New York City’s various media publications have been reporting on the worsening transit crisis with increasing frequency, and as the headlines make clear, the state of the subway is bleak. But combining what’s already-happening with what’s impending begs the question no one seems to be asking. In a city where subterranean infrastructure is already decaying quite rapidly, when will rising tides of increasing frequency result in a transition away from underground transit?

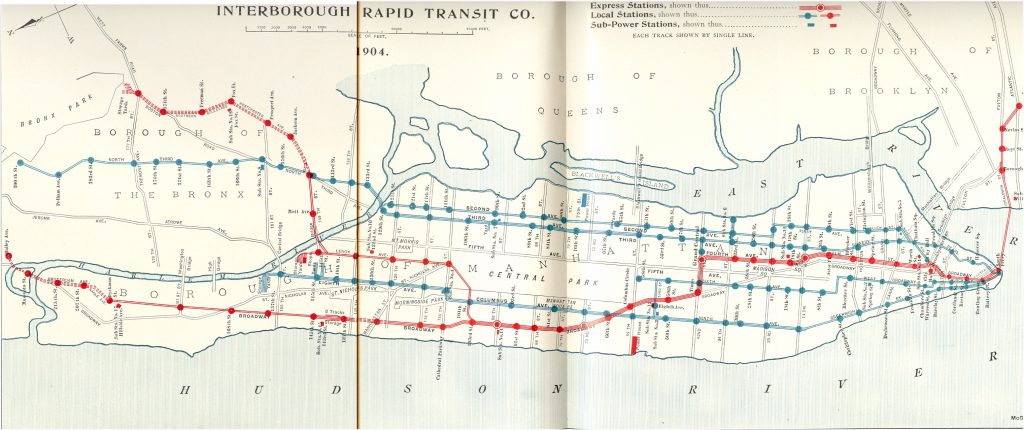

Subways have served the five boroughs fantastically since they first began sprawling underneath the city in 1904, but Sandy alone caused $5 billion worth of repairs to the system. Those repairs have only been partially completed, and despite token efforts, resiliency is essentially an afterthought, with “preventative” efforts consisting of token improvements to grates and inflatable barriers.

With only one example costing the MTA $5 billion, New York City’s subway system has already been brought to the brink of functionality. Five years after the storm, the L Train is still set for an imminent fifteen-month shutdown to cope with what happened.

Sandy alone seems unlikely to cause a shift from current bureaucratic thinking on where to spend infrastructure dollars, but the impending inevitable foretold by David Wallace-Wells, among others, means similar events in the near future are likely to inundate the city’s underground infrastructure with little regard for “once in a century” intervals as was typical in previous centuries.

The inevitability of a Sandy-or-worse repeat further shows how ill-spent repair money has been. In fact, the new South Ferry subway station is even further below ground than the old, which is partially why the cost was so exorbitant ($500 million+). The MTA continues to apply tried-and-failed methods of dealing with a crisis that continues to worsen, and this may ultimately cost New Yorkers a functional public transit system for the near future.

The solution to the crisis is obvious and has already been used to deal with the city’s expanding transit needs in the past. Elevated trains across Manhattan’s Avenues and crosstown thoroughfares would alleviate the congestion below ground substantially while adding enormous capacity to a system that is filled with chokepoints.

More importantly, an effective network of elevated trains would allow for closure and repair of portions of the subterranean network on a more frequent basis without massive repercussions across the entirety of Manhattan.

Prior to the dominance of the current underground network, Manhattan had elevated lines on Second, Third, Sixth, and Ninth Avenues. The island’s peak population of 2.33 million back in 1910 likely belied a total population that is still somewhat smaller than today’s weekday normal of four million, but it is undeniable that 100 years ago, Manhattan was home to several hundred thousand additional residents.

At the time, “El” trains were seen as horribly noisy and slow methods of transport. While they certainly had negative externalities, they allowed a system with a larger capacity, and also encouraged multiple stories of street-front retail that persist today along former routes like Sixth Avenue.

Subways, at the time, were preferred as “new” and efficient alternatives to a hulking system that ended up being completely dismantled. This is now the attitude that must be taken with regards to the current subway system, which is too big to fail, and so must be rapidly augmented by new elevated lines that alleviate the pressure when it inevitably does.

Perhaps the largest argument in favor of elevated transit is cost. Subway extensions in New York City are the most expensive infrastructure projects on the planet, running into the billions per mile. Elevated trains cost roughly one tenth as much, even in a place like New York, offering immensely more bang per buck.

More importantly, additional subway lines are far larger liabilities than new elevated transit, with the situation in 2012 making this beyond obvious. Beyond their gargantuan construction costs, the shelf-life of these infrastructure “improvements” is far shorter than anything that warrants their initial existence if they must be shut down and restored at an interval greater than every few decades.

