On January 28, the Department of City Planning released the Environmental Assessment Statement (EAS) for the proposed Residential Tower Mechanical Voids Amendment, which seeks to limit non-residential floor heights in future apartment towers within high-density districts. The 48-page document, which outlines the proposal and its impact, reveals a troubling foundation of groundless speculation, elusive language, and self-contradictory statements. The proposed amendment ultimately promises to stifle flexible planning, and fails to present a convincing argument in its support.

The following analysis focuses on the proposal’s most problematic aspects. Quotation brackets indicate our concise edits of redundant phrasing.

The opening Project Description reads as follows, in full:

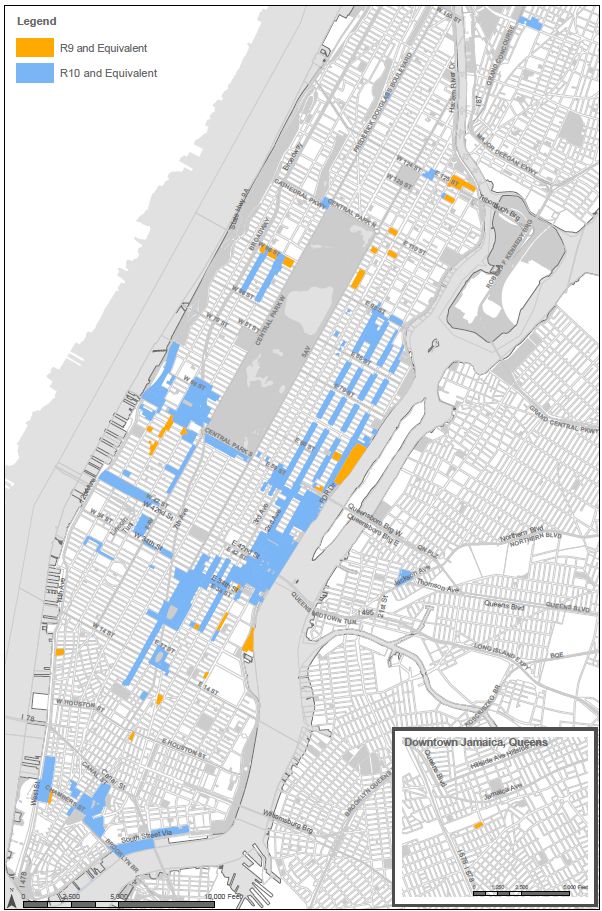

- The New York City Department of City Planning (DCP) proposes a zoning text amendment pursuant to Zoning Resolution (ZR) Section 23-16 (Special Floor Area and Lot Coverage Provisions for Certain Areas) and related sections, to modify floor area regulations for residential tower developments located within non-contextual R9 and R10 Residence Districts, their equivalent Commercial Districts, as well as Special Purpose Districts that rely on underlying floor area and height and setback regulations or that are primarily residential in character. The proposed zoning text amendment (the “Proposed Action”) would count mechanical floors in such buildings as zoning floor area when they are taller than 25 feet in height or when they are located within 75 feet in height of each other. Currently, mechanical space does not count towards zoning floor area of a building as permitted by zoning. The Proposed Action is intended to discourage the use of excessive mechanical floors to artificially increase building height by limiting the height and frequency of such spaces incorporated into a building’s design.

The last sentence marks the first of twenty-five instances of the word “excessive,” or its derivatives, used throughout the document. Surprisingly, the proposal fails to conclusively explain what makes certain mechanical spaces “excessive,” or why they must be restricted. Every attempt at an explanation ends up contradicting self-evident facts, its own criteria, or both.

“Protection” of Skyscraper Districts from Skyscrapers

Zoning codes restrict building heights throughout the city, except where exceptionally favorable conditions, such as wide avenues and abundant mass transit, allow planners to dispense with height limits. Even in these areas, floor-area ratio limitations ultimately govern building height and bulk. The proposed amendment seeks to effectively impose extra height caps in these exceptional districts, namely R9 and R10. In effect, the proposal seeks to “protect” specially-suited skyscraper districts from skyscrapers.

