As befitting one of the planet’s key engines of economic and cultural motion, New York City exists in a state of constant change. This is particularly true for the city’s older, centrally located neighborhoods, such as TriBeCa. Over the past two centuries, its western portion along West Street has been repeatedly transformed beyond recognition, particularly by the 1960s urban renewal program that completely cleared dozens of formerly-vibrant blocks. But even there, a 32-year building life span is short by any measure.

Designed by architect Haines Lundberg Waehler, 101 Murray Street rose at the corner of Murray and West streets in 1983. Despite its relatively low, 10-story profile, the trapezoid-shaped ziggurat towered prominently over the empty blocks paved over with parking lots and the newly created ground on the other side of the wide West Street, awaiting the eventual development of Battery Park City. As the city’s largest produce market turned no man’s land has transformed into one of the city’s most exclusive residential addresses, the site would become home to the latest herald of the luxury high-rise movement. The building was dismantled by mid-2015 after the site was sold for one of the highest prices in Lower Manhattan history. It is being replaced by a soaring, 857-foot-tall skyscraper designed by Kohn Pedersen Fox and Goldstein, Hill & West. The curving glass tower will be known as 111 Murray Street.

Since its earliest days, the city’s growth was driven by maritime commerce. Workers and merchants hustled along the narrow streets at Manhattan’s southern tip. They set up shops, offices, and warehouses close to the dock piers that lined the three sides of the peninsula, ready to receive goods from all over the world. Shortly after its first market opened in 1812, Washington Street, one block east of the Hudson River, became home to one of the nation’s busiest hubs of produce trade.

Washington Market, 1823. Looking northwest. Credit: New York Public Library via Medium

Washington Market, looking west. 1853. Credit: Project for Public Spaces, Nov. 25, 2012

Washington Market, 1859. Looking northwest. Credit: New York Public Library via Medium

Washington Market stretched along the western edge of the neighborhood that was known as the Lower West Side, before the word TriBeCa existed. While an 1872 New York Times article described the market as filthy and cramped, it praised its wares as “luxuries of an entire continent, and the fruits of the islands in the tropic seas.” The market’s main building stood at the site presently occupied by One World Trade Center.

Washington Market, looking west. 1916. Credit: Project for Public Spaces, Nov. 25, 2012

Washington Market, illustrartion. Credit: Project for Public Spaces, Nov. 25, 2012

West Street, looking north, June 9, 1918. New York Public Library Digital Collections. Image ID 724596F

The Washington Market building. Around 1925. Ewing Galloway, via the New York Public Library Digital Collections. Image ID 724100F

The Washington Market building. October 14,1927. Percy Loomis Sperr, via the New York Public Library Digital Collections. Image ID 724593F

By the turn of the 20th century, commercial buildings in Lower Manhattan stretched their spires higher than mankind had ever seen. While the office core around Broadway challenged the clouds for supremacy over the sky, its fringes still teemed with maritime and market life. On the eastern side of the wide West Street, the block between Park Place to the south and Murray Street to the north, where 101 Murray would eventually rise, was home to a row of five-story commercial structures. The buildings were typical for the neighborhood, with wide metal canopies protecting sidewalk traders from the elements.

Future site of 101 Murray Street. August 4, 1930. Percy Loomis Sperr, via the New York Public Library Digital Collections. Image ID 724603F

Washington Market district, prior to the construction of the West Street expressway. Looking north from the Barclay-Vesey Building. August 6, 1930. Percy Loomis Sperr, via the New York Public Library Digital Collections. Image ID 724597F

Pedestrian walkway across West Street along Barclay Street. August 2, 1930. Percy Loomis Sperr, via the New York Public Library Digital Collections. Image ID 724598F

Up and down West Street, particularly in the commercial enclaves north of Washington Market, crowding and traffic congestion reached dangerous levels.

Washington Market congestion. Early 20th century. Credit: Forgotten New York, September 2000

Construction of the elevated West Side (Miller) Highway began north of Canal Street in 1929, spearheaded by master builder Robert Moses. By the time the highway portion running past Washington Market opened on November 29, 1948, the district, which held strategic commercial importance for nearly a century and a half, entered a state of precipitous decline. As the wide street was overshadowed by the elevated expressway, so was the traditional, break-bulk cargo transport system overtaken by the post-war advent of container shipping. The Manhattan piers became increasingly incapable of servicing container ships. As ships grew not only in size, but also in numbers, the industry left Manhattan’s obsolete piers for newer, more spacious facilities in Brooklyn and New Jersey across the river. The second strike came in the same year, when the Interstate Commerce Commission allowed fees for shipping between New Jersey and Manhattan, increasing the costs of transporting goods to and from the city. The dock workers were not the only ones leaving the neighborhood. The post-war advent of suburbia, enabled by expressways such as the one that just opened on West Street, eased the automobile commute to and from the city and encouraged city residents to flee to greener pastures across the river.

