Some of the most densely populated neighborhoods in Queens are nestled along its eponymous central arterial roadway, 7.2-mile-long Queens Boulevard. However, around its midsection, between Grand Avenue/Broadway to the east and Greenpoint Avenue/Roosevelt Avenue to the west, the subway temporarily veers north of the 200-foot-wide the thoroughfare. This portion is much less developed than neighborhoods on either side. Apart from a dense residential cluster in central Woodside, almost all of this stretch is decidedly anti-pedestrian and thinly developed, replete with low-slung commercial properties, such as auto shops and parking lots. The 11-story, residential Elmhurst Building, on which construction is wrapping up at 70-32 Queens Boulevard, now stands as the tallest on a two-mile stretch of the boulevard between Rego Park and Woodside. Although modestly-sized by the standards of the city skyline, the solitary stack towers like a Saguaro cactus over a desert. However, change is in the air as a wave of development is sweeping the area. Enabled by a 2006 neighborhood upzoning and fueled by an acute housing shortage, the new projects will transform the barren district into the urban neighborhood that it ought to be.

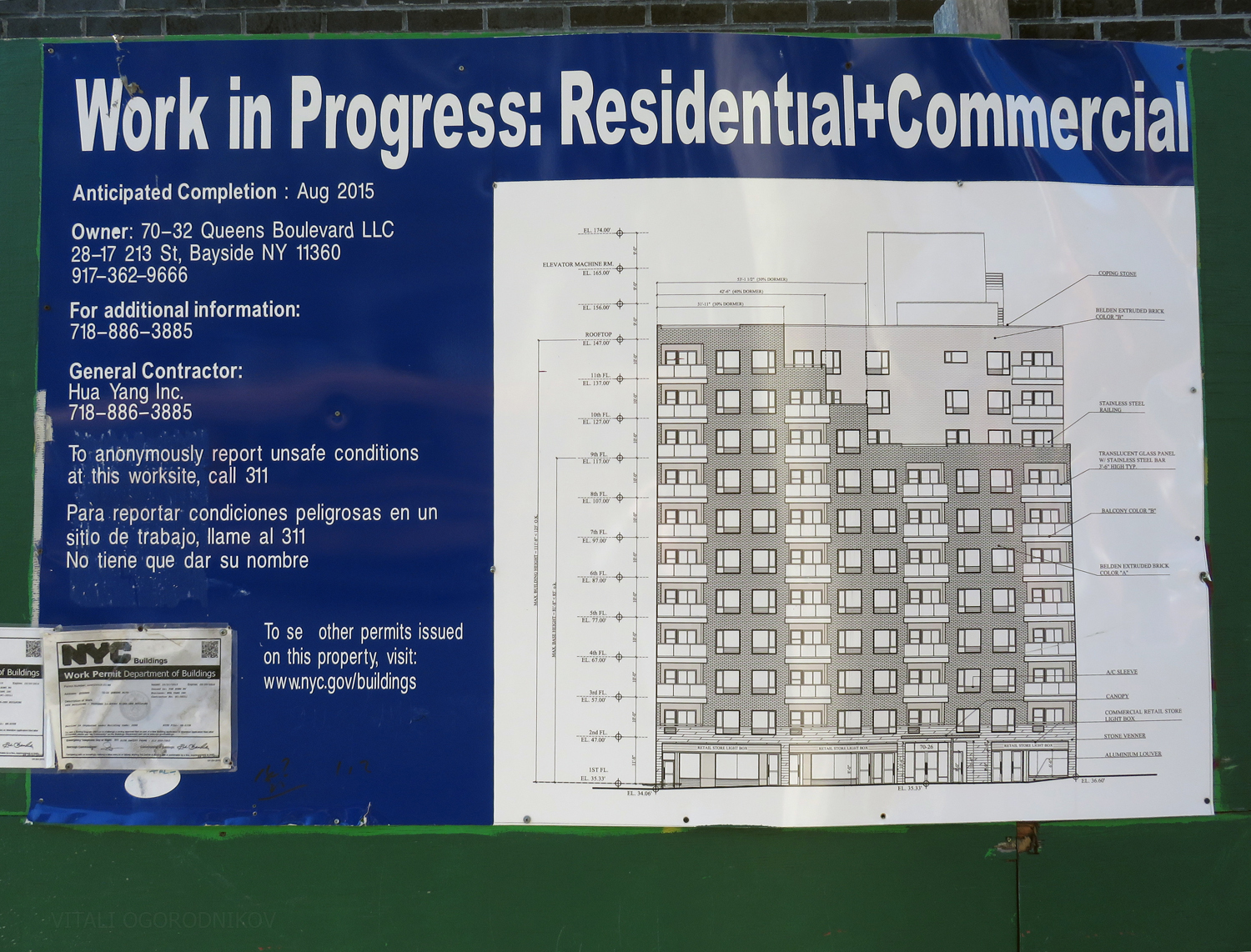

The building, designed by Michael Kang Architect, is a near-perfect embodiment of the current zoning limits. Although the decade-old upzoning boosted the buildable potential, it retained surprisingly restrictive height and bulk limits, even despite the local abundance of both public transit and expressway access, as well as the extreme width of Queens Boulevard. The building rises almost 112 feet from the front entrance to the roof level, which falls a few feet short of the 125-foot height limit. The top of the structure rises 139 feet high, but the service bulkhead is excluded from the zoning restriction. Similarly, the main street wall rises uninterrupted for almost 82 feet, stopping short of its 85 foot limit. This requirement is observed, but only partially. The eastern portion of the façade rises above this line in three setbacks. This is permitted since it is classified as a dormer, which is allowed to break the setback line. Even though the western wall, which directly faces Midtown Manhattan, is windowless, the building’s prominent height would allow for sweeping vistas across Queens, with glimpses of the Downtown Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan skylines from the south windows and the Upper East Side from the north ones.

The boulevard-facing ground floor, which would be clad in a stone veneer, is slated to contain 5,500 square feet of retail space, a 180-square-foot community facility, and the entrance to the 59-car garage. Sixty-nine residential units, spread across 55,000 square feet of space, comprise the 10 stories above, which are faced with extruded Belden brick. The front façade is lined with four bays of balconies, while the rear boasts three more. Although initial plans called for 42-inch-high translucent glass balustrades, the final product features metal railings instead. There is no cornice, aside from a thin line of stone coping that matches the window sills.

As evidenced by the building’s blank side walls, the structure is meant to function as a part of a greater street wall. Although, at the moment, nothing is proposed for the adjacent lots, they are likely to see new development sooner rather than later.

The bulk of the structure sits on the boulevard, while the a single-story base faces the residential neighborhood to the south. Though its near-windowless wall is unfortunate, its scale respects the established, low-rise context.