Equally confusing is the Urban Design and Visual Resources statement (page 11) claiming that “the Proposed Action would not alter the permitted height, bulk, setback or arrangement of the existing zoning districts,” even as the project description explicitly calls for restricting building height through revised FAR calculations.

Dubious Formulas Conflate Separate Zoning Concepts

The amendment interchangeably uses distinct concepts within the city’s zoning code. Section II: Background of Appendix A opens with a reminder that current city zoning excludes mechanical floors from zoning area calculations, and does not limit the height of such spaces.

Floor-area ratios regulate usable floor area, which represents the number and type of building occupants (e.g. residents or office workers), factors that impact city infrastructure (e.g. roads, mass transit, schools, utilities). Logically, FAR does not extend to mechanical space, which services the building itself and thus does not affect urban infrastructure nor functional urban density.

By contrast, height limits concern only the building’s vertical extent, in conjunction with setback planes that shape the structural form.

In other words, floor-area ratios, height limits, and setback planes operate as interdependent qualifiers, governed by related but separate formulas.

The following is an excerpt from Section III, Proposed Action:

- [Mechanical floors] taller than 25 feet (whether individually or in combination) would be counted as floor area. Taller floors, or stacked floors taller than 25 feet, would be counted as floor area based on the new 25-foot height threshold. A contiguous mechanical floor that is 132 feet in height, for example, would now count as five floors of floor area (e.g., 132/25 = 5.28, rounded to 5)

The proposed calculations would convert height into FAR and equate unusable space with usable, conflating deliberately independent definitions.

- The 25-foot height is based on mechanical floors found in recently-constructed residential towers and is meant to allow the mechanical needs of residential buildings to continue to be met without increasing the height of residential buildings to a significant degree. The provision would only apply to floors located below residential floor area to not impact mechanical penthouses found at the top of buildings where large amounts of mechanical space is typically located.

- Additionally, any [mechanical floors] located within 75 feet of one another that add up to more than 25 feet in height would count as floor area. This [addresses] situations where non-mechanical floors are interspersed among mechanical floors in response to the proposed 25-foot height threshold, while still allowing buildings to provide mechanical space necessary in different portions of a building. For example, a cluster of four fully mechanical floors in the lower section of the tower which total 80 feet in height, even with non-mechanical floors splitting the mechanical floors into separate segments, would count as three floors of floor area, even when each floor is less than 25 feet tall and they are not contiguous (e.g. 80’ / 25’ = 3.2 rounded to the closest whole number equals 3).

The proposal arrives at the 25-foot threshold through precedent observation, rather than expert engineering review. Reasoning behind the 75-foot figure is altogether absent. Still, empirical justification, even imperfect as it is, is laudable.

However, the proposal throws out its logical premise when it applies this mechanical argument to explicitly non-mechanical spaces:

- The regulations would also be made applicable to floors occupied predominantly by spaces that are unused or inaccessible within a building. The Zoning Resolution already considers these types of spaces as floor area, but it does not provide explicit limits to the height that can be considered part of a single story within these spaces. This change would ensure that mechanical spaces and these types of spaces are treated similarly.

The text provides no further explanation for this arbitrary decision. Since the amendment repeatedly stresses the “need to discourage excessively tall floors,” the clause reads as a forced motion to restrict design flexibility by any means, whether justified or not.

Lack of Relevant Precedent

The precedent study, purportedly cited in support of the proposal, inadvertently proves why the amendment is unnecessary in the first place. Its numbers show that mechanical void heights remain overwhelmingly consistent in zones both with and without existing height limits.

Quoted from Attachment A, Section II, Background:

- The Department conducted a citywide analysis of recent construction to better understand the mechanical needs of residential buildings and to assess when excessive mechanical spaces were being used to inflate their overall height. DCP assessed the residential buildings constructed in R6 through R10 districts and their Commercial District equivalents over the past 10 years and generally found excessive mechanical voids to be limited to a narrow set of circumstances in the city. In R6 through R8 non-contextual zoning districts and their equivalent Commercial Districts, the Department assessed over 700 buildings and found no examples of excessive mechanical spaces.

There is not a single instance of “excessive” mechanical voids out of 700+ buildings in districts R6 through R8.

- DCP attributes this primarily to the existing regulations that generally limit the overall height of buildings and impose additional restrictions as buildings become taller through the use of sky exposure planes.

The DCP speculates that, in these districts, height and bulk limits restrict heights of mechanical spaces. However, if height caps were the only factor, the inverse would have been true, as well: developers would pursue every opportunity for tall mechanical spaces where height limits are absent.

Instead, the analysis refutes its own reasoning in the very same paragraph.

- R9 and R10 [zoning districts and their equivalent] do not impose a limit on height for portions of buildings that meet certain lot coverage requirements.

- In these tower districts, the Department assessed over 80 new residential buildings and found that most towers exhibit consistent configurations of mechanical floors. This typically included one mechanical floor in the lower section of the building, and additional mechanical floors midway through the building, or regularly located every 10 to 20 stories [in taller towers]. In both instances, these mechanical floors range in height from 10 to approximately 25 feet.

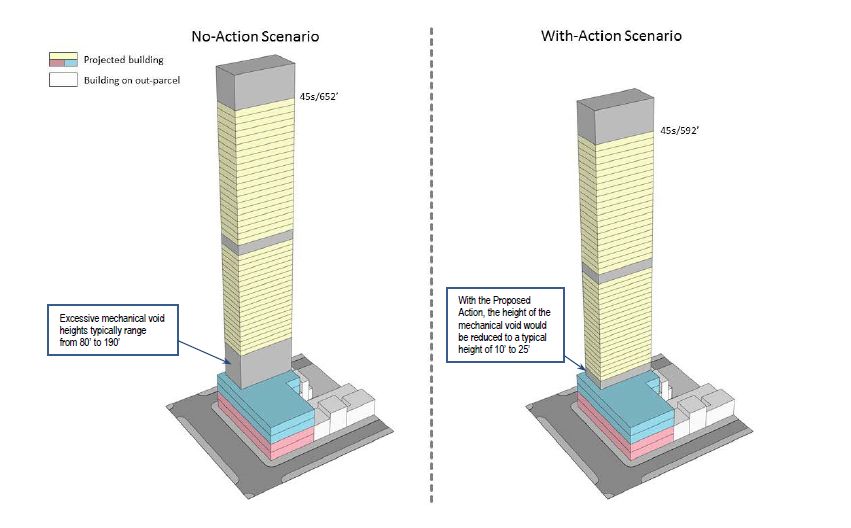

- The Department identified seven buildings, either completed or currently undergoing construction, that were characterized by either a single, extremely tall mechanical space, or multiple mechanical floors stacked closely together. The height of these mechanical spaces varied significantly but ranged between approximately 80 feet to 190 feet in the aggregate.

Evidently, mechanical space heights remain constant regardless of height limits. Only seven out of around 800 buildings, or 0.9% of the total, reflect conditions the proposal addresses. These findings confirm tall mechanical floors as rare responses to specific site and design conditions, rather than pervasive exploitation of the code, as the proposal implies (e.g. page 26).

Precedent Misrepresentation

With near-total absence of precedent to indicate a persistent issue, the proposal seeks instead to formulate a problem based on a singular example. The document openly reveals its grounding in a specific Mayoral directive, which apparently stems from his dislike for the aesthetics of a particular building, namely 249 East 62nd Street:

- Renderings of a proposed residential tower on the Upper East Side released in 2018 showed four mechanical floors taking up a total of approximately 150 feet in the middle of the building and raising its overall height to over 500 feet, far above other buildings in the surrounding area built under the same regulations. In response to this building, Mayor De Blasio requested that DCP examine the issue of excessive mechanical voids that are used in ways not anticipated or intended by zoning.

A skyline-bound glance readily refutes this blatant exaggeration. 249 East 62nd Street would rise only about 2,200 feet northeast of 432 Park Avenue, which towers nearly thrice as tall. 806-foot-tall Bloomberg Tower stands much closer, less than 1,300 feet away. Several buildings of comparable height to the proposal, such as Evans View, The Rio, and The Savoy, stand within a 1,000-foot radius. 50-story Bristol Plaza looms just 600 feet to the north. 1059 Third Avenue, which shares the block with the proposed tower, rises nearly as tall.

