Over the past 200 years, Broadway was the center stage for many that came to make their fortunes in the big city. Foundations for the world’s second Virgin Hotel, part of billionaire Sir Richard Branson’s Virgin Group, are underway at 1205, 1225, and 1227 Broadway, between West 29th and West 30th streets. The site’s relevance in the city’s history is rooted deeper than the new skyscraper’s supports. Before it housed the three 1920s office and retail buildings that graced the site until 2015, the block was home to a prominent theater row, a theater-museum built by John Banvard, once the world’s richest and most famous artist, and a number of other ventures worthy of remembrance and commemoration, undertaken by the gritty and relentlessly driven people that give New York its signature flair and energy.

A Growing Megalopolis

In 1771, five years before the thirteen colonies declared their independence from Britain, the population of the future five boroughs numbered around 22,000. The city of New York was limited to the area below present-day City Hall, barely larger than the boundaries established by the original Dutch settlement. The coming years would send the city on a trajectory of fantastic growth that would propel it to one of the world’s largest within a hundred years.

At the time, the majority of Manhattan consisted of farms and untouched woodlands, with the occasional settlement in between. Between 1780 and 1799, Caspar Samler spent $12,100 purchasing 37 acres of common land between what would eventually become 28th to 32nd streets, around the center of the island. The Commissioners’ Map of 1807 indicated three houses standing on the Casper Samler farm. Its homestead stood across the street from where Virgin Hotel rises today.

As the city’s combined population passed the 100,000 mark, its physical size grew to roughly twice as large as it was less than forty years prior. Its territory expanded mostly to the northeast, upon the new street grids that would eventually make up the Lower East Side. Expansion also took place to the northwest, in what is present-day Greenwich Village. The haphazard growth pattern was curbed when the Commissioner’s Grid of 1811 established a rigid framework for future development. A uniform grid of city blocks, roughly 200 feet wide, matched northward. Although their east-west length varied, it was invariably longer than the north-south run. The uniformity was broken only by the diagonal stretch of Broadway. It is commonly presumed to be based on the Native American Wickquasgeck Trail, although the actual trail rarely coincided with Broadway’s present run. During the following years, Broadway was at the vanguard of new development. By the 1830s, as the city’s combined population was approaching a quarter million, urban development crawled past Madison Square and past 30th Street, intruding into the domain of the Samler farm.

The first notable civic structure to grace the local blocks was the 1851 Marble Collegiate Church, which rose one block east of the Casper Samler farm homestead at 29th Street and Fifth Avenue. It was designed by Samuel A. Wagner in the Romanesque Revival style. To construction watchers, it is most recently known for selling its adjacent, 19th century Bancroft Building for demolition and redevelopment. But the church has also recently surfaced in the mainstream media as the church of preference for the presumptive Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump, who married Ivana Trump there in 1977.

However, the church and the morally pure message professed within its walls did not prevent the neighborhood from becoming the nation’s capital of vice in the coming decades. In 1859, Franconi’s Hippodrome, a performance venue with a 10,000-seat capacity, was torn down for the Fifth Avenue Hotel at 200 Fifth Avenue between 23rd and 24th Streets facing Madison Square. Although considered a folly at the time of construction, due to its distant location, it became the city’s premier hotel, serving as the social, cultural political hub for society’s elite. It boasted the first elevator in any hotel in the nation, powered by a steam engine that operated a revolving screw that passed through the center of the passenger cab. Each of its rooms included a fireplace, and, more notably, a private bathroom – an unprecedented convenience for the time. In 1860, a British reporter described the venue as “a larger and more handsome building than Buckingham Palace.”

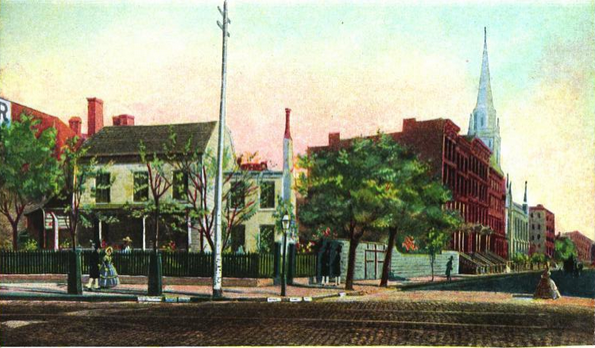

At this time, the city’s 1.5 million residents already made it one of the largest on Earth. Caspar Samler’s old homestead still stood at West 29th Street and Broadway, yet the surrounding farmland made way for a densely built district, with trolley tracks running down the middle of the cobblestone-paved Broadway.