The final blow came from city government, which aimed to streamline food distribution. In the middle of the twentieth century, Washington Market was still the city’s hub for produce and dairy. On the other side of Lower Manhattan, the South Street Seaport was the go-to destination for fishmongers. The Gansevoort Street area rounded off the food trifecta with the Meatpacking District. In 1962, city planners moved a number of services from all three to Hunts Point in the Bronx. The consolidated district was more adequate than the crumbling facilities and decaying infrastructure of the old districts. In addition, Hunts Point was better-served by Robert Moses’s network of bridges and expressways. Despite the crippling effects the new roads had on the neighborhoods that they sliced across, they were efficient channels for moving traffic. The same could not be said about the West Side Highway. This earlier, failed experiment by Moses was obsolete soon after construction. Its narrow lanes and sharp curves, particularly its entrance ramps, were ill-suited for general traffic and altogether prohibitive for trucks.

The neighborhood was known as Hell’s Hundred Acres in the first half of the 19th century, when it was home to the city’s vice district. The name took on a new meaning after the post-war commercial exodus. The maritime fringes of Lower Manhattan were turning increasingly desolate. The area from Broadway to the Hudson River, and from Reade Street in the south to 8th street in the north, became a no man’s land of crumbling industry and illicit activity. The neighborhood’s redemption lay under the sunlit, high-ceiling industrial lofts that provided the creative freedom needed to place TriBeCa at the epicenter of the city’s art explosion. Its shockwaves spread deep into the adjoining districts and eventually across both the East and Hudson Rivers, where its aftershocks are felt to this day in Bushwick and Jersey City.

While it is tempting to romanticize the appealing sides of yesteryear New York, it is understandable that the city was not happy with the crime-ridden, post-industrial relics. But even with this consideration, it is difficult to justify the means used to improve (or “improve”) the neighborhood. At that time, city planners believed that the path to urban salvation was to be paved with the ruins of the pre-war city, replaced with swaths of Modernist housing projects, minimalist office slabs, and windswept concrete plazas.

Washington Market, 1956, occupying the present-day site Of One World Trade Center. Looking northwest. Credit: New York Public Library via Medium

Credit: Project for Public Spaces

Credit: Project for Public Spaces

While the Fulton Fish Market and the Meatpacking District did not begin to feel true real estate pressure until the start of the new millennium, Washington Market was wiped clean in one fell swoop. In 1966, demolition was slated for an astounding sixty acres of Lower Manhattan, including numerous nineteenth century buildings. Those that did not want to leave their premises voluntarily were forced out via eminent domain. While destruction struck many points of the neighborhoods south of Canal Street, the most glaring change took place along the Hudson River. A nearly mile-long, two-block wide stretch east of West Street, from Albany Street to the south to Hubert Street to the north, was slated for urban renewal.