As such, any claim that 249 East 62nd Street would rise “far above other buildings in the surrounding area” is verifiably false, even by the most modest definitions of what constitutes a surrounding area.

249 East 62nd Street, image by Rafael Vinoly Architects

Benefit-Disproving Case Study Prototypes

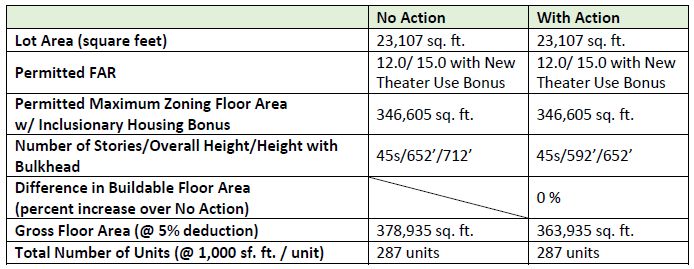

The proposal illustrates the amendment with three “generic prototypical developments,” where “no-action” and “with-action” scenarios differ only in their treatment of mechanical spaces.

Factors such as FAR, zoning floor area, number of stories, and number of units, remain constant. As such, the studies show that the amendment would not enhance any meaningful aspect of urban planning.

Case study chart shows that the amendment would not benefit any relevant building parameters. Credit: NYC DCP

Misrepresentation of Impact Upon Design Quality and Neighborhood Character

The Proposed Action section seeks to curb “excessively tall mechanical spaces that disengage substantial amounts of building spaces from their surroundings.” This vague statement may be read in two ways – that tall mechanical spaces hurt interaction at ground level, or that they harm urban composition through subpar design. The proposal argues in favor of both claims, yet fails to support either one.

The Ground Level Experience

The “neighborhood character” section purports that the amendment encourages buildings that “complement the surrounding neighborhood with active uses on lower floors.” However, the proposal’s text and imagery refute this argument.

The dark days of mid-century modernist planning, when sidewalk-facing blank walls were in vogue, are relegated to history books and to the suburbs, with remaining examples of such designs maligned by critics and ordinary citizens alike. The “New Urbanist” ideas of Jane Jacobs, which call for street-level transparency and pedestrian engagement, were considered radical in the 1960’s. Today, their universal acceptance is reflected in zoning codes, which dictate minimal street-level transparency and engagement in mixed-use districts.

Mechanical space, elevated even a few floors above ground, plays no role in the building’s direct street engagement. The case study prototypes show large, site-spanning bases, which engage the street in equal degree in “no-action” and “with-action” scenarios alike.

Even still, the proposal insists that the amendment would benefit the streetscape, despite its own evidence to the irrelevance of this premise in the context of mechanical space. The first of two development types discussed in the “neighborhood character” section recycles the example of 249 East 62nd Street, out of sheer lack of precedent:

- In districts where the tower-on-a-base regulations are applicable, like the Upper East Side building described above, these spaces were often located right above the 150-foot mark, which suggests that they are intended to elevate as many units as possible while also complying with the ‘bulk packing’ rule of these regulations, which require 55 percent of the floor area to be located below 150 feet.”

The statement concedes that, even in “stilt buildings,” the bulk of the floor area sits close to the ground level, reflecting sound urban planning both in spirit and in letter of the zoning law.

- In other districts, these spaces were typically located lower in the building to raise more residential units higher in the air, which often also has the detrimental side effect of “deadening” the streetscape with inactive space close to the ground.

As evidenced earlier, mechanical space elevated even one floor above ground level is irrelevant to functional street interaction.

The Mid-level Experience

The proposal’s defenders may counter the latter statement by arguing that, regardless of direct street-level function, an expansive span of inactive space may overpower the street wall, creating a markedly negative visual effect.

Indeed, this aspect of urban design is worthy of consideration. However, the inherently subjective nature of design means that aesthetic success or failure wholly depends on architect skill and planner creativity, which the amendment seeks to limit.