At this point, Queens Boulevard separates Maspeth to the south from Elmhurst to the north. Yet despite this official delineation, Maspeth is generally assumed to lie somewhat to south, while the boulevard-adjacent blocks are usually seen as Elmhurst. In deference to this trend, the developer’s building page labels the project as the Elmhurst Building, despite its position on the Maspeth side of the boulevard. Moreover, Elmhurst is home to an ever-growing Asian community. Chinese businesses and residents in particular are arriving in ever-increasing numbers, as the community in nearby Flushing is stretching the local real estate to its limits. To the east of this location, Flushing-based developers are already lining the boulevard with mid-rise residential properties. Shop signs in Mandarin and Cantonese are becoming an increasingly common sight. From this real estate perspective, “Elmhurst Building” sounds more appealing than “Maspeth Building.”

The project’s Flushing associations are easy to spot. Though the developer, Steve Cheung, owns properties all around Queens, the architect, Michael Kang, tends to specialize in Flushing real estate. The general contractor in charge of the project is Flushing-based Hua Yang Inc. The website of the realtor, Happy 8 Realty, offers a bilingual option and sits under a banner that switches from English to Chinese. Even the realtor name is based on the number considered lucky in many Asian cultures.

Roughly a quarter of the building’s budget was financed with the EB-5 visa program, which provides a green card to foreign nationals that invest at least $1 million in the U.S. while creating at least 10 jobs. Though the media loves raising alarms about foreign investors, we see their obsession as misguided and unproductive. This city, which objectively ranks among the greatest in the world, has been driven by foreign investors ever since Dominican-Dutch trader Juan Rodriguez wintered in Manhattan in 1613. When Captain Cornelis Jacobsen May settled a handful of Dutch Walloon immigrants on Governors Island, then known as Nut Island, in 1623, they arrived under a Dutch economic incentive program functionally similar to today’s EB-5.

Of course, it is hard to compare the Walloon frontier to the Elmhurst one, even in a figurative sense. Despite the decidedly auto-oriented commerce on this stretch of Queens Boulevard, established residential neighborhoods line the quiet streets both to the north and to the south. Traditional urban models tend to feature lower-density blocks, centered around wide avenues and boulevards lined with shops and larger buildings. While the supporting residential blocks have been present for decades, a high-density core around the central boulevard is sorely missing.

However, drastic changes are on the way. A nine-story apartment complex is proposed at 46-02 70th Street at the eastern end of the block. On the other side, half a block west, Madison Realty Capital is assembling a block-wide lot at 69-02 Queens Boulevard, which would allow them to construct anywhere between 145,000 and 358,000 square feet. Across the boulevard, where 45th Avenue joins Queens Boulevard, a site has been cleared for the impending construction of the seven-story 70-09 45th Avenue. Across the street from the Elmhurst Building, an assemblage of properties at 72-01 Queens Boulevard is also in play. A few blocks west, in Woodside, on the other side of the complex junction where the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and the Long Island Rail Road cross the boulevard, the eight-story 65-15 Queens Boulevard is nearing completion. Two more mid-rises are underway across the busy thoroughfare at 64-06 and 64-26 Queens Boulevard.

