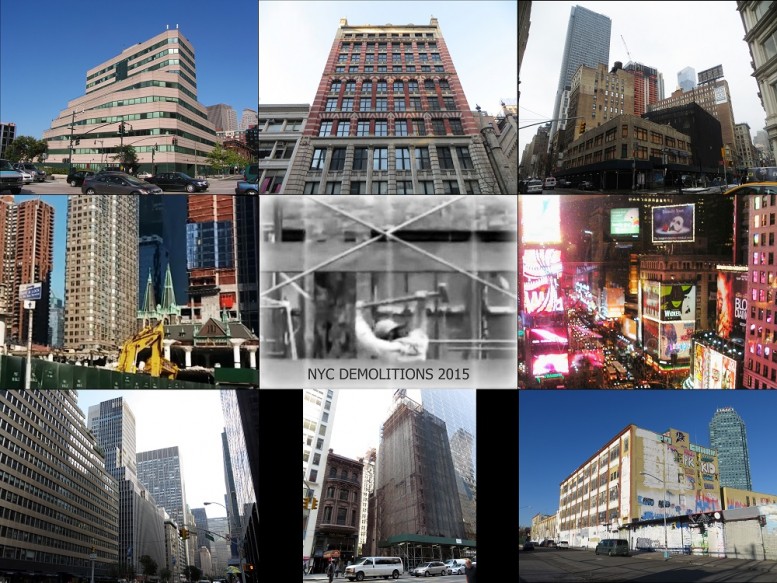

In 2015, New York’s landmarks law turned 50 years old. Events and discussion panels were held across the city throughout the year. The Museum of the City of New York held the commemorative Saving Place exhibit. As YIMBY reported, six individual landmarks and four historic districts were designated during this period. However, last year also saw its fair share of demolitions. Here, we look back at a small selection from the dozens of buildings that met the wrecking ball over the course of 2015. These eight structures range from architectural masterpieces to eyesores and span across a variety of decades, styles, and uses – as diverse as the Big Apple’s built environment itself.

The projects are ordered roughly from the south to the north of Manhattan, with the Queens outlier at 5Pointz finishing the rundown.

St. John’s University 101 Murray

Lower Manhattan (Tribeca)

101 Murray Street, New York, NY 10007

10 stories, 119 feet

Year: 1983

Use: Institutional

Replacement: Residential

The newest building on this list is also the most short-lived. 101 Murray Street, used for St. John’s University’s Manhattan campus, existed for only 32 years, between 1983 and 2015. Although the building was not distinguished enough to make it worthy of preservation, its unique look and massing made it stand out among anonymous office stacks common in the late 20th century. The 10-story concrete structure was designed by Haines Lundberg Waehler, who also worked on projects such as the nearby World Financial Center (now Brookfield Place) and One Pierrepont Plaza in Downtown Brooklyn. It rose from the trapezoidal plot as a Modernist ziggurat, with its acute angles softened with chamfered corners. Bands of green tinted windows encircled the building, balancing the stepped vertical climb with a decidedly horizontal rhythm. A sloped skylight ran several stories high above the east entrance. It faced the parking lot that occupied the rest of the block until 2006, when Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s 32-story 101 Warren Street tower commenced construction.

Despite its diminutive size, the building towered over its immediate neighborhood as recently as the early 2000s, when the new Goldman Sachs headquarters, 100 Chambers Street, 101 Warren, and the final phase of Battery Park City replaced nearby empty lots and parking zones.

In July 2013, the site with the 10-story building was sold to developers Steven Witkoff, Howard Lorber, and Fisher Brothers, for $223 million, one of the most expensive land sales in Downtown Manhattan’s history. St John’s has signed a 99-year lease for 71,000 square feet of space at Minskoff Equities’ new building at 51 Astor Place.

Demolition of 101 Murray began at the end of 2014. The building was torn down during the first half of 2015.