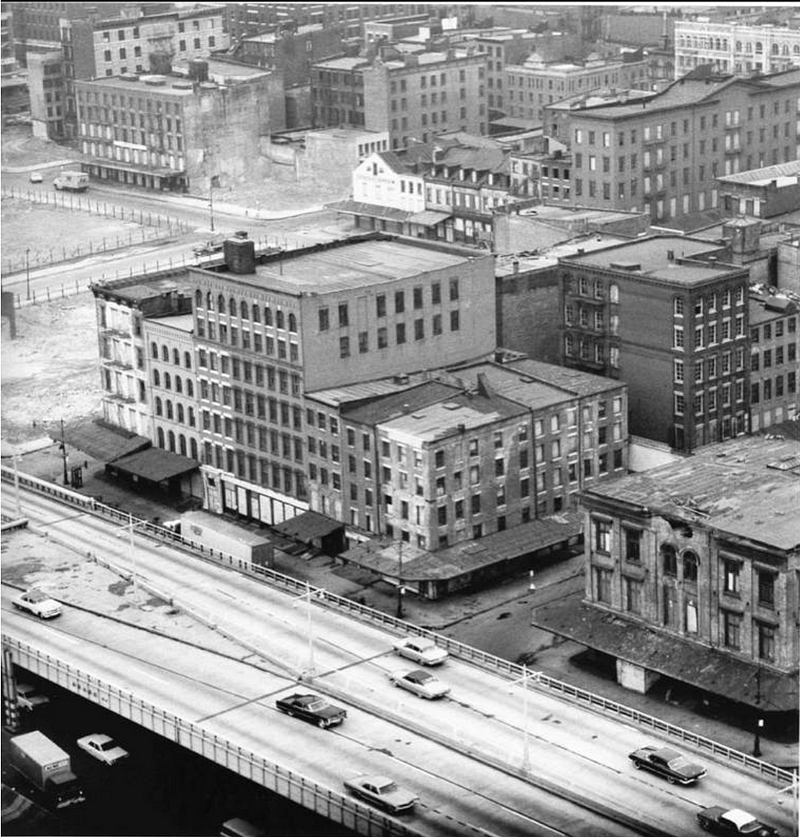

Demolition begins. Washington Market district around Duane Street, three blocks north of the site of 101 Murray Street. The West Side Highway is in the foreground. Around 1965. Credit: Tribeca Trust via Medium

Danny Lyon, a 25-year-old living on Beekman and William streets on the other side of Downtown, scrambled to document the disappearing cityscape, fascinated by the monumental wave of change that was about to wash over this part of the city. He published his record in “The Destruction of Lower Manhattan,” which remains one of the only sources documenting the numerous buildings wrecked at and around Washington Market.

Demolition of Radio Row at the future World Trade Center site. The West Side Highway and Hudson River piers are in the background. 1960’s. Via archimaps.tumblr.com. Photographer unknown.

More than thirty city blocks were reduced to rubble. A handful of historic townhomes were preserved on Harrison Street. Aside from them, only two significant buildings remained standing – the 490-foot-high, 32-story Barclay-Vesey building, an Art Deco masterpiece dating back to 1925, and the 10-story office stack across the street at 125 Barclay, built in 1932. The 16 acres to the south made way for the World Trade Center, which replaced Radio Row.

May 28, 1973. The World Trade Center was nearing completion and the Battery Park City landfill was underway, while acres of cleared land to the north still sat empty. 101 Murray would eventually rise at the lot behind Barclay-Vesey and 125 Barclay, seen to the left of the North Tower. Image hosted at domusweb.it. Photographer unknown.

To the north, not only the once-bustling Washington Market was removed from existence, but Washington Street itself was dismantled over the course of its almost mile-long run between Albany and Hubert streets. The apocalyptic landscape of crumbling commerce was replaced with empty, post-apocalyptic streets slicing across barren dirt lots. As years went on, a number of cross-streets were de-mapped, as well. While such sights are still common across poverty-stricken, post-industrial cities of the Rust Belt, it is odd to connect this look with TriBeCa, now one of the world’s most expensive neighborhoods, from just one generation ago.

Future site of Independence Plaza. 1969. Melissa Schook, Collection Landfield family, via Medium

The city was slower to rebuild than to destroy. The first buildings built at the site of the former market were the 39-story brick residential triplets known as Independence Plaza, completed in 1974.

Independence Plaza rising in 1973. Looking south. Credit: Wil Blanche via National Archives, hosted at photographyinamerica.wordpress.com