Massive blank walls of New York Hilton Midtown loom oppressively above Sixth Avenue, despite a lively retail strip at ground level. By contrast, the nearly-windowless, side-street-facing walls of the nearby 30 Rockefeller Center stretch even higher and wider, yet their gently-textured limestone and jubilant Art Deco motifs exude a pleasant street presence.

The more recent examples, all of which the proposal deems as “excessive,” exhibit similar variety. 249 East 62nd Street, much-censured by the proposal, attracts attention through audacious, minimalist structural expression, the trademark of neo-Modernist architect Rafael Viñoly.

Notably, the proposal makes no mention of 220 Central Park South, where classically-minded virtuoso Robert A.M. Stern discretely conceals tall mechanical floors beneath an ornamented limestone facade. Perhaps the amendment intentionally omits this “inconvenient” project, which proves that mechanical voids may, after all, be designed in an aesthetically pleasant manner.

Ground level at 220 Central Park South on West 58th Street; several apparent floors conceal mechanical spaces. Credit: Robert A.M. Stern Architects

The amendment similarly ignores the Snøhetta-designed tower proposed at 50 West 66th Street, where a dramatic skygarden graces the tower mid-section. If the amendment prevails, yet another featureless window stack would greet residents of adjacent high-rises, instead of lush greenery, elevation drops, and water features.

As such, despite the amendment’s boasts of “providing overall flexibility to support design excellence” (p. 14), and “reinforcing and improving existing neighborhood character and urban design” (p. 28), the proposal openly threatens creative design.

Hindrance of Waterfront Design

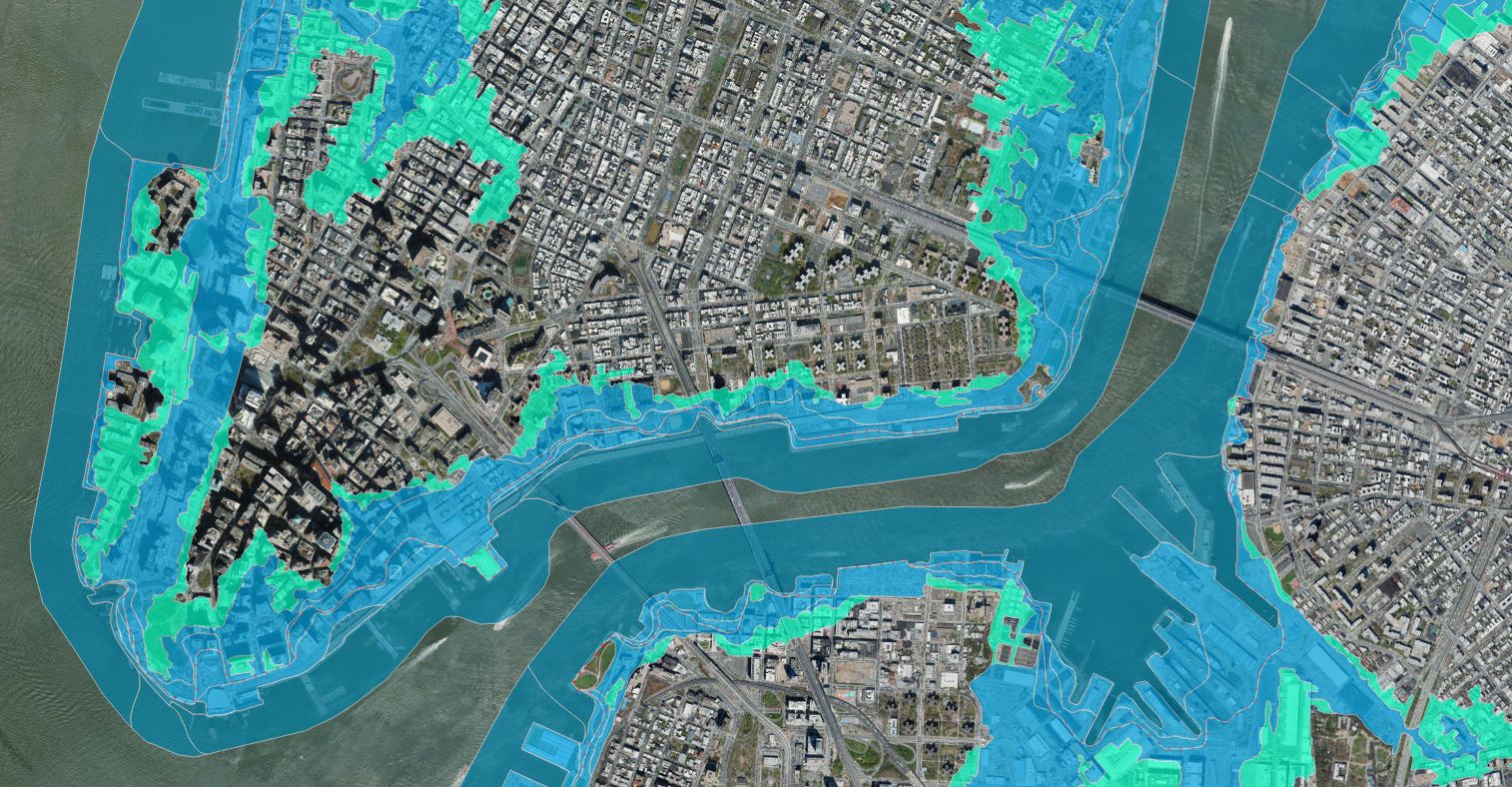

The proposal partially covers waterfront areas, so Attachment B includes an assessment for consistency with the Waterfront Revitalization Program (WRP). The program’s stated goal is to “maximize the benefits derived from economic development, environmental preservation, and public use of the waterfront while minimizing the conflicts among those objectives.” The review evaluates whether the proposal “promotes,” “hinders,” or “has no effect” on 45 policy points.

An appended checklist reveals “no effect” on most policies. Dubiously, the review claims to “promote” four policies, even though the proposal would arguably hinder all four instead.

- “Promoted” Policy 1.1: “Encourage commercial and residential redevelopment in appropriate Coastal Zone areas”

Bizarrely, not a single word of the supporting 200-word “argument,” which reiterates the proposal premise, explains how the amendment would encourage waterfront development. On the contrary, logic dictates that any development restrictions, including ones proposed by the amendment, would discourage both development flexibility and viability.

- “Promoted” Policy 1.5: “Integrate consideration of climate change and sea level rise into the planning and design of waterfront residential and commercial development, pursuant to WRP Policy 6.2”

- “Promoted” Policy 6.1: “Minimize losses from flooding and erosion by employing non-structural and structural management measures appropriate to the site, the use of the property to be protected, and the surrounding area”

Again, the explanatory paragraph, which addresses both policies, fails to describe how the proposal would promote either one. At best, its stated claim that “the Proposed Action will not inhibit buildings from being designed to address current or future flood risks” ought to garner both policies a “no effect” rating.

Disturbingly, the above statement appears factually incorrect, even as per the proposal’s own claims. Proposal Background (Attachment A) defends limiting above-ground mechanical space by stating that “larger mechanical spaces were generally reserved for the uppermost floors, or in the cellar below ground.” In the post-Sandy era, waterfront projects universally elevate equipment above ground level. Proposed restrictions on above-ground mechanicals would hinder flood-resistant design by forcing architects to reconsider using vulnerable basement space for mechanical equipment.

- “Promoted” Policy 9.1: “Protect and improve visual quality associated with New York City’s urban context and the historic and working waterfront”

The explanation alludes to “reduction of some building heights” without elaborating on how such action would improve the waterfront’s visual quality. Again, this policy deserves a “no impact” rating, at best. As discussed earlier, aesthetic preferences are inherently too subjective for empirical arguments, including impact on waterfront design. It is just as easy to argue that design limitations hinder, rather than promote, potential visual quality.

Flood zone map showing the Lower Manhattan waterfront, where, in certain areas, the amendment would discourage elevated mechanical space. Credit: NYC DCP

Self-Contradiction in Air Quality Impact Assessment

The proposal fails to accurately address not only the amendment’s functional, aesthetic, and development policy aspects, but even its mechanical characteristics. Its argument that the amendment “would not result in any significant adverse air quality impacts related to mobile or stationary sources” is contradicted by air quality guidelines established by the assessment itself.

The air quality review investigates potential impact upon adjacent buildings. For instance, rooftop mechanical exhaust may pollute the air next to a taller tower nearby. Since the inverse is also true, the report correctly states that “buildings of lower heights are not deemed to be under impact from a taller building.” Logic dictates that any reduction of building height would also lower their rooftop exhaust altitude, exposing a greater portion of adjacent skyscrapers to polluted air, which is a significant consideration in high-density districts covered by the proposal.

Instead, the report altogether dismisses the possibility of future extra-tall buildings, even in unlimited-height districts, alleging that “buildings of similar heights or taller than the [abovementioned] prototypes are not anticipated to be in the vicinity closer than the threshold distances derived from the screening analyses … no further detailed analyses are warranted.”

Conclusion

The New York skyline draws its globally-celebrated appeal from its incredible design diversity, which reflects its dazzling bouquet of people, culture, history, innovation, and architectural legacy. As evidenced above, the Mechanical Voids Amendment Proposal is the latest attempt to stifle design flexibility, under the guise of claiming the exact opposite.

Fortunately, the proposal exposes its own inadequacy through its poorly-composed premise, which stumbles through self-contradictions and logical gaps and readily disproves its own claims of supposed benefits.

The amendment infers that tall buildings are inappropriate for districts specifically zoned for tall buildings.

The text states that the amendment would both not affect building height and that it would restrict building height, at times within consecutive arguments.

Contrived formulas mix and interchange intrinsically separate zoning definitions.

A precedent study that attempts to prove broad zoning code misuse instead concludes that the purported “problem” is virtually non-existent.

The text claims a plethora of amendment benefits, yet the case studies readily show that the amendment would generate no functional positive impact.

The proposal omits mention of discretely-integrated and pleasantly-articulated examples of tall mechanical spaces, claiming instead that such design is universally detrimental.

General reasoning regarding mechanical aspects falls apart under scrutiny. In fact, the greatest void evident in the proposed amendment is the gaping absence of logic itself.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

pardon me for using your space

^Lock him up

Wrong

You might need a pardon, alright.

It’s just the deBlasio’s administration attempt yet again to appease the NIMBYs. In fact, almost all the city’s revised zoning codes since the Bloomberg administration and now deBlasio are all molded by inout from NIMBYs cry against height and density.

I understand why people might not want skyscrapers in neighborhoods like Park Slope, but now allowing tall buildings blocks away from Columbus Circle is asinine. While walking down the street there is hardly a difference in experience between a 30 story and 60 story tower anyway.

* input

I once worked for a department that had to move into an entirely renovated building, and the discussion of ow much space to use for the mechanical room came up. It was office space, and we new tenants did not want to see any more space than operationally necessary for mechanical equipment used. We had some arguments with the project manager, who discovered that the planned mechanicals required more space than originally allocated. We won out in the end by getting smaller, more efficient HVAC systems.

Apparently, those days are gone now, and it’s more profitable to lift high paying tenants skyward than to minimize construction costs.

More’s the pity, since people need places to live and work more than they need voids.

We are the hollow men

We are the stuffed men

Leaning together

Headpiece filled with straw. Alas!

Our dried voices, when

We whisper together

Are quiet and meaningless

As wind in dry grass

Or rats’ feet over broken glass

In our dry cellar

Shape without form, shade without colour,

Paralysed force, gesture without motion;

Sightless, unless

The eyes reappear

As the perpetual star

Multifoliate rose

Of death’s twilight kingdom

The hope only

Of empty men.

Empty men whose hollow edifices will be their legacy..

Oh, you poor developers and titans with tiny, fragile egos who must be lifted high above the hoi polloi! How dare anyone try to curb your hubris!

Mechanical systems or otherwise underutilized spaces (like parking garages) located just above ground level have a very negative impact on the pedestrian environment. Noise, pollution, and fewer “eyes” on streets all make sidewalks less safe. The disdain these buildings (and likely their part-time residents) have for the city around them is palpable.