111 Murray Street , a 792-foot, glassy residential tower designed by Kohn Pedersen Fox, is slated to rise at the site, adding a slender presence among the bulkier towers on the surrounding blocks.

Despite new density, the residential tower will still have plenty of breathing room at ground level, standing adjacent to the eight-lane-wide West Street and the Battery Park City ballfields beyond. Though the new tower will put the old site to much better use, the old building had a certain degree of appeal and gave a sense of place to the area when it was an under-built periphery zone between the Financial District, TriBeCa, and Battery Park City.

———

Bancroft Building

Midtown South (NoMad)

3 West 29th Street, New York, NY 10001

10 stories

Year: 1896

Use: Religious, commercial (office)

Replacement: residential, public park

The next building is not only the oldest on the list, but also the most architecturally and historically significant. Built in 1896, the building’s existence spanned 119 years, occupying time in three centuries. Upon completion, it stood among the ranks of the tallest buildings in the city. The prominent architect of his time, Robert Henderson Robertson, created a robust facade of red brick and white stone, fusing Romanesque and Classical elements, inspired by a prominent church theme. Its 10 floors housed an array of architecture firms, publishing and advertising companies, the YMCA, and the Camera Club of New York. The latter, under its president Alfred Stieglitz, was one of the early organizations that, intentionally, elevated photography into an art form.

In the middle of the twentieth century, Marble Collegiate Church purchased the building. While most of its space remained as leased offices, the lower two floors were retrofitted with with a Sunday school, a chapel, and social rooms. The base was expanded outwards, with an amplified religious theme. In 2013, the church sold the building to HFZ Capital, which proceeded with demolition despite preservation efforts by the community. 8-16 West 30th Street, a 12-story pre-war commercial building directly north, is scheduled to bite the dust this year. The combined mid-block site could house the tallest building NoMad – a recently re-branded district north of Madison Square.

The 64-story, 800-foot-tall tower is designed by renowned architect Moshe Safdie. Its staggered residential clusters resemble a vertical descendant of the famous Habitat 67 complex in Montreal, built for the 1967 World’s Fair. While the tower will rise on 30th Street, the 19th century Romanesque Revival tower will be replaced by a park. While a green space and an elaborate building by a prominent architect are welcome additions to the neighborhood, the Bancroft Building was a prime candidate for preservation. At the very least, its facade should have been incorporated into the new project.

———

1205, 1225, and 1227 Broadway

Midtown South (Herald Square)

1205, 1215-1225 and 1227 Broadway, New York, NY 10001

2 stories (1205), 9 stories (1225), and 4 stories (1227); 90 feet (1225 Broadway, approx.)

Year: 1921 (1225 Broadway)

Use: Commercial (office, retail)

Replacement: Hotel

1205, 1225 and 1227 Broadway. Looking northwest from West 29th Street and Broadway. Left: August 2013 (image from Google). Right: January 2015

A few blocks northwest of Bancroft Building, three pre-war buildings have been cleared from a block long stretch of Broadway. Demolition commenced in 2014 and the site was cleared by mid-2015. Although not as distinguished as Bancroft, the trio was a decent group of commercial structured that were good representatives of its neighborhood. The three-story, low-slung 1205 and the tallest of the group, 1225, were unified with matching signage above their seedy yet vibrant strip of retail.

The replacement is also a good representative of the changes that are transforming Herald Square South. New York’s first Virgin Hotel will be yet another hotel addition to the neighborhood that is rapidly increasing its hospitality offerings.

———

Former Mercedes-Benz dealership at 520 West 41st Street

520 West 41st Street, New York NY 10036

Midtown (Far West Side)

3 stories

Year: post-WWII

Use: Commercial (car dealership)

Replacement: Residential, retail?

520 West 41st Street. Left: December 2014, looking northwest (image from Google). Right: looking east in August 2015

2015 was the year when the decade-long residential development along the West 42nd Street corridor finally met the accelerating construction in the Hudson Yards district, which is rising on the blocks to the south. As the 610-foot-tall, 600-unit 547 10th Avenue rises between West 40th and west 41st Streets, a car dealership has been cleared from the block to the west to make way for a much larger development. The sprawling Mercedes-Benz dealership occupied the entire block between West 40th and West 41st Streets, Eleventh Avenue, and Galvin Avenue, a one-block conduit that funneled traffic to the Lincoln Tunnel ramps on the block to the south.

The low-rise, sprawling dealership building occupied almost three quarters of the 93,000-square-foot block, with the rest of the site paved over for a parking lot. The massive building rose directly from the lot line and overpowered the surrounding landscape with its windowless walls clad in dark tile at the ground level and water-stained metal panels on the levels above. Although the constant bumper-to-bumper traffic at the tunnel approaches does not help, the hulking building ensured that the surrounding streets are some of the least pleasant in the borough, especially in combination with the Michael J. Quill Bus Depot one block west and equally offensive-looking low-rises to the north.

Despite everything, the building held a certain appeal. Its geometry consisted of assertive, interlocking shapes that broke down its bulk, and the St. Cyril and Methodius and St. Raphael Croatian Church-facing eastern façade was an angled wall of glass blocks, which caught the morning sunlight in an appealing manner. When it was in pristine condition at its prime, with large Mercedes ornaments on its walls and clad in unstained panels, the building must have looked like a sleek machine built for showcasing equally sleek automobiles.

In 2011, developer Larry Silverstein expressed interest in the site. The dealership has since relocated to the ground floor of the appropriately named Mercedes House, a luxury rental building shaped like a rising, stepped spiral and developed by Two Trees. Located between West 53rd and West 54th streets, the new dealership is much closer to the core of Midtown’s Automobile Row district. Silverstein paid $100 million for the 41st Street site, hoping to occupy it with one of the city’s largest buildings. The new tower was slated to rise 1,000 feet, with 300,000 square feet of retail and 1,400 apartments spread across 106 floors.

As of today, the site’s future is uncertain since Silverstein put it back on the market. Regardless, barring unforeseen circumstances, whatever ends up being built is bound to be a crucial connector between the 42nd Street corridor, Hell’s Kitchen, and the booming Hudson Yards district.

———

701 Seventh Avenue

701 Seventh Avenue, New York NY 10036

Midtown (Times Square)

10 floors, 128 feet

Year: 1909

Use: Commercial (office, retail, advertisement)

Replacement: Hotel

701-Seventh-Avenue-wmark-composite-small; 701 Seventh Avenue. Looking northeast. Left: December 2006 (topped with the Phantom of the Opera billboard). Right: December 2015

The turn-of-the-century office building stood on the northeast corner of the Times Square bowtie at the intersection of Seventh Avenue and West 47th Street. Although it was largely obscured by billboards in its later years, it was one of the last holdouts of the old Square, lasting 106 years. It was a part of the first wave of large-scale development, contemporaneous with distinguished neighbors such as One Times Square and the Hotel Astor. At the time of demolition, it was the second oldest remaining building at the Square. At the moment, only three pre-war buildings remain at the bowtie.

The Marriott Edition Hotel, which will feature one of the Square’s largest LED displays wrapped around its base, is slated as the replacement.

———

425 Park Avenue

425 Park Avenue, New York NY 10022

Midtown (Midtown North)

32 stories, 387 feet

Year: 1957

Use: Commercial (office)

Replacement: Commercial (office)

The tallest building in the rundown in the only one slated for partial, rather than full, demolition. A loophole in Midtown East zoning allows developers to maximize new square footage if they retain the lower quarter of the existing structure rather than demolishing it altogether. The building will be retrofitted into a 900-foot-tall office skyscraper designed by Norman Foster’s architecture team, standing catty-corner across from 432 Park Avenue. The building will feature floor-to-ceiling windows and will be the first new office tower on the avenue in decades.

The demolition that took place throughout 2015 was mostly interior, while the exterior was wrapped in black netting.

———

American Piano Company Building

29 West 57th Street, New York NY 10019

Midtown (Billionaire’s Row)

15 stories, 165 feet (approx.)

Year: 1925

Use: Commercial (office, retail)

Replacement: Residential, retail?

29 West 57th Street. Left: View of the crown pre-demolition (image from Wikimedia). Right: November 2015, looking northeast

29 West 57th Street and its neighbors to the west, are arguably the most architecturally distinguished buildings that Midtown lost over the course of the year. The slender tower was built by a piano manufacturer and featured golden caryatids at its pinnacle, with similarly gilded spandrels between the windows. The set of buildings is set to be replaced by a yet-undisclosed tower developed by SHVO, which is very likely to join the lofty ranks of the rapidly rising along the 57th Street corridor now known as Billionaire’s Row.

———

5 Pointz Aerosol Art Center

45-46 Davis Street, Long Island City, NY 11101

Long Island City, Queens

5 stories

Year: 1892 (2 story and 3 story portions), 1915 (5 story portion) (approx.)

Use: Cultural (art display)

Replacement: Residential, retail

5Pointz. Left: December 2013, looking north from Crane Street. Right: November 2015, looking northwest

For the last entry, we visit the other side of the East River opposite from the Billionaire’s Row, where another development boom demands its own sacrifices. The former Neptune Water Meter factory complex at 45-46 Davis Street in Long Island City is the oldest buildings on the list: built in 1892, the 2- and 3-story portion predates even the Bancroft Building by four years. However, it is the most significant structure of all not merely because of its age or architectural detail (both of which merit respect on their own terms), but because of the cultural that it took on since the early 1990s. While the Bancroft Building’s occupants helped elevate photography into a respected art form, 5 Pointz arguably did the same for the still-fresh art of graffiti and urban murals. Developer David Wolkoff allowed muralists to paint the exterior of the loft building, which became a dynamic canvas known as 5 Pointz. Despite being the only building on this list outside of bustling Manhattan, it is also the only one with true global fame, and visitors came to see it from near and far.

In November 2013, Wolkoff’s crews began whitewashing the art in preparation for impending demolition. According to the developer, who, in one interview, alleged that he “loved – not just liked – what the artists did with the building” and that the whitewashing process “brought tears to his eyes”, yet added that it would be easier to bear than tearing down each piece one by one. Whether the reader chooses to emphasize with Wolkoff or to question his integrity, his claim is understandable: why would a developer that hates graffiti allow his building to be tagged with murals for decades on end, unlike any other project in the city? It is similarly difficult to blame the building owner for passing up the opportunity to develop a huge, highly lucrative site in the middle of one of the city’s hottest neighborhoods. Of course, this does not make it any easier for us to watch the destruction of a truly unique art destination known all over the world. In a more ideal compromise, we would have seen the loft building re-purposed as the base for the new project, which is rather common even in Long Island City itself.

The new development, which goes by the address of 22-44 Jackson Avenue, will be one of the game-changing megaprojects that will take the scale of Long Island City development to new heights. Two towers, standing 48 and 41 stories, will house 1,116 rental apartments, as well as a large retail component at the base. The development will continue the graffiti tradition at the site by providing a 40-by-80-foot dedicated spray paint space above the garage, paintable walls around the 30,000-square-foot courtyard behind the complex, and open wall space on Davis Street. Furthermore, the complex will house 20 artists’ studios. “We’re happy to do it,” claims Wokloff, while critics dismiss the move as a concession to protesters. In either case, it remains to be seen whether the developer can replicate the success of the original by creating a new epicenter for graffiti art, or if the idea would fade away as a forced gimmick. Much like the walls of the old 5 Pointz, the city’s physical and cultural landscape is a shifting and often unpredictable canvas, and there is no knowing what the future really has in store for us.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

You left out PS31 in the Bronx.

I’m shocked to see some of these grand old buildings go. They have been sacrificed for commerce and greed. The Bancroft and the Piano building should have been saved.

These ‘developers’ are vandals.