Casper Samler homestead, West 29th Street and Broadway, looking east from the future Virgin Hotel site. Marble Collegiate Church is in the background. Henry Collins Brown. 1867. Public domain.

Prior to the Civil War, the city’s entertainment district, known as the Rialto, was located below 14th Street. The Fifth Avenue Hotel established its area as the latest destination for hotels, as well as other entertainment venues such as night clubs, saloons, dance halls, and casinos. In 1876, the district of nightlife and vice became known as the Tenderloin. The name was coined by New York Police Department Captain Alexander S. “Clubber” Williams, known not only for breaking up powerful street gangs, but also for a police protection racket involving local businesses. According to Williams, the red light district around Broadway supplied the juiciest bribes.

Between 1869 and 1871, the Casper Samler homestead was replaced with the eight-story, 300-room Gilsey House Hotel, designed by Stephen Decatur Hatch in the Second Empire style. The cast iron structure stands to this day, and is about to be restored to its former glory as part of the proposal to build a 64-story luxury apartment building to the east, at the site of the 19th century Bancroft Building.

Casper Samler Homestead at 1200 Broadway. Circa 1870. New York Public Library Digital Collections. Image ID 717378F

Gilsey House at 1200 Broadway, replacing the Casper Samler homestead. Circa 1900. New York Public Library. Record ID 624540

The Saga of John Banvard

In 1867, four years prior to the hotel’s grand opening and nine years before Clubber Williams compared local bribes to a juicy steak, a dramatic rags-to-riches-to-rags story unfolded across the street at 1225 Broadway, where the Virgin Hotel will rise 150 years later. This site was home to the theater museum of John Banvard, a showman, playwright, poet, historian, and the world’s richest artist of his time. Banvard was acclaimed by contemporaries such as Charles Dickens and Queen Victoria not only for his works such as the (allegedly) three-mile-long panorama of the Mississippi River, but also the theatrical flair that accompanied his work. Although little physical evidence remains of his once-copious labors, he blazed the trail for larger-than-life entrepreneurs, entertainers, art enthusiasts, and every other New Yorker willing to do whatever it takes to leave their mark, whether by honest, dishonest, or any other means necessary.

Portrait of John Banvard, circa 1855. John Hanners. A Tale of Two Artists: Anna Mary Howitt’s Portrait of John Banvard. Minnesota History, Vol. 50, No. 5 (Spring, 1987). Public domain. Image via Wikipedia.

Banvard was born in New York in 1915. By the age of fifteen, he would entertain the neighborhood youth with home-grown exhibits and performances, which he promoted with the flair of a circus ringleader. Even by that time, his “exhibits” were scientifically- and artistically-driven, featuring displays such as the “solar microscope,” “Camera Obscura,” and small panoramic scenes. A hydrogen experiment gone wrong literally blew up in his face and injured his eyes, yet even diminished eyesight did not stop the young man from pursuing drawing and painting. After his father’s death in 1831, he set off for the west, working at a drugstore in Kentucky and eventually making his way to the nation’s frontier at the Mississippi River. He became a stage set painter on a showboat, a traveling amusement ship of the kind that entertained frontier settlements up and down the river that were too small to set up permanent entertainment. After one season, he disembarked in New Harmony, Ohio, and founded his own traveling theater company, which he funded partially by swindling investors. Aside from unethical funding, he was not afraid to work hard for his art, serving as an actor, scene painter, director, and even a magician. For two seasons the company performed up and down the river valley, but soon Banvard grew tired of the life of a traveling, literally starving artist. He settled in Paducah, Kentucky, leaving his troupe just before they got themselves into a brawl that led to the death of a police officer.

In Paducah, Banvard was first introduced to working on “moving panoramas.” Growing up in Manhattan, he was already exposed to the displays consisting of moving canvas panels and atmospheric effects, a technique pioneered in France at the turn of the 19th century. His first two panoramas depicted Venice and Jerusalem on a long canvas. Mounted on two rollers and operated on one side by a crank, it created an illusion of movement. His third panorama, painted in 1841 and extending 100 feet, displayed “infernal regions.” After selling all three, the 27-year-old artist embarked on his largest project yet. He would spend the next two years traveling up and down the Mississippi River and its tributaries on a small boat. He made hundreds upon hundreds of sketches of the untamed wilderness of the continent’s interior and the beauty, dangers, and adventure he encountered along the way – the rolling green hills, riverside towns, brooding forests, friendly and unfriendly encounters with the locals and fellow travelers, and the river rogues looking to rob and harass (or worse) anyone they meet along the way.