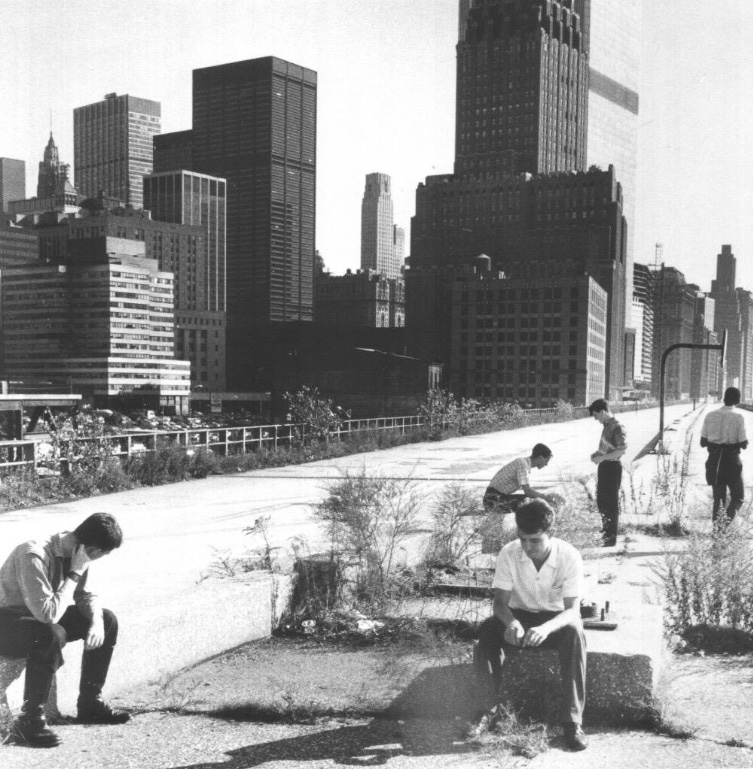

The towers stood in solitude for almost a decade, during a time when the crime-ridden city’s future looked rather bleak. The southern portion of the superblock was redeveloped as Washington Market Park at the start of the 1980s, thanks to community activists that prevented the space from becoming a parking lot. In the meantime, the derelict, elevated West Side Highway, saw its last vehicular traffic in 1973, when the northbound lanes between Little West 12th Street and Gansevoort Street collapsed under the weight of a dump truck carrying asphalt for ongoing expressway repairs, taking another car down with it. Although neither driver was seriously injured, the portion south of 18th Street never reopened to traffic again. The elevated viaduct became something of an early, unauthorized High Line prototype for those brave enough to trespass upon its derelict surface, until it was dismantled around 1981-1982.

Members of the post-punk band A Certain Ratio atop the abandoned expressway. Circa 1980-1981. In a couple of years, the viaduct would be gone and 101 Murray would stand at the center of the photo. Unknown photographer

In the meanwhile, the block-long segments of Park Place and Murray Street to the south were de-mapped. Murray was re-routed at an angle in order to connect to the new street grid of Battery Park City, which would rise on the landfill that replaced the old piers. Combined with the prior closure of Washington Street, the new angled arrangement transformed what used to be six blocks into two trapezoidal superblocks.

Higher education institutions were significant contributors to Downtown’s urban renewal. A number of buildings demolished in the 1960s near the Brooklyn Bridge were replaced by the expansion of Pace University. By the early 1980s, the towers of Independence Plaza was joined by the low-slung slab of the Borough of Manhattan Community College at 199 Chambers Street, which stretches along West Street for five blocks. The new facility complemented BMCC’s Fiterman Hall, which has stood four blocks south at 70 Murray Street since 1959. St. John’s University joined the fray at the start of the 1980s, when it drew up plans for development at a 39,401-square-foot trapezoidal lot at the intersection of Murray and West streets.

By 1983, the university opened their 145,000-square-foot facility at 101 Murray Street. After completing the project, its architect, Haines Lundberg Waehler, went on to design the nearby World Financial Center, together with the architecture firm of César Pelli. 101 Murray Street, a 118-foot-high Modernist ziggurat, rose in a series of setbacks towards the 10-story pinnacle at the center. Bands of light beige concrete alternated with strips of green tinted windows, bestowing the pyramidal shape with a decidedly horizontal rhythm. The irregular shape of the lot ensured that there was not a single right angle in the entire composition. Though chamfers softened the building corners, its acute-angled mass made for a dramatic presence when viewed from the intersection of West and Murray streets. The stepped climb of the east façade was bisected with a sloped skylight, which rose above the lobby.

The Empire State Building lost its singular dominance over the world’s most famous skyline by the early 1970s, when twin usurpers rose over the Downtown skyline as the world’s tallest buildings. The Twin Towers of the World Trade Center became instant icons for the city and for the country as a whole, rooting themselves deep within the public psyche. But the inward-oriented complex did little to energize the surrounding neighborhood, and the blocks to the north remained a veritable urban wasteland. Despite sitting just two blocks north of some of the tallest buildings on the planet, the blocks around 101 Murray were barren enough that its stout, 10-story profile reigned over the streetscape. Its north blank wall towered over the 90,565-square-foot parking lot that took up the remainder of the lot. The block across Warren Street to the north, fronting Washington Market Park and the BMCC campus, sat empty until the late 1980s, when P.S. 234 rose on its eastern half. To the west, 101 Murray faced the 10-lane wide West Street. The barren expanse of Battery Park City on the other side was not fully developed until decades later.