The ongoing development frenzy is long overdue. The micro-hood, at the junction of Elmhurst, Maspeth, and Woodside, sits within a 15-minute walk from three stations on the 7 train – 61 St, 69 St, and Roosevelt Av-Jackson Heights. The latter, which is the closest one to the Elmhurst Building, is also serviced by the E, F, M, and R trains. Vibrant dining and nightlife revolves around the subway stations. The Woodside station on the Long Island Rail Road connects to the 61 St station. All these options put Manhattan within a 20-25 minute commute. Getting to Manhattan via bus or car via Queens Boulevard and the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge takes about as long. These varied commute options, as well as the enormous 200-foot width of the boulevard, make it perfect for high-density development. If anything, the 125-foot height limit established by the 2006 upzoning is absurdly low, stunting the opportunity for growth at a high-potential site in a housing-starved city. While bulk restrictions, which prevent developers from overtaxing existing infrastructure, are understandable, there is absolutely no reason for the low height limit at this location. If anything, a tall building with the same number of residents as a shorter, squatter one might open up space for, say, a public plaza, the likes of which are sorely needed in this neighborhood.

Of course, large buildings alone do not make a neighborhood. While ground-level retail, such as that at the base of 70-32 Queens Boulevard and other nearby developments, would go a long way to animate the pedestrian realm, the city must also do its part to make the area more livable. Since this stretch of the boulevard has prioritized the motorist for many decades, its streetscape must be re-configured if it is to accept an influx of residents. Fortunately, the block presents opportunities to create viable public space with relatively little cost and effort without any sacrifice on behalf of the drivers.

The Elmhurst Building rendering shows a pedestrian overpass spanning the boulevard. This addition is pure fantasy that does not represent any actual plans. However, it emphasizes a real problem at the site. The nearest crosswalk sits at 70th Street, 250 feet west of the new building. There is no other crossing for nearly 2,000 feet to the east, where a crosswalk along Jacobus Street connects the two sides of the boulevard. Having nearly half a mile separating two street crossings is absurd. A cohesive residential neighborhood cannot function with such an impenetrable, anti-urban barrier running down the middle. Since the overpass suggested in the rendering is too intrusive and expensive to be taken seriously, we suggest introducing a crosswalk at 73rd Street, about halfway between the two existing crossings. Ideally, there would be another one at 72nd Street, closer to where the Elmhurst Building stands.

There is not a single crossing from this point to the furthest end of the boulevard visible in this picture

The new crossing would not only connect the separate halves of the neighborhood, but it would also provide access to the wide medians splitting the boulevard, which ought to be landscaped as public space. Across the street from the Elmhurst Building, the boulevard’s four express lanes, two in each direction, are separated with a 15-foot median. Aside from a few, widely spaced trees, the median is barren and inaccessible. Similarly barren side medians separate the express lanes from single-lane service roads by the sidewalk. Substantially wide, each measures 30 feet across, if ones is counting the recently introduced bike lanes. 400 feet to the east, adjusting to the supports of a train trestle, the boulevard changes configuration. There, the central median is reduced to a simple concrete barrier, while each of the side medians expands to roughly 37 feet in width. As such, they are sufficiently roomy enough to support viable community space, though they are fenced off and inaccessible at this point. Since the next phase of the ongoing boulevard redesign will address the Elmhurst portion, we hope that the final design succeeds in creating effective public space rather than merely re-shuffling existing unused surfaces. As hundreds of families are about to move onto either side of the boulevard, it is time for the city to transform the barren eyesore into a green front yard for the brand new community.

In yesterday’s update about the nearby 70-09 45th Avenue, we made a case for creating another, 3,700-square-foot public space by converting an erroneous traffic lane at the 45th Avenue intersection. For an in-depth look at how the intervention would benefit the community without inconveniencing the drivers, see the last portion of the article.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

“The nearest crosswalk sits at 70th Street, 250 feet west of the new building. There is no other crossing for nearly 2,000 feet to the east, where a crosswalk along Jacobus Street connects the two sides of the boulevard.”

I assume the author came to this conclusion after looking at an outdated map. There actually is a crosswalk between 72nd and 73rd streets, but it was installed relatively recently—I’d guess no more than a year ago, although I can’t be precise.

https://www.google.com/maps/@40.7393757,-73.891472,19z

“At this point, Queens Boulevard separates Maspeth to the south from Elmhurst to the north. Yet despite this official delineation, Maspeth is generally assumed to lie somewhat to south, while the boulevard-adjacent blocks are usually seen as Elmhurst. In deference to this trend, the developer’s building page labels the project as the Elmhurst Building, despite its position on the Maspeth side of the boulevard.”

Very incorrect. Maspeth ends at 52nd Avenue. North of that is Woodside. When you pass east-west under the CSX tracks, you are crossing from Elmhurst to Woodside. Maspeth does not touch Queens Blvd.

The building lined itself from the neighborhood, become tallest in one of the new construction.