By 1844, Banvard returned to Louisville, armed not only with the sketches but also with the stories that breathed life into the wild frontier. When he was not busy working odd jobs to make ends meet, the artist spent months laboring on his larger-than-life expression of what he saw in his 3,000 miles worth of river travels. The massive artwork was mounted on a system of rollers and hooks of Banvard’s own design, which he eventually patented. He would exhibit his work as he traveled along the river, annotating each show with a spirited narration of his adventures. Whether real or exaggerated, the tales brought alive the spirit of the diverse and wild frontier, the same spirit that captured the imagination of writers from Mark Twain to Ralph Waldo Emerson. In late 1846, the now-successful artist moved his show to Boston, one of the nation’s cultural focal points. Over the years, as his success grew, the artist would add new sections to the work. Eventually, whether the 12-foot-tall canvas stretched three miles as Banvard claimed, or “only” a quarter-to-half-a-mile-long, as scholars such as John Hanners allege, the Mississippi River Panorama became the world’s longest painting.

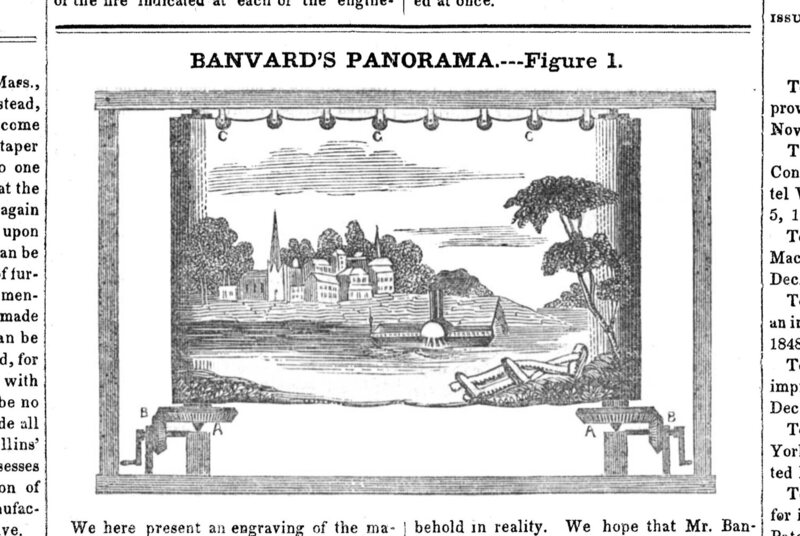

An excerpt from the Scientific American, 16 December 1848. Source: Wikipedia via Atlas Obscura

Advertisement for Banvard’s Mississippi panorama at Amory Hall, Boston, 1847. Public domain. Source: American Broadsides & Ephemera, Series 1, via Wikipedia.

With time, Banvard fine-tuned his performance. The display was illuminated with creative lighting, and the roller machinery was now hidden from view. Its mechanical noise was concealed with a series of piano waltzes by Thomas Bricher, specifically commissioned by the artist. Bricher went on to marry Elizabeth Goodman, the young pianist he hired to perform them. This literal take on the “motion picture” was the closest thing the middle of the 19th century had to a moviegoing experience, taking the viewer on a trip to distant and exotic lands without an extensive cast of live actors.

From that point, Banvard’s success ballooned exponentially. The final Boston show inspired the governor, the speaker of the house, and Massachusetts state representatives to pass a resolution to honor the artist. In 1847, he moved the show to New York, by which time his fame and wealth inspired imitation. Would-be competitors sat in the audience, feverishly sketching what unfurled before their eyes. For instance, John Rowson Smith would soon display his “Four Mile Long Mississippi Panorama.” In 1848, after making it big in his city of birth, Banvard moved his performance to England. There, he easily multiplied his success. His London show ran for 20 months and accommodated over 600,000 spectators during its run. Even the show’s musical score became a hit at local establishments. In his letter to the artist, Charles Dickens admitted that he was “in the highest degree interested and pleased” by the performance. He eventually earned praise from Queen Victoria when he put on a private show for Her Majesty in Windsor Castle the following year. Banvard spent two more years replicating his success in Paris. At one point he “franchised” his show, painting a second panorama of “the other side of the river” and displaying it in other cities.

John Banvard presenting his panorama to Queen Victoria. 1849. John Hanners. A Tale of Two Artists: Anna Mary Howitt’s Portrait of John Banvard. Minnesota History, Vol. 50, No. 5 (Spring, 1987). Public domain. Via Wikipedia.

During his stay in Europe, he continued exploring scientific pursuits, frequently visiting museums and eventually becoming an avid Egyptologist. He made a trip to what was then known as Palestine, which was the subject of one of his first panoramas, and sailed up and down the Nile, collecting historical artifacts and painting yet another panorama along the way.

Upon his return to the United States in 1852, Banvard was likely the world’s richest and most famous artist. He fashioned his new Long Island mansion as a replica of Windsor Castle, situated on a 60-acre property and staffed by numerous servants. He called his new residence Glenada, though the neighbors referred to it as Banvard’s Folly, where he stored his now-large collection of historical artifacts. In 1861, as the country was torn apart by the Civil War, Banvard supplied the Union army with his hydrographic charts of the Mississippi River, earning praise from General John Fremont. In the same year he became the first American to produce a printed color picture via chromolithography, which uniquely copied both the color and the canvas texture of the original image. By 1964, his historical drama “Amasis, or, The Last of the Pharaohs,” ran in Boston to high critical acclaim.

But while Banvard easily stayed ahead of lesser imitators, his status as a leading showman was usurped by P.T. Barnum. Barnum opened a new museum on Broadway and Ann Streets opposite City Hall after the first one, built in 1842, burned down in 1865. Not to be outdone, Banvard purchased a mid-block lot at 1225 Broadway between West 29th and West 30th streets, in the center of the city’s latest, emerging entertainment district.

Former Banvard’s Museum, converted into Daly’s Theatre by the time of the photo was taken around 1900. Source: New York Public Library. Image ID 717385F

June 17, 1867 marked the opening of the 40,000-square-foot “theater museum,” the largest and arguably best museum in all of New York. The five-story building was fronted with a colonnaded portico, lined with a full-length balustrade above the third floor, and topped with a two-story mansard roof with round windows.

The painting would be exhibited in a 2,000-seat auditorium, becoming the first permanent home for the well-traveled artwork. Smaller lecture halls displayed the artifacts acquired by Banvard on his journeys. The building was designed to supply efficient ventilation, which was a crucial feature in the pre-air-conditioning era of stuffy public halls. Unfortunately, the larger-than-life artist finally bit off more than he could chew. As Banvard spent his adult life as a traveling performer, he was woefully inexperienced when it came to managing a permanent venue, with its staffing and maintenance issues and costs. In addition, it was financed with $300,000 worth of stock that Banvard used to pay the investors and builders. Whether it was a swindle or an amateur mistake, Banvard failed to register the stock with the New York Stock Exchange, making it worth less than the paper it was printed on. Lastly, Banvard did not have what it took to take on the P.T. Barnum juggernaut. Though many of Barnum’s exhibits were either of questionable authenticity or outright fraudulent (including his “Nile Panorama” which was likely copied from Banvard’s own), Barnum’s indomitable ability for self-promotion steamrolled all competition. Banvard’s museum closed its doors on September 1, just ten weeks after opening.

The museum set off a chain reaction that reduced the world’s richest artist to poverty and infamy within mere years. Banvard’s investors were outraged when they discovered that their shares of stock were worthless, and no one would ever trust the artist with money again. One month later, the building reopened as Banvard’s Grand Opera House and Museum, yet none of its stage performances were successful. He was forced to close again and lease the space to third parties. Banvard reopened his venue a third time as the New Broadway Theatre. Its stage housed Banvard’s latest play – “Corrina, A Tale of Sicily,” which was soon discovered to be plagiarized from a still-living playwright.

After several failed attempts (including a humiliating refusal from his nemesis, P.T. Barnum himself), Banvard finally sold the building in 1879. One of Banvard’s last literary successes was titled “The Origin of the Building of Solomon’s Temple,” which was published in 1880. By 1883, to pay off the numerous creditors, the bankrupt artist sold almost all of his possessions, including the Glenada estate, which was promptly torn down. Just about the only thing the artist still had to his name was his magnum opus, the now-worn Mississippi Panorama. The artist and his wife, near-penniless in their late 60s, moved back to the frontier, which had by then shifted to South Dakota. There, in Watertown, they lived at their son’s house, who was a local lawyer. Under the pen name of “Peter Pallette,” Banvard became South Dakota’s first published poet, even if only a few of his 1,700-plus poems saw publication. In his final years, despite his growing frailness and worsening eyesight, the artist went for his last hurrah. He painted one final panorama, titled “The Burning of Columbia” in commemoration of General Sherman’s destruction of the South Carolina capital in 1865. The old man gave a spirited performance to great critical acclaim, and passed away on May 16, 1891 at 75 years of age.

Back in New York, Banvard’s former museum became Daly’s Theatre in 1879. It was run by Augustin Daly, America’s first recognized stage director, who doubled as a drama critic, theatre manager, and playwright. The venue was successful enough to be considered America’s foremost theater in the period between 1879 and 1899. Its stage has seen performances from Broadway theater pioneers such as Joseph Haworth, to international acts such as the Russian actress Vera Komissarzhevskaya.

The Tenderloin Arrives

The entertainment district continued its northward creep, now extending to the high 30s, geographically speaking. By that time, the Tenderloin held a well-established reputation. The vibrant entertainment district was a true cultural melting pot, with offerings ranging from world-class opera to gambling halls and prostitution parlors, and attracting everyone from the nation’s elite to the common felon in equal measure. In 1883, the Metropolitan Opera House opened at 1411 Broadway, between West 39th and West 40th streets. With capacity for 3,849 attendees, the space became one of the grandest theaters in the nation. By the mid-1880s, some of the city’s greatest stores, hotels, and clubs were located in the vicinity, with much of the city’s upper-class elite living around the adjacent blocks, particularly east of Broadway. The theater district extended up and down Broadway between 23rd and 42nd Streets, where it was known as “The Line.” In December 1880, the stretch between Union and Madison squares became one of the first electrically lighted streets in the nation, bathed in nighttime light by Brush arc lamps powered by a nearby facility at 133 West 25th Street.

Local theater owners were quick to adapt the innovation to promote their venues. By the 1890s, electrical advertising signs became a mainstay along Broadway between 23rd and 34th streets, earning it the nickname of “The Great White Way.” Such lights decked out the façade of Palmer’s Theatre, later renamed to Wallack’s Theatre, which opened in 1888 at the northeast corner of Broadway and West 30th Street. In 1892, the Imperial Music Hall opened at 1223 Broadway next door to Daly’s Theatre. The venue gained popularity after it was leased to the vaudeville comedy team of Joe Weber and Lew Fields in 1896. The Weber and Fields Broadway Music Hall staged an array of comedies, musicals, vaudevilles and burlesques, the latter of which frequently ran as risqué versions of popular Broadway shows. The theater was modest in size, with a front façade barely larger than that of an average townhouse, but it made its presence felt through a festive, bombastic Beaux-Arts façade, set between a pair of neo-Classical columns and adorned with a dazzling array of electrical lights.

Weber and Fields Broadway Music Hall. 1903 or 1904. International News Photos. New York Public Library Digital Collections. Image ID 711931F

The blocks immediately west of the Great White Way provided a raunchier scope of entertainment. An almost-continuous row of brothels lined West 29th Street west of Gilsey Hotel and Daly’s Theatre, serving a broad range of clientele. Affluent locals, as well as well-to-do city visitors looking for a wild night, would flock to richly decorated venues where they would be served by the ladies of the night as well-versed in high culture and etiquette as they were in the arts of bodily pleasures. When Luc Sante described the neighborhood in his 1991 book “Low Life,” the author noted that one block south of the red light block at West 29th Street, West 28th catered to high-end gamblers, while West 27th served their less affluent counterparts. Sante also noted that saloons and short-stay hotels, common in red light districts, dotted the adjacent blocks. In all, the seediest establishments were generally confined to the blocks between Broadway to the east and Sixth Avenue to the west, starting around West 24th Street and stretching about fifteen blocks north.

The Broadway block between West 29th and West 30th streets, west side. H. N. Tiemann. Urbrock Collection. Around 1905. Source: New York Public Library. Image ID 717386F

The most notorious of the nighttime haunts stood next door to Daly’s Theatre. The Argyle Theater first opened in 1872 on the southeast corner of the intersection of Sixth Avenue and West 30th Street. In 1878, the Sixth Avenue elevated line brought rapid transit into the neighborhood. The same year as the el cast its shadow over the street, the theater owners embraced the shady side of the entertainment business. Now known as the Haymarket, the venue became the city’s top destination both for rowdy performances and the ladies of the night that were common in the audience, ready to solicit the gentlemen also in attendance. By the 1890s, the city’s liveliest party, described as “New York’s Moulin Rouge” by the Bowery Boys historical blog, would often spill out onto Sixth Avenue beneath the el and West 30th Street to the north, while the police got their “cut of the tenderloin” to look the other way.

Tenderloin street party on Sixth Avenue. Image from Ephemeral New York via boweryboyshistory.com. Date/author unknown.

Though the theater opened chiefly onto Sixth Avenue, a 1911 New York Times article confirms that the 12,055-square foot property was triangular-shaped, with its narrow end extending all the way to Broadway. Sitting adjacent to Daly’s Theatre, the corner was occupied by a five-story townhouse with retail at ground level and a mansard roof making up the top floor.

Even the local dining establishments were often themed as fantastical entertainment, similar to the tourist hangouts of Times Square today but with a rowdier, more authentic edge. August L. Janssen’s Hofbrau Haus, one of the city’s most famous German eateries of its time, sat across the street from Daly’s, at 1214 Broadway, one door south of West 30th Street. Like the establishment inside, the exterior of the five-story building stood as a whimsical mix of old world tradition and new world innovation. Its tall, illuminated marquee pasted upon the distinctly Northern European façade. Since 1898, its slogan “Janssen Wants to See You” had greeted New Yorkers and city visitors alike. The ringing of the bell announced when a new keg was tapped to ensure that at least 30 were kept on tap at any given time.

Janssen’s Hofbrau House, center-right. Looking east from West 30th Street across Broadway. Percy Loomis Sperr. January 9, 1928. New York Public Library Digital Collections. Image ID 717382F

In many ways, the neighborhood was a microcosm of what New York, the soon-to-be-world’s-largest-city, would symbolize for much of the 20th century, with glamor, highbrow culture, vice, immorality, and crime coexisting side-by-side. This energetic mix that exemplified some of the best and the worst that humanity had to offer. The 1998 Landmarks Preservation Commission report on the castle-like 23rd Precinct police station house at 134-138 West 30th Street, built in 1908 one block west of Daly’s Theatre, credited the 1885 neighborhood for having some of the city’s greatest theaters, hotels, clubs, and shops, yet also described its streets as rife with crime, as expected of the district where “at least half of the buildings were devoted to some sort of wickedness.” Reverend Thomas De Witt Talmage denounced the entire city of New York as “the modern Gomorrah” for allowing such a den of iniquity to exist.

The incredible diversity of the local streetscape was further underlined with one of the city’s premier African-American districts, situated roughly between West 28th and West 32nd streets and stretching from Sixth to Eighth avenues. In contrast to the seedy district immediately east, the neighborhood’s residents belonged chiefly to the middle class.

End of an Era

As it entered the 20th century, the city blossomed as rapidly as ever. Tall buildings, confined to the island’s southern tip until recent years, made their way uptown. By the time the 12-story Breslin Hotel rose across the street from Gilsey House, catty-corner to 1223 Broadway, a number of similarly-sized office and hotel buildings had sprouted along the Great White Way. Despite its rising skyline, the Tenderloin was about to lose its prominence as an entertainment district. Within a decade, the neighborhood would lose most of its entertainment venues, both of the high-class and lowbrow variety. Despite remaining a vibrant commercial district, the neighborhood would enter a century-long spiral of general decline that would end only a few years prior to the time of this writing.

Broadway in December 1904. Daly’s Theatre is on the left. Geo. L. Balgue. Source: New York Public Library. Image ID 717377F

The reasons for this shift are complex. The unrelenting uptown crawl of the city’s adult playground both created and eventually killed off the Tenderloin. As mentioned earlier, the city’s pre-Civil War nightlife revolved around the Bowery and the Rialto districts below 14th Street. Real estate pressure driven by rising land values, as well as the pioneering development of a few key anchor hotels and entertainment district, made the block of Broadway between West 29th and West 30th streets into the epicenter of the city’s hottest amusements. Now, the same pressures have forced similar development along the blocks further north, anchored along 42nd Street and the bowtie-shaped crossing of Broadway and Seventh Avenue still known as Longacre Square at the time. As Timothy J. Gilfoyle describes in The City of Eros, by the 1890s, the title of “the most sinful street in the city” passed from West 29th to West 39th Street. That block became known as Soubrette Row for its “flirtatious” ladies and the “scandalous services” they offered. By 1901, a similar district would spring up further north along West 43rd.

The first drastic blow to the neighborhood came on August 13, 1900, when the it became the stage for the city’s worst riot since the 1863 draft riots during the Civil War, which decimated the local African-American community. As May Enoch, a local African-American resident, was waiting on the street for her fiancé, Arthur Harris, plainclothes officer Robert J. Thorpe accused her of prostitution and placed her under arrest. Worried by her cries, Harris ran out of the neighboring saloon. In the ensuing argument, Thorpe struck Harris with his billy club, to which the man retaliated with a knife. As Thorpe was dying of the stab wound, Harris fled the scene. A peaceful daytime vigil at the officer’s home on 37th Street and Ninth Avenue turned violent in the evening, when the mob, drinking heavily and shouting racial slurs, went on the offensive against local residents. Hundreds of rioters, including some police officers, moved through the streets, assaulting every African-American man and woman they would come across, battering them with fists and stones. The victims would be pulled out of local restaurants and streetcars, to be assaulted in the middle of the street, as the rioting spread to Eighth and Seventh avenues.

Hundreds of responding police eventually beat the crowd into submission, but few arrests were made, and the ones did take place involved the victims on more than one occasion. At one point, the officers observed a brutal beating of Alexander Robinson, who was pulled out of a passing streetcar, yet intervened only when the rioters were about to lynch him on a nearby lamppost. No charges were pressed in the incident. Over the next month, scandal brewed of the police handling of the riots, with numerous accusations of police brutality, yet all charges were eventually dropped. A New York Tribune cartoon showed a tiger, the mascot for the corrupt Tammany Hall political cabinet, dressed in a police uniform and swinging a bloody billy club while standing next to a bleeding African-American man. “He’s on the police force now,” the caption read. The local residents’ formation of the Citizens’ Protective League was insufficient to protect the community from further harassment. In the coming years, New York’s most prominent African-American neighborhood disintegrated as its residents moved uptown to San Juan Hill (now Lincoln Center) or Harlem. And as it often happens in riot-ravaged districts, the terror and tension drove down the desirability of all surrounding blocks.

Further east, the theater district was buckling under the growing competition from the larger and grander performance halls further up the Great White Way. The Empire Theatre’s 1893 opening at 1430 Broadway between 40th and 41st streets was followed by the much larger Olympia Theatre on Broadway and West 44th two years later. In 1904, Times Tower, the new headquarters of the New York Times, opened between Broadway and Seventh Avenue and 42nd and 43rd Streets, as the city’s second-tallest building. It towered at the south tip of the narrow intersection, which was renamed Times Square soon after it started hosting the city’s grandest outdoor New Year’s celebration. In the same year, the skyscraper would face the massive and lavish Hotel Astor, which established the neighborhood as an entertainment destination as effectively as the Fifth Avenue Hotel established the Tenderloin district decades ago.

The city’s first underground subway line opened at the turn of the century. However, it had to be separated in two sections. While the line ran along Broadway above 42nd Street, it shifted east to Grand Central Depot in its south run to City Hall below 42nd Street. The reason for this awkward alignment was that, in the 1890s, Tenderloin community opposition ensured that the line did not run along Broadway south of 34th Street. The obstructionists did not realize that they were destroying their own future prospects. Times Square, which was now serviced by a new subway station, became the more convenient location for visitors. The underground station carried all the advantages of rapid transit without any of the inconveniences of the Sixth Avenue elevated line, which had serviced the Tenderloin since 1878. The last trains rumbled on its raised tracks on December 4, 1938. The neighborhood finally saw underground subway service when the 28th Street station on the BMT Broadway Line opened on January 5, 1918.

The station opened too late to preserve this stretch of Broadway as a viable cultural district. The Weber and Fields Broadway Music Hall at 1215 Broadway held its last show in September 1905, closing after the Weber and Fields team splits up. Renamed Weber’s Music Hall, the venue lasted until January 1913 and was demolished in 1917. The Haymarket on the other side of the block was converted into a movie theater between 1915 and 1916, and was torn down not long after. Standing between the two, the Daly’s Theatre building, built by John Banvard in 1867, was reduced to rubble in the same time frame.

By 1920, the entire Broadway blockfront between West 29th and West 30th streets was a blank slate. The three new buildings at 1205, 1225 and 1227 Broadway were all built in the early 1920s. All three read as a single ensemble thanks to matching beige brick facades and a uniform street wall, while their differences in bulk and detailing provided streetscape variety. Their combined 135,000 square feet of floor space consisted of more than a dozen ground level shops, with additional shop space, offices, and storage located on the floors above.

1205 Broadway at the corner of West 29th Street was the shortest of the group but had a large footprint, with its seven shops taking up almost half of the Broadway blockfront. Its windows were arranged in wide bays, and the cornice was decorated with a simple brick pattern and white stone trim at the parapet.

1205 Broadway (left), 1225 Broadway (center), and 1227 Broadway (right). Credit: Venture Capital properties.

Sitting within the Banvard Museum/Daly’s Theatre footprint, the mid-block 1225 Broadway stood nine-stories-tall. Its lower three floors were faced with a Neoclassical colonnade, with six levels of plain, brick-faced office floors above. They were almost certainly capped with a cornice at one point, as evidenced by a mismatched, plain brick parapet evidently added at a later date.

1227 Broadway stood on a trapezoidal site at the intersection with West 30th Street, replacing the Haymarket property. The four-story building was very similar in size and purpose to its predecessor. Ads, windows of varying sizes, and a fire escape rose above the glass storefronts of the lower two floors.

Similar commercial transformations took place all over the surrounding blocks. The Gilsey Hotel across the street was converted into office space between 1910 and 1916, marring the lower floors of the façade. By 1931, the Hoffbrau House up the block, as well as Wallack’s Theatre one block north, were replaced with office structures, as well. Rows of roughly 20-story-tall buildings now marched up and down the local blocks, massed in the “wedding cake” style to conform with the new zoning regulations.

Gilsey House after its office renovation. Percy Loomis Sperr. 1920. Source: New York Public Library. Image ID 717376F

For the remainder of the twentieth century, the neighborhood remained a bustling yet seedy district at the periphery of more successful neighborhoods on all sides. Until recent years, the blocks still had some of the highest crime rates in Manhattan. By the time the three buildings at 1205-1227 Broadway faced demolition in late 2014-early 2015, all three were well past their prime, with soot stains, chipping paint, drab blue awnings, and occasional structural alterations marring their facades. Still, their narrow storefronts, which measured 20 feet and less, resulted in high retail density and made for a dynamic pedestrian stretch.

1205, 1225 and 1227 Broadway. Looking northwest from West 29th Street and Broadway. Left: August 2013 (image from Google). Right: January 2015

Like many formerly-seedy districts all around the city, the area is undergoing a renaissance. In the late-2000s, the pedestrian space on Broadway was expanded and a bike lane was added at the expense of a traffic lane. While the area retains its commercial appeal, it increasingly caters to a higher category of retailers. The Broadway block now resembles its look from both mid-1860s and 1920, as its site is once again cleared for new construction. It will become home to a 38-story, 460-room Virgin Hotel. The building, which goes by the address og 1227 Broadway on its permits, is designed by VOA Associates and anchored by a multi-level retail complex at ground level. On the other side of the block, the Haymarket site at 846 Sixth Avenue is about to welcome a 24-story tower. The former Tenderloin district prepares to enter its latest phase, one that would hopefully maintain its vibrant activity without the darker aspects.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

Million Bravo for this marvelous article

I guess “whoop dee doo” could still be said without sarcasm being inferred in 1903.

I don’t agree.

Friendly, Mia

Really enjoyed your story — I came across it while doing research on the Gilsey House.

In 1810, James A. Stewart, a wealthy wine merchant, owned the adjacent property bounded by 29th and 31st streets, the Bloomingdale Road (Broadway), and the Fitz Roy Road (near today’s 8th Avenue). A wide, diagonal street called Stewart Street intersected his property. Stewart asked the Common Council to accept Stewart Street as a public road, but it was thought that the diagonal road might interfere with the the new grid plan then under consideration (the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811).

Stewart Street was eventually reorganized into conventional lots. However, the buildings on the north and south sides of 30th Street between 6th Avenue and Broadway followed the original diagonal, hence the trapezoidal site at 1227 Broadway. Of course now all those buildings on the south side of 30th Street have been demolished to make way for the Virgin Hotel, and so eventually the old diagonal that was once Stewart Street will be gone. If you look on Google Earth, you can still see the diagonal. Or check it out in my story about the Stewart estate: https://hatchingcatnyc.com/2016/12/29/hero-new-york-city-fire-cat-chelsea-part-ii/