I agree with you about underutilized ground floors, but this totally unrelated to this proposed amendment (maybe you’re thinking about the awful developments on 4th Ave, Park Slope?) None of the proposed buildings this amendment targets propose ground level or low floor mechanicals. How can you say the Snohetta designed sky park/ mechanical floor causes noise and pollution at ground level?

Also I agree with you that parking requirements should be reduced or eliminated (in areas with great public transit like Manhattan) and should be located below ground or otherwise not at street level.

The issue you’re missing is this is an amendment aimed at restricting building height in areas zones for unlimited height. If it were being honest it would be a proposal to rezone those areas with new height restrictions.

Perhaps this site should be called newyorkyitpored

(New York Yes In The Pocket Of Real Estate Developers)

Empty vertical space that blights the cityscape for no reason save to boost the profits of the real estate one percent should not be allowed, no matter this website’s assertions that the benefits have not been proven.

All you have to do is look around you to see the sense this makes.

Can you ‘grandfather’ in larger voids?

Whoever authored this piece understands the difference between zoning that is based on comprehensive planning and zoning that is purely political. Well done.

I think the author is conflating concern about the size of mechanical spaces with overall height of buildings. Nothing that I see seems to indicate that overall height is an issue (for the city at least). It’s the size of the void itself and the blighting effect it can have. Sure, if it’s clad nicely you may not be able to notice it, but not everyone hires Snohetta…

I really disagree, I think this is aimed at restricting overall height. Otherwise why would this amendment also propose to limit occupied floor heights to 12 feet?

I believe rules should be specifically directed at the problem they intend to address, so if it was all about blighted concrete walls then require mechanical voids to have the same facade materials as occupied floors or be surrounded by vegetated rain garden terraces.

This is definitely aimed at limiting height. The residents in the Lincoln Center area have been especially vociferous against new skyscraper construction.

It should be a relatively simple calculation; if void spaces are being artificially inflated to increase building height (but not evident according to this article), provide a maximum FAR exclusion for voids.

I suspect however that these conflicting code proposals are rooted in political, not actual architectural design or engineering concerns. Generally speaking I think the DeBlasio administration has done a competent job dealing with affordable housing and abatement reform, but all the high rise projects going on must be hot button issue for his base.

Mechanical voids it is a scheme, using to make building Higher without construction of actual floors, started with “Doomsday bunker” Lobby cube of One WTC, actual floor count starts at floor 20, questions where are other 18 not constructed floors over single story lobby??? And since then, it’s became popular, making building taller, more supertall without building actual floors, without worry to rent out that space!!! And definitely this must be stopped. Mechanical floors must be spread out across whole building, or placed on the top of it. Why didn’t built extra floors, instead leave it as “mechanical void”, for what purpose, stick out like a angry finger over 300′-500′ feet maximum height neighbors, and this is a midblock, not like 750′ Times Warner Center, what actually have all their 55 floors built, not just raised up over empty space to make it look taller!!!

If new building prominent only like just being taller, that’s means definitely poor architectural design and overall appearance on ground levels. Some 15 story make you stop traffic within wall of simular height, just an example of Washington DC where is a zero highrises over 15 stories. And local architect making their new apartment and office block attractive by adding new types of construction materials, colors for cladding and making them unique for design on each block without making them taller!!! Look for outstanding example of 15 CPW it is a really gem architecture, a new standout classic, and taller of two towers are faced high rised streetscape of Broadway, while lower rise tower face Central Park West streetwall without compromise it with being outstandingly tallish!!!! This how we should built. Central Park West Streetscape not necessarily needed buildings taller than 300-400 feet. We don’t need to turn it in Streetscape of Central Park South with supertall spikes looming out. Leave Upper Westside area east of Broadway without buildings what being taller by just adding unbuilt space over it’s podium. Stop “mechanical void” scheme for building taller without actually built floors!!!

If the market wants height, what’s wrong with giving them height? People like the views. 1 WTC is an exception because the height was needed for the symbolism of renewal, etc.