New York City’s continued growth is dependent on reliably increasing the city’s transit capacity. And with the subways unable to keep up with demand, technological improvements to elevated transit that have resulted in quieter and cleaner trains make the restoration of the El network an attractive alternative to sinking the MTA’s investments further underwater in a system that is also heading in that direction.

While the negative externalities of elevated transit are impossible to mitigate entirely, the benefits still outweigh the costs, especially when it comes to affordability of surrounding real estate. Areas proximate to elevated transit are likely to see decreases in pricing per square foot, while concurrent upzoning could still make redevelopment very feasible (in the end, neighborhood housing prices would likely see substantial drops).

The potential decreases in pricing per square foot next to new elevated lines could be a point of contention in the long line of legal dramas that have marked the evolution of transit in New York City. In fact, construction on elevated lines ground to a halt in the late 1800s as opponents managed to find increasing room to litigate against the rail companies, partially resting on the legal basis that the negative externalities and resulting price hits to neighbors constituted a taking.

While this was a concern in Story v. New York Elevated R.R. Co., that case was ultimately decided in 1882, before the existence of air rights. New trains would certainly be cleaner, quieter, faster, and more attractive than the clanking and polluting metal monsters of yesteryear, but most importantly, the city also now has tools like zoning and air rights. Any losses to present property value can be more than compensated through corresponding increases in allowed air rights.

Repealing the state’s limit on residential FAR (set at 10, or 12, with inclusionary housing) would best enable Manhattan to take advantage of these improvements, but even within existing bounds, many neighborhoods could see substantial densification.

The city’s fascination with operating obsolete historic infrastructure also unfortunately extends to its built fabric, with many neighborhoods of purported landmarks now existing in areas where initial builders had no intention of eternal permanence. The same considerations for the future of the subway must be made for areas like the East and West Village, which will imminently require massive taxpayer-funded seawalls to maintain their quaint and exorbitantly expensive charm.

While these neighborhoods certainly have landmark structures, their current use is incompatible with a future that will demand billions of public dollars for the preservation of Manhattan real estate and the creation of new infrastructure. Encouraging developers to incorporate the facades of the old structures would be one way to keep their legacy alive, but change one way or the other is inevitable, and the Great Wall of Red Tape associated with landmarking is a woefully inadequate defense against storm surge.

Combining the opportunities afforded by impending changes shows that the future need not be bleak. But while exorbitant underground construction projects may have been signs of progress in the New York City of yesteryear, $4 billion “Transit Hubs” are now leaking on sunny days, so what happens when Sandy’s next iteration pays a visit?

Abandoning the subways outright is not an option, but offering options for legitimate resiliency most definitely is, and the most cost-effective and time-efficient way of accomplishing this is by rebuilding elevated transit. Besides removing pressure from the subways and allowing things like nighttime repairs to become a reality, this would also allow a development boom, lowering rents both through sheer bulk of new supply and perceived (i.e. mostly imagined) negatives relating to elevated transit.

El trains will certainly have their critics, but actions speak louder than words, especially when they involve closing entire subway lines for fifteen months. New York City needs a solution that spans the five boroughs to solve its worsening transit crisis, and it is already staring the city in the face, it is only a question of whether there is any political motivation to take action.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

THE EL YOU SAY!

yes, let’s go back to the future.

HA HA HA HA ……

I told everyone not to rebuild the World Trade Center at its former location because of rising sea level. Nobody listened, nobody cared. Sandy proved I was right!

Same for (Xanadu) Meadowlands Sports Complex, Newark Airport, J.F.K airport, ..

Just look at the map: http://ss6m.climatecentral.org/#12/40.7194/-73.9670

Hello..YIMBY..no and not New York’s transit like this, bad happens came through but we will there to serious with heavy flood, move damage go out and make its service come back again. In this location that people and trains to uses with its normal platform not water covered on the elevators, and I can’t hold hard concept of subway to cheer me deep down. (Sandy is passed but problem is pause)

Sea level is only going to rise a little bit in the next century. I’m sure we can build a foot of wall along the coast by then. All this climate change hype is exaggerated

Very few experts agree with you. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/massive-seawall-may-be-needed-to-keep-new-york-city-dry/

I believe a much expanded system of free-to-the-user water transit is a big part of the answer. The water taxis would have to be fast, and run much more frequently than any do today. Consider 5 minutes the top wait time for any rider at any location along the Hudson or East Rivers. Fast and no cost (to the user).

Pair this with seamless transfers to existing above and below grand transit.