By 1985, the site across the street and to the east was redeveloped with the curved-glass, 325-foot-tall office block at 101 Barclay Street, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Otherwise, the surrounding neighborhood remained largely unchanged until the turn of the millennium. The year 2001 has the somber distinction of marking the deadliest terrorist attack on American soil, when the collapse of the World Trade Center killed thousands and coated the area with a thick layer toxic white dust. As local parking lots were used for staging by first responders, skeptics predicted doom-and-gloom for the future of high-rise construction. In spite of their dark predictions, the city rebounded stronger than ever, with its latest skyscraper influx rising as a symbol of its latent potency.

Though the days of Hell’s Hundred Acres still lingered in recent memory, TriBeCa had completed its transformation into one of the most exclusive addresses on Earth. In 2005, the block to the north welcomed a 29-story luxury residence at 200 Chambers Street. One year later, the parking lot next to the university building became a construction site for the 35-story, mixed use residential and retail complex at 101 Warren Street. Its blank wall now towered above the 101 Austrian pine trees that sit atop its neighbor’s podium, which hugged the university building on two sides. In 2009, the $2.1 billion, curved glass slab of the new Goldman Sachs Headquarters rose catty-corner from 101 Murray, on the opposite side of the West Street intersection. The remainder of Battery Park City to the north completed its development in the coming years. To the south, the open wound left in the skyline by the absence of the Twin Towers was filled by the first two towers of the new World Trade Center. The former neighborhood pioneer at 101 Murray became an underbuilt property in the midst of a hot real estate market, surrounded by a vibrant, round-the-clock neighborhood and hemmed in by larger neighbors on nearly all sides.

In 2013, St. John’s University left the TriBeCa building after signing a 99-year lease for 71,000 square feet within the new building at 51 Astor Place, in the midst of the academia neighborhood dominated by the New York University and the Cooper Union. In July of that year, 101 Murray was sold to developers Steven Witkoff, Howard Lorber, and Fisher Brothers for $223 million, in one of the most expensive property sales in Lower Manhattan history. Demolition of the 32-year-old building began at the end of 2014 and wrapped up by mid-2015.

August 2015. Photo by ILNY on Flickr via 6sqft.

As seen from the Goldman Sachs Headquarters. The green roof atop the 101 Warren podium is seen in the background. October 2015. Photo by Laura via Tribeca Citizen.

The city skyline is akin to a stock chart: the higher the peak, the more money is involved. The project proposed for the site will reflect this reality. “Modernism lives in Tribeca,” proclaims the website of 111 Murray Street, developed by the Witkoff Group, Fisher Brothers, and New Valley, and designed by Kohn Pedersen Fox. Goldstein, Hill & West Architects is the architect of record, while the interiors are designed by Rockwell Group and MR Architecture + Décor. The footprint of the slender tower would be half the size of its predecessor, with the rest of the space articulated as a public plaza designed by Edmund Hollander Design. Its slender glass form would rise more than seven times as high as the trapezoidal ziggurat it replaces, packing 157 luxury residences onto 480,400 square feet. The 58-story tower would espouse a graceful silhouette, growing slightly wider as it rises to its 857-foot-high pinnacle. Its all-glass facade, curved corners, and slanted crown bear a resemblance to 50 West Street, the 784-foot-high luxury residential building developed by Time Equities and designed by Helmut Jahn, which is nearing completion half a mile south. When viewed from across the Hudson River, the pair would bookend the resurgent Downtown skyline, anchored by the 1,776-foot-tall pinnacle of One World Trade Center in between.

Credit: Kohn Pedersen Fox / Goldstein, Hill & West Architects via Tribeca Citizen

Credit: Kohn Pedersen Fox / Goldstein, Hill & West Architects

Credit: Kohn Pedersen Fox / Goldstein, Hill & West Architects

Credit: Kohn Pedersen Fox / Goldstein, Hill & West Architects

As of mid-June, the tower’s basement levels are underway.

Looking east from West Street. June 2016. Photo by mchlanglo793 on Yimby Forums.

The streets of New York are a fluid canvas shaped by fishmongers and luxury developers alike. Over the course of the past two centuries, the blocks along West Street saw some of the city’s most turbulent change. 101 Murray had graced the site of the former Washington Market for only 32 years, and the Postmodern ziggurat was not distinguished enough to make a lasting impression upon the city as a whole. However, the building deserves its place in the city’s architectural memory thanks to its low-key but robust design. Though the angled stack of concrete and glass bands, unlike any other the city has ever seen, is gone, we look forward to seeing the sleek skyscraper silhouette standing in its place.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews