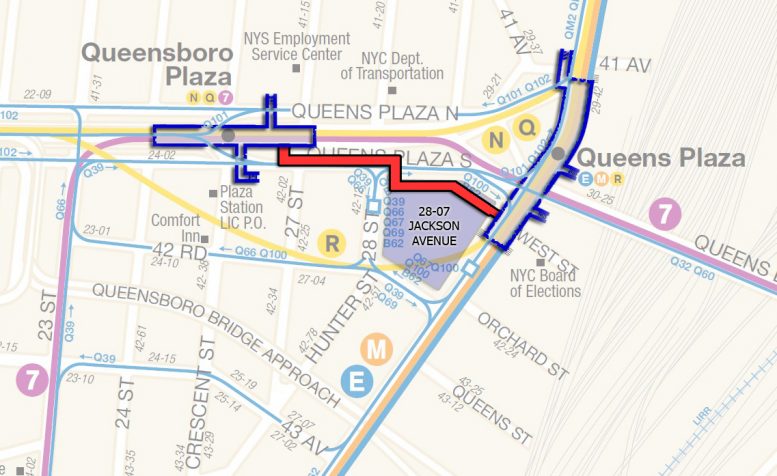

Six of the seven subway lines that connect Queens to Manhattan converge at the foot of the Queensboro Bridge, where Queens Plaza meets Queens Boulevard, Northern Boulevard, and Jackson Avenue. There, the elevated Queensboro Plaza station handles the N, Q, and 7 trains, while the E, M, and R serve the underground Queens Plaza stop. The two stations face increasing pressure from steady growth in both Long Island City and the borough as a whole, as well as the impending overflow of Brooklyn commuters displaced by the L train shutdown. The need for a transfer connection between them has become more pressing than ever.

Given the MTA’s cash-strapped budget, private involvement is more likely. Luckily, Tishman Speyer and H&R REIT are planning a million-square-foot office and retail complex at 28-07 Jackson Avenue, designed by MdeAS Architects, directly between the two stations. The developers should connect the stations through the underground level within the complex, relieving commuter pressure while allowing the builders to create more floor space through city incentives.

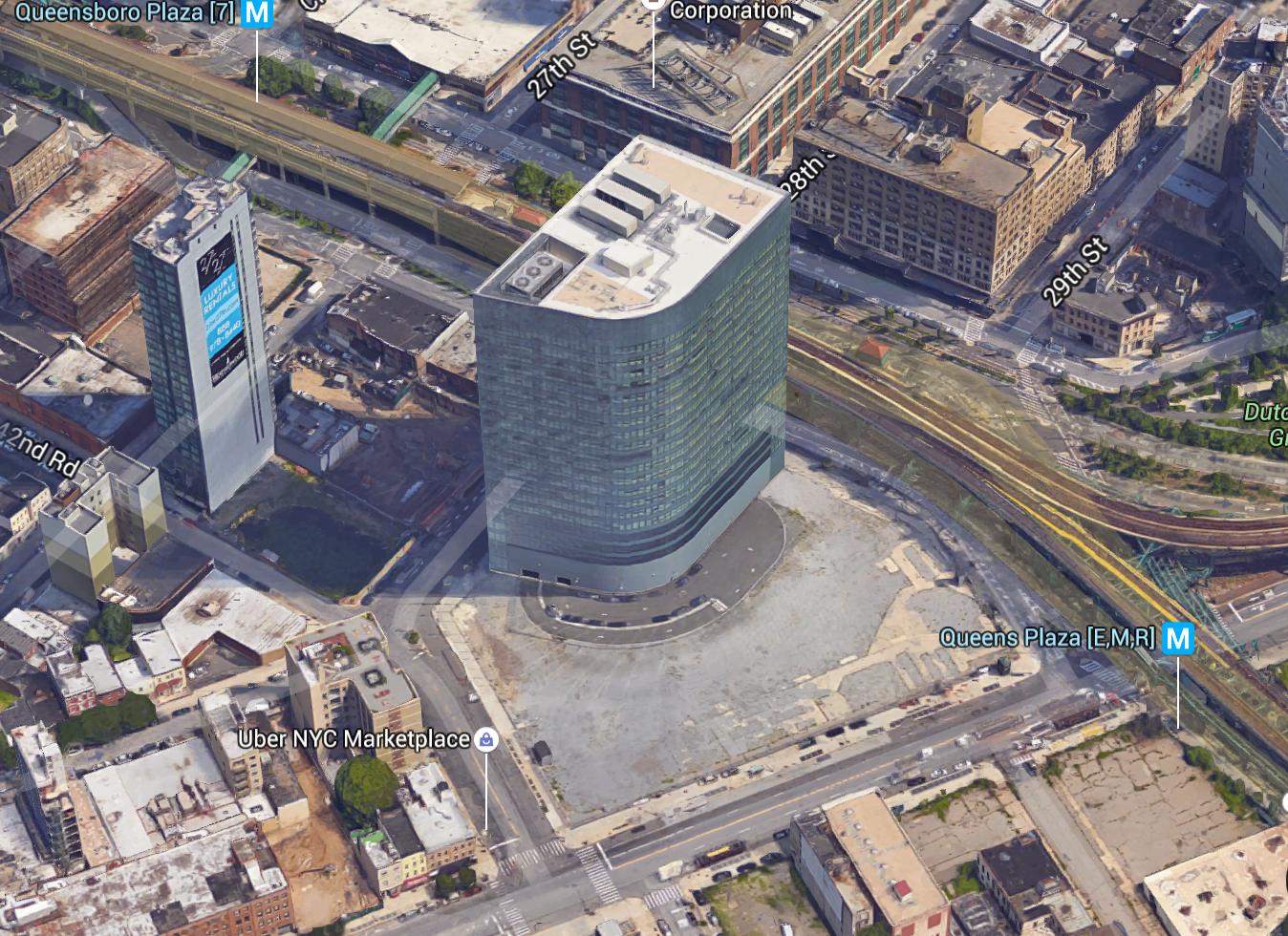

Two Gotham Center and the site of 28-07 Jackson Avenue. Queensboro Plaza is at the top left and Queens Plaza is at the bottom right. Image via Google Maps.

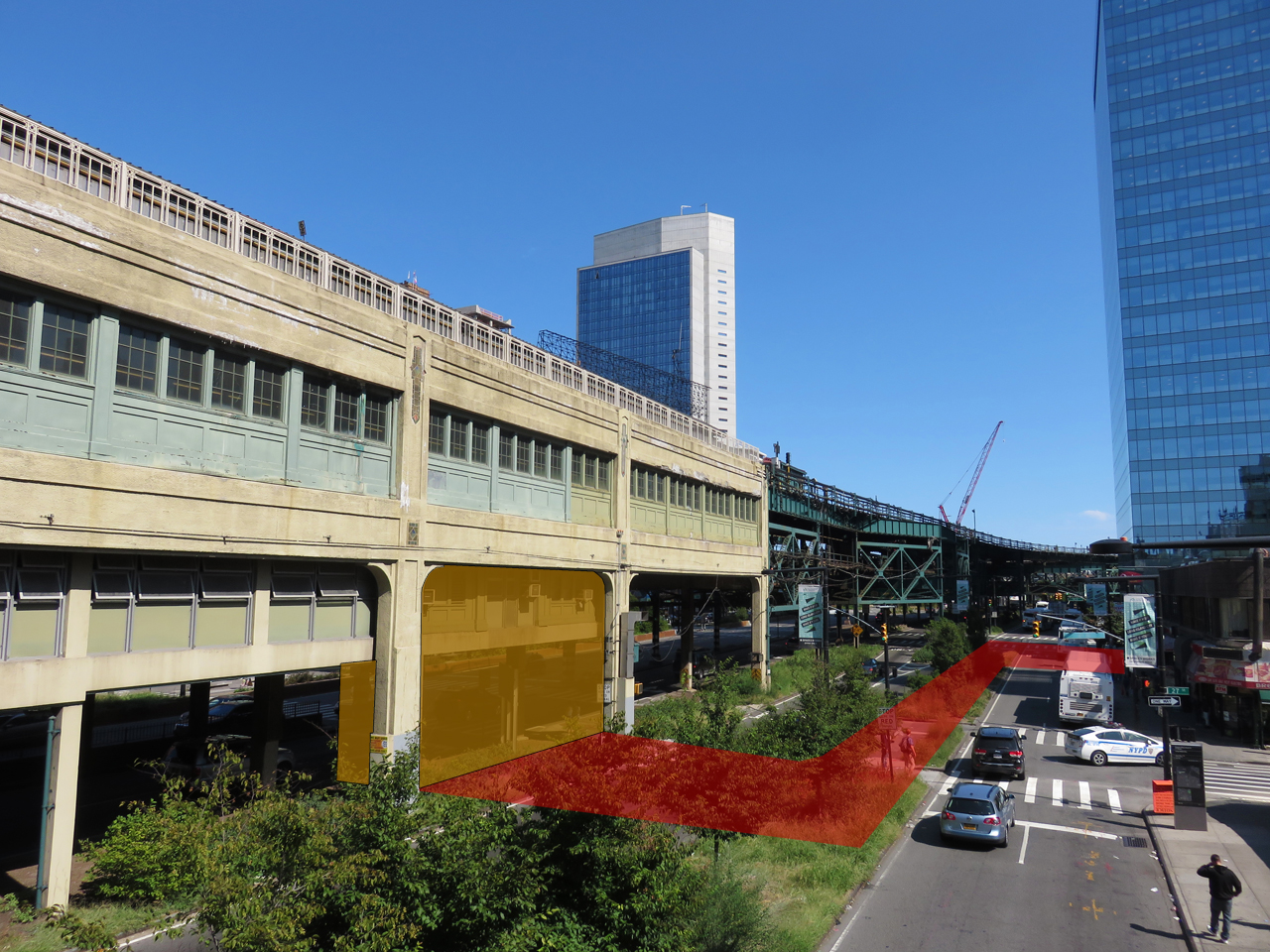

The underground passage (red) would run from Two Gotham Center, right, to the median under the Queensboro Plaza platform, to which it would connect via stairs and elevator (yellow)

Queensboro Plaza, part of the BMT/IRT system, opened in 1915, six years after the completion of the Queensboro Bridge. The 1933 Queens Plaza station was built by the competing IND operator.

Even after the consolidation of the subway, the city was in no hurry to connect the stations. On the contrary, the MTA shuttered several cross-station connectors at other locations in the 1970s after crime became a major issue and ridership dropped precipitously. At that time, the Queens Plaza neighborhood was characterized by crumbling warehouses, desolate parking lots, and street crime.

The city’s ongoing renaissance has made both the streets and the platforms much safer. Over the past twenty-five years, almost 400,000 new residents arrived in Queens, with around 108,000 between just 2010 and 2015, pushing the borough past the 2.3 million mark. Long Island City alone has added 11,000 dwellings over the past decade, with 22,000 more in the pipeline. Half of these lie within a few blocks of Queens Plaza, in a district spanning just 0.17 square miles. In addition, Long Island City trains and stations, particularly the G and 7 trains at Court Square, will soon be flooded with hordes of Manhattan-bound Brooklynites displaced by the impending L train shutdown.

The G train stops a few blocks southwest at the Court Square station. The transit complex, which also services the E, M, and 7 trains, was originally built as three independent stations. When Citigroup built its 50-story tower, now known as One Court Square, in 1990, the banking giant introduced a 360-foot-long passageway between the E, M, and G trains as part of a suite of community benefits. The project provided much-needed pedestrian activity to the neighborhood, boosted the customer base for local businesses, and introduced retail within the building base. According to the New York Times, City Council Member Walter L. McCaffrey called the project “a textbook case of what went right.”

In exchange for its contributions, the builder received a floor-to-area ratio (FAR) bonus of 13.0, adding a whopping 1,068,093 square feet of office space. The 658-foot-tall building became the city’s tallest outside of Manhattan, and, according to former Community Board 2 chair Joseph Conley, “put Long Island City on the map.”

In 2011 , a link with two escalators, three elevators, and a stairway connected the underground station to the Court House Square station of the elevated 7 train. Like the 1990 connector, this intervention was also sponsored, for the most part, by Citigroup, which built the 15-story Court Square Two office building in 2007, across the street from the original tower. It netted the same FAR bonus of 13.0, which translated into additional 533,273 square feet of buildable office space.

The Court Square platform of the 7 train, with One Court Square on the right and Court Square Two on the left. The Hayden and Watermark Court Square, both under construction, stand in the middle.

Thanks to these successful public-private partnerships, the Court Square station has become a transit hub ready to serve thousands of displaced L train commuters. Station capacity would further increase once the hotel planned for 24-09 Jackson Avenue, across the street from One Court Square, introduces further station improvements, in exchange for a similar bonus of 13.0 FAR. Still, the severe pressure expected at the junction calls for added relief measures elsewhere.

The Court Square subway complex. Each of the three developments shown in red received a 13.0 FAR bonus for introducing subway connectors and improvements. Image based on illustration published by the NYC Department of City Planning.

In 2011, Tishman Speyer completed the 22-story Two Gotham Center at the intersection of Queens Plaza South and 27th Street, halfway between the Queens Plaza and Queensboro Plaza stations, and sold the property to Canadian-based H&R Real Estate Investment Trust (H&R REIT) for $415.5 million.

The sweeping curve of its light-green facade was scheduled to face two more office towers, which have been on hold for the past five years even as other new buildings continue to rise all around.

The project sprang back to life around June. Renderings released in July and September showed the new proposal, developed by Tishman Speyer and H&R REIT, consisting of two 23-story towers perched upon a shared, four-story podium.

28-10 Jackson Avenue at left — 28-07 Jackson Avenue at right

28-10 Jackson Avenue at left — 28-07 Jackson Avenue at right

Building permits list 900,509 square feet as commercial, with the 27,569 square feet devoted to manufacturing likely to attract tech start-ups. A 250-car garage accounts for most of the remaining space within the 1,146,546-square-foot complex. The project would rise across from the 1,900-unit residential complex at 28-10 Jackson Avenue, developed by the same team, where three towers ranging between 43 and 53 stories are currently under construction.

The 13,807 square feet of retail at 28-10 Jackson would work in tandem with the 43,000 square feet retail component proposed for the podium of 28-07 Jackson, creating a shopping corridor in a neighborhood in need of shopping and dining options. A subway passage could traverse the lower level of the podium, which would sit directly adjacent to to the underground mezzanine of Queens Plaza.

The west end of the complex sits just 330 feet away from the elevated platform of Queensboro Plaza. If measuring from the corner of the H&R REIT-owned Two Gotham Center, which the developer website describes as “on the doorstep of Long Island City’s most important transportation hub,” the distance drops to 210 feet to the platform, or 430 feet to the nearest station entrance. From that point the passage would continue as a tunnel under Queens Plaza South, spanning one block, or around 250 feet. At 28th Street it would feed directly into the elevated station mezzanine via a stair/escalator/elevator bank, placed within the median underneath the elevated structure.

Until such a passage is constructed, a commuter transferring from Queens Plaza to Queensboro Plaza would have to ride one stop via the E or the M to Court Square, make a 1,000-plus-foot-long underground hike to the elevated 7, and then ride one stop in opposite direction. Alternatively they may choose to exit the station, cross two intersections, and then re-enter the system with an extra fare.

Queensboro Plaza (in the distance), as seen along Queens Plaza South from the site of 28-07 Jackson Avenue (fence on the left)

Upon its 2011 opening, the MTA estimated that the connector between the underground Court Square and the elevated 7 train would serve 20,000 riders per weekday. This gives an indication of what could be expected at Queens Plaza. Though transfer conditions at the two hubs differ, the introduction of a Queens Plaza connector would guarantee some relief to Court Square, where congestion may reach dangerous levels once the L train shuts down. Every additional transfer node reduces crowding at other points.

Even the station name would most likely be shortened in tandem with the shorter commute. MTA aims to unify all connected platforms under the same moniker whenever possible. Case in point: the three stations comprising the present-day Court Square-23rd St complex were once known as 23rd Street–Ely Avenue (E and M trains–Queens Boulevard Line), Long Island City–Court Square (G train–Crosstown Line), and 45th Road–Court House Square (7 train–Flushing Line). The “23rd St” portion differentiates the Ely Avenue platforms as lacking elevator access. The most significant instance of station name unification took place when Fulton Center consolidated several Lower Manhattan stations into a single complex in 2014.

Each of the city’s iconic commercial complexes, such as the World Trade Center, the Time Warner Center, and Rockefeller Center, features direct subway connection. 28-07 Jackson Avenue has all the right ingredients for becoming a neighborhood anchor: a central location, dense urban surroundings, a shopping center, and a large amount of office space. Inclusion of the subway connector would cement its position as a true hub, further reinforced by the half-dozen bus lines that make the streets around the 28-07 Jackson block into a veritable open-air bus terminal.

The connector from the underground Court Square-23rd St to the elevated 7 train, built five years ago, cost $47.6 million. The government contributed $13.9 million while Citigroup paid for the rest. The extra length of the Queens Plaza connector would come with a higher price tag. However, city incentives provided to developers in exchange for transit improvements would almost certainly recoup even a $100 million investment within a few years.

Each of the two Court Square towers discussed earlier gained a floor-to-area ratio bonus of 13.0. The proposal at 28-07 Jackson currently clocks in at 7.66. If boosted by 13 points, the FAR would almost triple, allowing for a mammoth, three-million-square-foot office complex, significant even by Manhattan standards. Even a much lesser FAR bonus would greatly increase the size of the project.

According to the Wall Street Journal, Long Island City’s office space rents average $38 per square foot. 28-07 Jackson Avenue would likely command higher prices due to its location and proposed Class A classification. Even at the $38 dollar average, the roughly two-million-square foot space boost would net $76 million in extra revenue per year. At $50 per square foot, the bonus footage would pay for a $100 million passageway within a year. Even if Tishman Speyer and H&R REIT were rewarded with only one-quarter of the bonus that their Court Square counterparts received, the relatively modest 500,000 extra square feet would recoup the expense in five to six years.

Leasing the extra space should not be a problem. Already, 550,000 square feet have been pre-leased by Macy’s Inc. and 250,000 square feet pre-leased by the shared workspace provider WeWork. “We pre-leased 800,000 square feet, which was extraordinary, and we weren’t expecting that,” chief executive Rob Speyer told the Journal. Such demand is unsurprising, as Queens Plaza sits only one station away from Midtown Manhattan while Long Island City rents are only half of Manhattan’s asking average of $73. At the moment, Long Island City’s 13 million square feet of offices list a vacancy rate of at 7.7 percent, 1.1 percentage points lower than in Manhattan, with Class A office space vacancy as low as 6.4 percent.

Some may find it odd to advocate for extra density as a reward for a congestion-relieving passage. However, not only are such bonuses standard for transit improvement, but the connector’s congestion-relieving function would almost certainly outweigh any extra pressure it may add.

Last but not least, this connection would finally make the Queensboro Plaza platform accessible via the elevator, opening it for use by the disabled and those with limited mobility.

In summary, the neighborhood, faced with combined pressures of commuter growth and the L train shutdown, is in dire need of public transit upgrades. A direct connection between Queens Plaza and Queensboro Plaza could be a worthwhile upgrade, if Tishman Speyer and H&R REIT can work together with the city and the MTA. The first construction equipment has arrived at the site earlier this month. The time to act is now, while the project is still on the drawing boards.

Future site of 28-07 Jackson Avenue, with Queens Plaza station elevator and stairs in the foreground. Note the construction equipment on the left.

