In general, new construction reflects local real estate demand and community needs. But given New York’s position as a global economic hub, it is not surprising that one of the city’s largest engineering efforts is a direct response to a megaproject 2,200 miles away. The suspended roadbed of the 84-year-old Bayonne Bridge, which spans the Kill Van Kull strait between Staten Island and Bayonne, N.J., is too low for passage of the latest, giant container ships built to traverse the expanded Panama Canal locks. If the Port of New York and New Jersey fails to accommodate such vessels, the nation’s largest metro area would suffer considerable economic damage. To keep up with the canal’s expansion, slated to open later this year, the Port Authority is raising the bridge roadbed from 151 to 215 feet above the mean water level. The Navigational Clearance Project is expected to cost $1.3 billion. The principal contractors are Skanska Koch, Inc. and Kiewit Infrastructure Co., which are also collaborating on the Kosciuszko Bridge replacement span over the Newtown Creek between Brooklyn and Queens. The Port Authority expects the Bayonne project to generate around 2,800 construction industry jobs with between $240 and $380 million in wages.

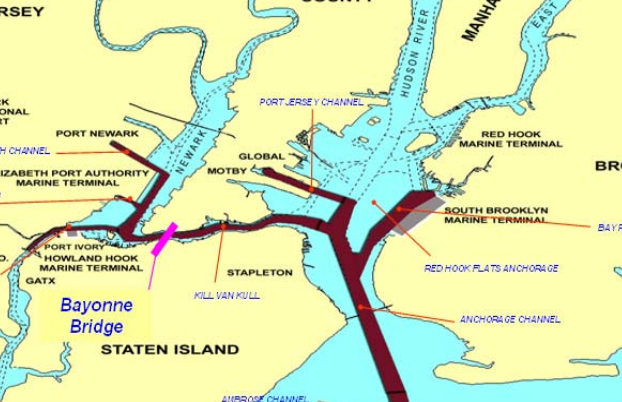

The Kill Van Kull is among the key shipping channels in the third-busiest port on the East Coast, providing access for oceangoing container vessels to New Jersey’s Port Newark-Elizabeth and Staten Island’s Howland Hook marine terminals. Combined, the ports produce close to 270,000 direct and indirect jobs and nearly $11 billion in annual wages. An estimated 12 percent of all international containers entering the United States pass under the bridge.

The hyperbolic curve of the 325-foot-tall, 85-foot-wide steel arch runs 1,675 feet from shore to shore. Until the ongoing reconstruction, the deck it supported was close to 50 feet in width. The profile of the arch increases in depth from crown to abutment, with 37-and-a-half-foot-deep trussed ribs at the top and 67-and-a-half-foot ribs at the ends. The New Jersey and Staten Island approach viaducts are supported by several dozen concrete arches and measure 3,010 and 2,010 feet respectively. The steel arch was the world’s longest of its kind from 1931 to 1977, and remained the world’s longest through arch bridge (where the deck is suspended below the arch) until 2003. It is still the world’s longest through arch bridge outside of China.

Despite its delicate grace and record-breaking engineering achievement, the span, tucked away on a remote, industrial corner of Staten Island’s North Shore, the landmark(*) barely made a dent in the city’s pop culture psyche. Its anonymity is particularly intriguing given the fame that the similarly sized and aged Sydney Harbour Bridge has garnered around the globe.

For the most part, the impressive span was a practical response to complex conditions. The Kill Van Kull, a three-mile-long tidal strait, separates Staten Island to the south from the Bergen Neck peninsula to the north, where the town of Bayonne, New Jersey sits between the Upper New York Bay and the Newark Bay. The name “Kill Van Kull” has Dutch origins, dating back to New Amsterdam. It roughly translates as “channel from the ridge,” in reference to its route between the Staten Island highlands and the peninsula’s Bergen Hill.

In large part thanks to its harbor, New York became the world’s largest city by the beginning of the twentieth century. By the 1920s, the city was entering its greatest bridge-building period, which would last until the beginning of World War II (when a Bayonne facility on the Kill shore would house an Italian POW camp). First studies for a Kill Van Kull Bridge began while the fraternal spans of Goethals and Outerbridge over the Arthur Kill, the island’s first fixed crossings to the mainland, were under construction (incidentally, construction is also ongoing at the twin replacement bridge for Goethals, though it has nothing to do with higher navigational clearance). Inquiry into financial feasibility was completed by 1927, pegging the estimated cost at $16 million (around $219 million adjusted for inflation in 2016).