To move people quickly to the river shorelines from the center of the island, pair this expanded water-taxi system with new, fast ground transportation across the island at major avenues.

I rode the old Myrtle Avenue El way back when. It was akin to the structure of the 3rd Avenue El above. Wooden cars that rattled and a structure that swayed when we hit so me speed going passed Ft. Greene Park. They wish they had it back for service the Navy Yard today.

Has the implementation of trams been studied? Trams are cheaper and have a much smaller visual impact than elevated railways.

Paris and London have started using trams as well, in addition to metro/ subway.

Second the idea of trams! Toronto is another example of successful use.

I second the return of ELs, Sal Palo is doing great things with modern, 7 car, automatic monorail with climate controlled stations no less. Wide quiet cars with open gangways run on rubber tires. Seattle’s monorail is sleek and unobtrusive and at 50years old you barely hear it pass by overhead except for the whine of the motors. The slim structures could light the streets and night with LED lighting and be built higher so that in the day they allow far more light to the street than a wide and heavy 1900’s EL could have ever done. Precast concrete is easy to replace and repair than steel. Snow would have little place to accumulate on a 30″ wide beams. Take some time and search gmaps and youtube for examples of the two systems I mentioned. The city could install a loop on two Avenues, 3rd on the east and 9th on the west crossing over near south ferry and 116th. Could probably build the whole thing for the price of the 2nd Ave Stubway extension. I believe such investment would add resiliency as suggested but would raise property value rather than diminish it.

I couldn’t see Sal Palo with rubber tires… How far would you run on the 3rd and 9th? From what street to what street?

Yeah this article is obviously very biased towards one opinion. I believe that climate change and environmental destruction is an issue however, I disagree with the pessimistic crowd. It’s illogical to think that humans cannot to adapt to improve for the future. Elevated transit is fools gold in a city as densely populated as NYC. Could you imagine the hysteria that would be created by an elevated line being constructed down 2nd avenue. I do not believe that elevated tracks are the solution. I believe that finding ways to protect the tunnels is mor crucial during the time of the storm. For example using fiber glass cords instead of copper would’ve saved millions in construction costs after sandy. The biggest problem with NYC subway right now is that it is underfunded. Upstate NY has robbed the city of necessary investments that need to be applied to the system ove the past few decades. Maybe the solution is more control of the subway by the city instead of the state. Why are guys who live in Albany deciding the daily commute of people taking the A train to work on Monday morning?

Your ideas are not in opposition with the authors. The policy and funding side needs reform too. I think the Authors point is that the current system running at peak efficiency is still not large enough to deal with demand. And that the capital costs to build more capacity is unnecessarily large for underground subways.

Leave it the way it is. It’s history. It works. Picture it not working at all on 5 degree day, or a 105 degree day. No more heavy people. Ny’ers are some of the biggest cry babies on earth these days. While some you pay $10 or more for a good cup of coffee.

So clearly most of the people commenting here have absolutely no idea what their talking bout and make no sense so let me bring some light on this issue.

I live in the Bronx and I live near the elevated 2/5 lines, their loud. heir old. Their rusty. Their a burden to the surrounding commercial and residential environment. They leave the road below it extremely under maintenance and have the sidewalk blending in with the asphalt to the point where parking is so close to the buildings beside it. Elevated trains continue to pollute and cause an increase in waste product because of how people are more likely to throw their trash in the tracks that have holes and crevasses to the street below. Not to mention when it rains or snows and you have water pouring all over your clothes if you stand in the wrong place. I could go on and on about how bad elevated trains are, the views aren’t even that good either when all you’re looking at is a bunch of run down, low density, housing with empty trash lots and graffiti covered building sides.

Building elevated lines in Manhattan would cause havoc and 100% utter disgust by all Manhattan residences that would live and work near those monstrosities. Yes they are cost-effective but they cause so many more problems that people would have to deal with whenever their not a train. Yeah I can go downtown by walking a few blocks now but what about all the obstructed views, rusted pillars, falling trash, space take up and so much more.

Subways are only that expensive because of how corrupt the MTA is and how the City and State don’t get along when it comes to almost anything so the tax payer and rider is put under a lot of pressure that shouldn’t be there. Lets really talk about the issue here

Trams cause delays for pedestrains and road vehicles, either raised, or subway. It is true that much of the subway system is delapatated and needs repair, infact, there are tunnels and stations that are abandoned. The old system of tunneling was inefficent and costly, compared to todays standards, and the construction materials used today are far better and last far longer than that used when much of the subway was built. So, rebuilding the subway might initaly cost some money, but will last generations!. The alternative, build raised tracks that are unsightly and noisy, I doubt the people in the affected streets will go for it, so it probably won’t happen!