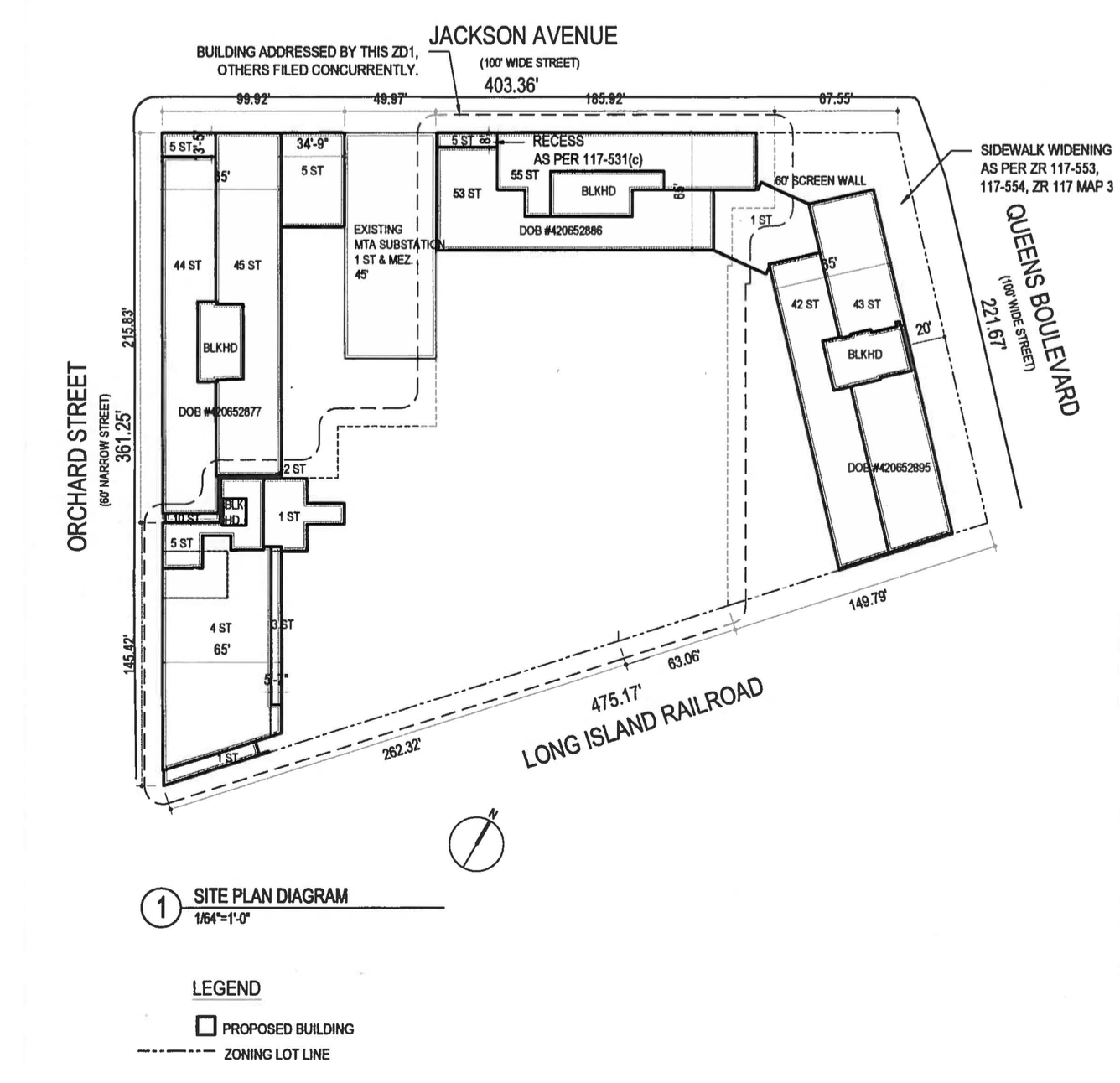

Master site plan. Image via the DOB

The complex sits at arguably the most important intersection in all of Queens. Jackson Avenue, the principal arterial of Long Island City, runs to the north. It intersects with Queens Boulevard, the most important thoroughfare in all of western Queens. At this point, Jackson Avenue becomes Northern Boulevard, which rivals Queens Boulevard in importance as it continues north and east, uninterrupted, to central Long Island (and much farther east if you include its extensions under different names).

In turn, Queens Boulevard becomes Queens Plaza, a short but important conduit that funnels the three thoroughfares to Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge, which starts just 1,000 feet northwest. In addition, every subway line that connects Manhattan directly to Queens runs either above or below this intersection, except for the nearby F train. The N, Q, and 7 trains rumble above, on their way to the adjacent Queensboro Plaza station, while the E, M, and R join beneath the surface at Queens Plaza station.

According to commonly accepted principles of urban design, locations with the best transit access ought to support the highest densities. It is fitting one of the largest apartment complexes in the borough sits at one of its most important transit junctions, which sits just one stop away from Midtown Manhattan.

Surprisingly, this pivotal location was severely underused for most of the nearly 100-year-long history since the junction was built. Since the turn of the 20th century, the site was home to the West Chemical Company, also known as C.N. West Disinfectant, housed within turn-of-the-century industrial lofts, low-slung warehouses, and surrounded by parking lots. A single, five-story residential tenement stood on Jackson Avenue at the center of the compound, dwarfed by the imposing brick rectangle of the MTA service structure sitting above the Queens Plaza station.

West Chemical used the site to manufacture products such as floor waxes and industrial cleaners until they moved out in 1977. Afterwards, the buildings served as Board of Elections offices, auxiliary space for the Modell’s Sporting Goods store chain, and artists’ space. Over the years, tenants deserted the space, which devolved into a district of dereliction, danger, and downright dread. During the late 20th century, Long Island City became notorious for its decay, and at this time, the old factory was largely inhabited by the homeless.

When Nathan Kensinger, a Curbed NY contributor and abandonment aficionado, explored the decaying precinct three years ago, he came upon a post-apocalyptic, surrealist landscape. It was hard to predict what the next building, floor, or room would offer. Some spaces were fashioned as makeshift bedrooms, book and DVD libraries, and even a theater. Others featured more unusual curiosities, such as traps assembled from plastic sheets strung from wall to wall. Half-finished paintings and sculptures shared space with heavy machinery lingering from the factory days. The floors were still strewn with debris that ranged from industry-related pamphlets dating back to the 1950s, to more ominous artifacts that indicated illicit and unsavory activity. One floor sported makeshift kennels and a padded ring, suggestive of dogfighting. The abandoned factory was a delirious encapsulation of the haunting, chaotic New York of the 1970s and 1980s, offering everything from its artistry, culture, and ingenuity, to its abuse, crime, and desperation.

Tishman Speyer, one of the city’s biggest real estate developers, has been planning to redevelop the two-block lot for at least a decade. Prior to demolition, the buildings briefly blossomed as a hot graffiti destination in the manner of 5Pointz. This impromptu art display was documented by Bad Guy Joe in December 2013. Over the following years, the decrepit structures were torn down, the environmental cleanup process completed, and first foundations were in place for the massive residential complex.

By this point, the seedy, decaying Long Island City of yesteryear was quickly slipping away into history books and photography blogs. After sweeping rezoning and upgrades to the local streetscape and public transit, aging commercial and industrial properties quickly made way for a brand new neighborhood of apartment towers, office space, and hotels. Around three dozen projects are currently under development in the neighborhood, particularly within the Court Square/Queens Plaza district, which is roughly delineated by the Sunnyside Yards to the south and the elevated curve of the 7 train to the north, east, and west.

Among the wide array of developers, three companies stand out as the main players. Rockrose is introducing thousands of residential units within three 40- to 55-story towers, which are lined up along Court Square. The two Heatherwood Properties buildings by Queens Plaza are more slender and vertical in their design, with Tower 28 now standing as the second-tallest building in Queens.

Tishman Speyer is building its own enclave at the junction of Court Square and Queens Plaza. Across the street from 28-10 Jackson, the developer is proposing the largest commercial complex in the neighborhood, and perhaps the borough. Two Gotham Center was completed several years ago, and two more towers are on the drawing boards at Jackson Avenue and Queens Plaza South. YIMBY hopes that Tishman builds a connector between the adjacent Queens Plaza and Queensboro Plaza subway stations within the basement level of the new office complex. This would not only serve the general public by improving local transit connectivity, but would also make the complex more lucrative for prospective tenants, and would likely grant the developer additional buildable space in return for the public amenity.

The complex, connected by a series of low-rise structures, consists primarily of three buildings. The east tower at 30-02 Queens Boulevard faces the elevated 7 train and currently stands around 20 stories tall. Permits list it as 442 feet and 42 stories tall, set to contain 550 units. This building got a significant height bump from its initially-proposed 33 floors.

The tower facing the north end of the site sits at 28-30 Jackson Avenue, and currently stands around 10 floors high. According to renderings and permits, it would become the largest of the group, and likely the third-tallest in the neighborhood upon completion. Its 590 feet (not including the bulkhead), 53 floors, and 658 units would make it one of the city’s largest buildings outside Manhattan, and put it on par with some of the larger tower slabs that form the Midtown skyscraper plateau.

The westernmost tower has made the most significant progress among the three, rising to 40 stories at an astonishing speed. The building is close to its eventual 45 floors, which would stand 470 feet tall plus the bulkhead, and contain 671 residential units. Though its permit address is 28-02 Jackson Avenue, most of the building faces the quiet and narrow cul-de-sac of Orchard Street.

Aside from site plans and basic massings, project details are scarce. We still do not know what would go into the courtyard. We suspect that it might be a green space. While the presence of a verdant backyard is still uncertain, the project faces Dutch Kills Green across the busy intersection, the only significant green space in the immediate vicinity. The former parking lot-turned-park would be visible from many of the project’s north-facing windows.

The master plan consists of three skyscraper slabs rising around a common yard. On the surface, the project has all the trappings of modernism, from its use of sheer, glass curtain walls, to its unyielding rectilinear geometry, and elimination of a cross street in order to create a superblock.

However, the project’s layout follows a traditional urban paradigm. Each of the three buildings rises directly from the sidewalk. Together with the low-rise structures in between, they establish well-defined street walls along the public perimeter. The MTA structure, which once dominated the block, is now dwarfed by the new complex rising all around, yet its brick façade is seamlessly integrated within the composition. The streetwall-and-courtyard block is closer in concept to the dense blocks of Barcelona than to infamous towers-in-a-park that is often associated with modernist superblocks. The only significant setback occurs at the east edge of the site, where the project shifts away from the adjacent elevated train to create a much-needed widened sidewalk. A small plaza also appears to face Queens Plaza at the northeast corner of the site.

To the south, the project faces the sprawling Sunnyside Railyard. We have yet to see how the development would meet this condition, but we hope the architects will make it compatible with a possible future deck over the railyards. Certain anti-development citizens predict doom and gloom at any prospect of decking over the yard, assuming that tall building would fill all of the yard’s 192 acres. Such fears are unfounded.

It is extremely unlikely that the eastern portion of the yard, which faces the low-rise neighborhoods of Woodside and Sunnyside, would be decked over any time in the coming decades. The expense is simply not worth it when there is so much other land available nearby for development. However, if the project were to be done in phases, the first, and likely the densest, phase would probably sit immediately south of the 28-10 Jackson Avenue complex, between the elevated bridges of Thomson Avenue and Queens Boulevard.

Any development built here would go a long way towards connecting Court Square and Queens Plaza to the neighborhood to the east. Though even this move appears cost-prohibitive at the moment, it is likely to become a lucrative venture once the adjacent neighborhood is built out, which is likely to happen sooner rather than later.

Upon completion, the apartments within the complex would boast some of the best views anywhere in the borough. The railyard to the east and south, in conjunction with the open space of Queens Plaza and the relatively-low skyline of Queens Plaza North, allows for sweeping vistas stretching for miles.

The three buildings would be tall enough to tower over most of the taller neighbors standing to the west and north. Even the similarly-scaled QE7 apartment building under construction on the other side of Queens Boulevard faces its narrow side towards the complex at 28-10 Jackson, minimizing its impact. If anything, the biggest view obstruction comes from the buildings themselves as they stand in one another’s way.

Even in its unfinished state, the west tower already exerts a commanding presence upon the neighborhood. When complete, the complex will dominate the brand new Long Island City skyline. While the thousands of new residents and new retail would infuse energy into the emerging neighborhood, the triple towers clad in sky-blue glass will proudly announce that Queens has finally arrived as a serious contender on the city skyline.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

The article contains a good suggestion — to connect the various elevated train lines at Queensboro Plaza, with the various underground subway lines which run below, at Queens Plaza. This would be a benefit for all of Queens County commuters, not just LIC.

Heatherwood: where you can pay a lot of money for broken elevators, heat, gas leaks, construction noise and hazards, and suuuuupeer rude Long Island management.

Construction is everywhere in Long Island City, work hard work in progress for residential. (group of towers)

I disagree

– Krystal