Subscribe to the YIMBY newsletter for weekly updates on New York’s top projects

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

Tall and tall I call development in the city, it is possible to see construction shows the new structure always.

Even without the added hordes of riders from the upcoming L trai shutdown, the Number 7 connection to the G/E/M trains is ALREADY dangerous at rush hours. Coming up the escalator one slams into a crowd trying to walk up the stairs to the Queens bound 7 train. It’s a recipe for disaster if there no room to get off the escalator and you’re pushed back onto the people already on the escalator who obviously have no where to go. Any nearby transfer points such as the article descibes would help alleviate this dangerous overcrowding at nearby Cort Square.

Thats “Court Square” and l TRAIN.shutdown

Western Queens subway stations and trains almost maxed out as it is. No one cares about infrastructure anymore. When all these high rises are fully occupied the subway stations and trains will be pushed beyond safe loading conditions.

For years, I used my unlimited MetroCard to go outside from the G train to the elevated 7 train, and unlimited MetroCard users can still do that if they want to avoid crowds. The new connector is great, but the old connection for those of us who can afford unlimited MetroCards was okay, unless the weather outside was horribly rainy or snowy.

This is why when the (L) shuts down in two years, the MTA needs to look at extending the (G) (M) and (R) at all times to 179th Street. That would allow the (G) to stop at Queens Plaza and allow people who need the Broadway Line to do a more simple transfer there. It’s also why I would be adding OOS transfers between the (G) at Fulton Street and the 2/3/4/5/B/D/N/Q/R at Atlantic Avenue-Barclays Center in Brooklyn, with the MTA encouraging as many people as possible to use that route if they have to transfer from the (L) at Lorimer.

The OOS transfer is a good idea, but there is not enough track capacity at Queens Plaza to run the G past Court Square.

Could this connection be designed and completed in time for the L train shutdown? Or is a makeshift, fenced-in connection at grade (ground/street) level between the Queens Plaza and Queensboro Plaza Stations the plan until the underground connecting tunnel could be completed at a future date? Also, would it be possible to create a special district/zone so that development within the area could finance the new transit transfer/hub if the developers balk at the plan or propose insufficient funding to allow for ample escalators/elevators for the amount of people who will be using the stations as LIC becomes further developed with high-rise buildings? For example, should Tishman Speyer and H&R REIT be solely responsible for the private sector’s contribution to fund this connection/transfer when other nearby properties that also stand to benefit (e.g., the many other residential, commercial and hotel projects completed and/or proposed) get a “free ride”? In any event, props to YIMBY for putting this much needed connection between these stations on the table for discussion!

Only a proposal. AFAIK developers have not been contacted. If construction starts tomorrow it will take until at least 2022 to complete if not longer. You can’t force a developer to build the connection.

Still wont happen.. At least terminal Queens Plaza station E,R,M connection to Queensboro plaza station N , Q, 7.. When you have Sunnyside Yard Amtrak , New Jersey Transit rail yard need to be expanded & when you have Long Island Rail Yard Steinway street yard need rebuilt , Long Island City station or Hunters Point avenue LIRR station need rebuilt… etc. How can these project be deal with. Rebuilt Sunnyside Yard Amtrak yard , New Jersey Transit rail road , when think Queensboro plaza station later etc. 1. Rebuilt Sunnyside yard Amtrak yard , Rebuilt Hunter Points Avenue Long Island Rail Road

about time…

Great idea.

So congestion could reach “dangerous levels” once the L train shuts down, but no real mention of what happens to these levels after all of the towers are completed? I am more worried about all of the people they are introducing to the neighborhood through all of the current and proposed residential/hotel development. Again, Court Square is very much overdeveloped.

An elevator to the mezzanine of the Queensboro Plaza station in the median of the elevated structure likely isn’t structurally possible – the top of the elevator shaft would vertically intrude into the 7-train track above. Plus, to make the station ADA-compliant, you would have to add a second elevator between the mezzanine and the two platforms above; since the platforms are right above the roadway, the bottom of any elevator installed to the platforms would vertically intrude into the roadway space below.