Although the Kill averages around 1,200 feet in width between pierhead lines, the bridge was not built across the narrowest point. Instead, economy of approach was the deciding factor. The selected site ran parallel to an existing ferry between Bayonne and the Port Richmond neighborhood in Staten Island by the western terminus of the Kill. Though this plan put the bridge at 58 degrees to the shore, requiring a longer, askew crossing with a clear span width greater than 1,500 feet, it preserved existing street patterns on both sides, eliminating the need for clearing numerous city blocks for new approaches.

By the 1920s, the city had already pioneered construction of record-setting spans in three principal types. Three suspension bridges spanned the East River, with the Brooklyn Bridge as the oldest and most famous, and Williamsburg Bridge holding the title of the world’s longest from 1903 to 1924 (the third bridge being the Manhattan Bridge). The Queensboro Bridge, America’s longest cantilever span from 1909 to 1917, stood as the fourth East River crossing. Farther upstream, the 1,017-foot-long steel arch of the Hell Gate Bridge had reigned as the world’s longest of its kind since 1917, when it began to carry trains from Queens to the Bronx via Ward’s Island. All three span types were considered for the new Kill Van Kull crossing. The other two Staten Island bridges underway, Goethals and Outerbridge, were cantilevered. However, replicating the design at Kill Van Kull was deemed too expensive. The suspended version was the cheapest, costing half a million dollars less than the arch type. In retrospect, we are intrigued about how modern engineers would have handled a suspension bridge, where it would be much more difficult to raise the road deck, and which would have been more controversial to dismantle, given how iconic each suspension bridge in New York has become. In the end, the arch design carried the day. Despite being more expensive than the suspended option, the arch had the necessary stiffness to support two tracks of rapid transit. The planners figured that transit revenue would justify the added expense.

The new bridge was designed by the all-star engineer and architect duo of Othmar Ammann and Cass Gilbert. Though Ohio-born Gilbert was well-versed in a variety of architectural styles, he received highest praise as a high-rise pioneer. At the 1913 Woolworth Building, he applied the romantic language of Gothic cathedrals to the modern paradigm of the skyscraper, raising its ornate copper roof higher than any other in the world. At 792 feet, the “Cathedral of Commerce” towered above even the loftiest stone dreams of medieval masters. He was twenty years senior to his structural engineer partner Othmar Ammann, who would go on to become the most influential bridge builder of the twentieth century. Although rooted in the utilitarian, the grace of his work elevated his engineering marvels into the realm of the sublime. His poetry of steel echoed across waterways, taking the form of beam and cable anthems that sang with the spirit of the city. By the end of his long career, his portfolio contained the George Washington (1931), Bayonne (1931), Triborough (1936), Bronx-Whitestone (1939), Walt Whitman in Philadelphia (1957), Throgs Neck (1961), and the Verrazano-Narrows (1964) bridges, as well as the 1937 Lincoln Tunnel. But at the time, the career of the Swiss-born master was only kicking into high gear. After working under Gustav Lindenthal, one of the country’s most celebrated bridge designers of the prior generation, Ammann was appointed as the Port Authority’s chief bridge engineer in 1925. While working on the Bayonne Bridge, Amman and Gilbert also crafted the design for the George Washington Bridge 17.5 miles to the north.

Other prominent designers and engineers associated with the bridge included Alston Dana and Leon Solomon Moisseiff.

As seen from the old John Street quarry, Port Richmond, Staten Island. March 22, 1930. Photo by Percy Loomis Sperr via the New York Public Library. Image ID: 730643F

Although approach conditions and mass transit requirements determined span type and length, Othmar’s experience with another steel arch bridge must have played a role, as well. His work with Gustav Lindenthal on the Hell Gate Bridge a decade earlier gave him the necessary credentials for recreating the design on a much greater scale. Besides, Lindenthal and Othmar’s red-painted span at Hell Gate inspired a much larger counterpart on other side of the globe in Australia. Construction at the Sydney Harbour Bridge started in 1923. Upon completion, its 1,650-foot-long arch was set to soar as the world’s longest. By the time the construction began at the Bayonne span, the Sydney bridge was already many years into its construction phase, yet the erection of its arch began only in late 1928. With proper organization and timely construction, Othmar had a shot at retaking the crown from the Australian usurper. Perhaps it is no coincidence that the final length of the Bayonne span beat the one in Sydney by just 25 feet. If the American crew managed to beat the odds by finishing first, they would snatch the record from the front-runner right at the finish line.

The arch is supported by a movable platform. April 30, 1930. Source: New York Public Library. Image ID: 730644F

Construction of a bridge is never an easy proposition, particularly when it is suspended over an active shipping channel. Throughout history, traditional arch bridges were typically built on top of scaffolds that imitated the future arch. Steel giants of the twentieth century, such as those at Hell Gate and Sydney Harbour, were built with “creeper cranes” that crawled along either end of the cantilevered bridge halves. At Hell Gate, the halves were supported with additional reinforcement structures at the shore, while the cantilevered portions in Sydney were anchored by the massive concrete abutments. Neither option was feasible at the Kill Van Kull site, nor could the slender arch halves support themselves. To keep the channel navigable throughout construction, the arch was lifted in sections by hydraulic jacks that rested on relatively small platforms situated in the channel, assisted by a traveling crane along the top. Despite these constraints, the work was so precise that the two arch halves met within just one inch of one another.

Construction at the Bayonne approach. The future site of the Collins Park is in the background. Photo by Underwood and Underwood via the New York Public Library. Image ID: 730838F

A workman labors on a steel girder while a tugboat passes below. Photo by Underwood and Underwood via the New York Public Library. Image ID: 730839F

A gantry is moved along the top of the completed arch to attach steel cables, very similar to the gantry that will be used to repeat the process for ongoing construction. October 30, 1930. Photo by Percy Loomis Sperr via the New York Public Library. Image ID: 730645F

In the end, the Bayonne Bridge ended up looking rather different than its southern hemisphere challenger. The Great Depression, heralded by the stock market crash of October 1929, stripped not only the budget of the average American, but also the stone flesh off the steel bones of Othmar and Gilbert’s masterpieces. The towers of the George Washington Bridge, which were to be sheathed in Beaux-Arts-styled granite, remained exposed as steel frames, which gave the bridge its distinctly modern look. Preeminent modern architect Le Corbusier called its “blessed reversed arch” “so pure, so resolute, so regular that here, finally, steel architecture seems to laugh.” It is not known what he thought of the Bayonne Bridge, which also lost its stone abutments, which would have resembled those of Hell Gate and Sydney Harbour bridges, due to budgetary constraints. One difference that the design does not owe to financial concerns is the suspension system. The road deck hangs upon steel cables rather than the I-beams, such as those used at Hell Gate and in Sydney.

The Bayonne Bridge opened on November 15, 1931. Not only was the bridge open several months ahead of schedule, but it also cost $3 million less than its projected $16 million cost. Adjusted for inflation, its $204 million cost is six times less than the price tag of the ongoing roadbed raising project.

Looking from Staten Island towards Bayonne. Photo by Underwood and Underwood via the New York Public Library. Image ID: 730843F

The ceremony was held just 22 days after the opening of George Washington Bridge. Othmar and Gilbert’s two bridges became not only the world’s longest of their respective types, but also the highest crossings in the city. The Bayonne road deck features 151 foot clearance above the strait, allowing for the US Navy’s tallest ships to pass beneath. The Palisades-bound span of the GWB runs even higher, with 212 foot clearance above the Hudson River water. The American Institute for Steel Construction apparently disagreed with Le Corbusier’s claim that the Washington span is the “only seat of grace in the disordered city” when they awarded the Bayonne Bridge the “Most Beautiful Steel Bridge” prize for 1931. Time magazine called the bridge’s symmetry and detail “impressive and haunting.” The French city of Bayonne sent their congratulations via a telegram.

Photo by F.S. Lincoln via the New York Public Library. Image ID: 730845F

Original sidewalk. Photo by F.S. Lincoln via the New York Public Library. Image ID: 730642F

Photo by F.S. Lincoln via the New York Public Library. Image ID: 730857F

Ultimately, the American bridge beat its Australian counterpart by four months and four days, even though its 1928 construction start came five years later. Part of its speed advantage came from the span’s lighter design. The steel of Bayonne’s minimal, slender arch weighs 16,000 tons, a fraction of Sydney’s 37,000 tons. The 440-foot-tall Sydney arch rises 117 feet higher, and its 161-foot-wide arch is twice as wide. The Australian bridge originally accommodated six lanes of traffic, two tram tracks (now replaced by two additional traffic lanes), two railway tracks, and a pedestrian path. For comparison, Bayonne’s deck carried only four lanes of traffic and a narrow walkway. Sydney’s 292-foot-high concrete pylons faced with granite add even more gravitas, resembling Cass Gilbert’s original proposal for the New York span. Despite losing the record title they vied for, Australians displayed good sportsmanship. Their ambassador presented a Harbour Bridge rivet to the chairman of the Port Authority. The set of golden scissors, inlaid with opals, that was used to cut the opening ribbon at the Bayonne span, was later sent to Sydney, where the ribbon was cut by the premier of New South Wales on March 19, 1932.

Original Staten Island approach, before freeway construction. Looking from Morningstar Road and Walker Avenue. May 17, 1938. Photo by Percy Loomis Sperr via the New York Public Library. Image ID: 730652F

Looking northeastward from Forest Avenue near Simonson Avenue in Staten Island. October 30, 1936. Photo by Percy Loomis Sperr via the New York Public Library. Image ID: 730652F

Unfortunately, the average New Yorker largely forgot the mighty bridge soon after its completion, as it sat well out of the way of the average commuter’s path. Even now, with 19,378 vehicle crossings per average day in 2011, the Bayonne crossing is by far the least trafficked among the city’s major bridges and tunnels. For comparison, in the same year, Staten Island’s three other bridges – the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, Goethals Bridge, and Outerbridge Crossing – averaged 182,676, 77,691, and 80,101 daily trips respectively. The George Washington Bridge, the world’s busiest, carried 276,150 vehicles per average day during the year. The three Staten Island spans carried even less traffic until the 1964 completion of Verrazan-Narrows, Othmar’s last major commission, made Staten Island a viable transit option between New Jersey and Brooklyn.

The bridge as seen from Bayonne. Looking southwest. Source: The Hudson Reporter, May 1, 2013 / hudsonreporter.com

Thankfully, the bridge held much greater cultural relevance on the other side of the Kull, quickly becoming an icon for Bayonne. It remains an object of pride for its residents, which currently number 63,000 after peaking at almost 89,000 in 1930. The arch caps southbound street vistas, rising in a picturesque curve above the low-slung skyline. The bridge effectively co-starred in the 2005 big screen adaptation of H.G.Wells’ science fiction classic War of the Worlds, sharing the spotlight with Tom Cruise and Dakota Fanning. The terror in the eyes of young Dakota’s character, who looks upon the collapsing bridge that crushes Bayonne homes with falling cars and trucks, is a signature shot that helped propel the child actor to global fame.

2005 was not the first time the bridge inspired lovers of science fiction and fantasy. Decades earlier, the Kill Van Kull had a formative influence on George R.R. Martin, prominent science fiction writer and author of bestselling fantasy series A Song of Ice and Fire. The books serve as the basis for HBO’s hit show Game of Thrones, which expects to smash another set of records as its sixth season premieres this coming Sunday. In 1952, when Martin was four-years-old, his family moved to LaTourette Gardens, a brand-new, low income housing project at 35 East First Street, facing the water ten blocks east of the bridge. His working-class family did not own a car, so aside from yearly trips to the city “to see at show at Radio City Music Hall or something like that,” the boy never strayed far from home.

“I went to school on Fifth Street, and that was pretty much my world, from First Street to Fifth Street, except in my imagination, because I was a voracious reader of books and science fiction books and fantasy books, and all of that stuff,” the author recalled in a 2013 New Jersey Monthly interview. “[Our apartment] faced directly to First Street, and across that was the Kill Van Kull, and the lights of Staten Island would be beyond that, and I think that actually had an effect on me, because I would look off on the waters of the Kill Van Kull. There were always big ships on the way to Port Newark, going up and down there, you know freighters and oil tankers and things like that with flags from all over the world. I had an encyclopedia with a list of flags in the back, so I would look at all these flags of China and Liberia and England and Denmark and whatever, and I learned all the different flags and I tried to imagine what it would be like to be voyaging on some of these ships. And across the way was Staten Island and the lights of Staten Island which were… the great beyond. And once again, occasionally we would cross the bridge and go over to the Staten Island Zoo or take the ferry across, since they had a ferry in those days, but again, that was only like once a year or something, and mostly Staten Island was Shangri-La to me. It was just lights shining on the water, lights of people that I would never see, people that I would never touch, but it really, I don’t know, kindled my imagination.”

We do not know whether the observant author-in-training noticed that as he grew up, his beloved ships steadily grew in size, as well. After World War II, merchants discovered that transporting cargo with standard-sized containers dramatically reduced shipping time, costs, and labor requirements in comparison to traditional methods. In addition, economies of scale apply to ship size, since the bigger the vessel, the fewer ships, laborers, and fuel is required to transport the same amount of goods. While the first, 1960s generation of container ships carried 1,700 TEUs (aka the equivalent of a 20-foot container), the vessels of the 1970s carried around 2,300 TEUs, and the ships of the 1980s could fit anywhere between 4,100 and 5,000 units. These were described as the Panamax class since they maxed out the capacity of the Panama Canal locks, an important consideration for China-bound vessels. Their masts rose close to 140 feet, more than twice as high as those of the first generation and only ten feet below the Bayonne Bridge clearance. Their draft (the underwater portion) has increased in depth respectively, from 20 to over 40 feet. The Post-Panamax generation of the 1990s and 2000s increased carrying capacity to almost 10,000 TEUs. Not only are such ships too large to pass through the canal, but they are also too tall to freely move beneath the Bayonne span. Their crews must remove the top masts, add ballast to weigh the ship down, and/or wait for low tide, which is an expensive luxury in an industry where on-time delivery is paramount. Once the vessel gets moving, watching a Post-Panamax making a close pass beneath the bridge is a spectacle to behold. But as ships grew ever larger, even these measures would soon be insufficient.

New Pacific Locks for Post-Panamax ships are nearing completion, with water retention basins on the foreground. Source: Panama Canal official site – http://micanaldepanama.com/

Beginning later this year, Post-Panamax ships would be able to easily travel to and from China thanks the Panama Canal Expansion Project. It will introduce two new sets of locks (one each on the Atlantic and Pacific sides), widen and deepen the channels between the locks, and raise the maximum operating water level of Gatun Lake in the middle of the canal, doubling the waterway’s carrying capacity and introducing New Panamax as a viable class. Despite prior delays, the project is reportedly 97 percent complete, with the grand opening scheduled for June 26.

The new ships would need deeper waterways to pass across the New York Harbor. Though a network of dredged channels already lines the harbor floor, including one in the Kill Van Kull, the Port Authority, in conjunction with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is deepening the strait from 30 to 50 feet. Although the bulk of the work is complete, there are still areas that require attention. In many places, the sandy bottom has been excavated down to bedrock and requires blasting.

Dredged channels in the Port of New York and New Jersey. Source: the Port Authority via blog.tstc.org, 9/6/2013

While channel deepening is a conceptually straightforward issue, accommodating greater ship height, or air draft, proved more challenging. In Charleston, S.C., the twin cantilevered spans of the Grace and Pearman bridges presented 155-foot clearance over the Cooper River, four feet higher than that of Bayonne. When their clearance became an obstacle to vessels bound for the country’s fourth-largest container port, they were replaced with the mighty cable-stayed span of the 2005 Ravenel Bridge. The steel arch of the Gerald Desmond Bridge in Long Beach, CA boasts the same 150-foot clearance. It prevented the first Post-Panamax vessel from entering the port in 2012. The aging bridge is also about to be replaced by a cable-stayed bridge with a clearance of 205 feet.

By 2009, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers completed their study for addressing the problem at the Kill Van Kull. Three options were considered. Replacing the bridge with a new tunnel proved to be not only the least visually appealing, but also the most expensive ($2.2 to $3 billion) and time consuming (requiring around 15 years for completion). The study also contemplated following in the footsteps of Charleston by replacing the old bridge with a higher cable stayed span. While the proposed structure looked impressive, the original bridge, dismantled down to its steel arch, made for a rather odd sight.

Image hosted at www.nj.com

More importantly, the new span’s $2.15 billion price tag and 13-year-long timetable were less appealing than a roadbed-raising project on the existing arch, which would cost $1.3 billion and may be finished as early as 2019.

Illustration of concept. Source: PANYNJ

Image via www.nj.com

The final plan revolves around raising the road deck by 64 feet, increasing navigational clearance from 151 to 215 feet. The dry title of the “Bayonne Navigational Clearance Project” is mitigated by the snappier slogan of “Raise the Roadway.” Its upgraded clearance would beat that of the George Washington Bridge by three feet, second only to the Verrazano’s 228 foot clearance above the Narrows. The approaches would sit on higher pillars spaced much farther apart from one another than their current counterparts. The suspended road deck’s 30 current segments would make way for around 22 new ones closer to the top of the arch, shortening its length from approximately 1,250 feet at the moment to around 920 feet.

Moving the deck closer to the top of the arch would cost the bridge some of its grace, throwing off its original proportions. On the other hand, the new roadway will provide a safer and more spacious travel experience. The original deck consisted of four 10-foot-wide traffic lanes, with no shoulders nor barrier to separate the opposite directions of traffic. The maximum overhead clearance clocked in at 14 feet. A 6-foot-wide walkway ran along the western side. Though the walkway is now gone, you may get a glimpse of the experience via Forgotten New York’s 2012 walkthrough. The new deck will feature 12 foot traffic lanes with 6′-6” shoulders, with northbound and southbound traffic separated by a concrete median. Although rapid transit lines are still not included, provisions have been made for possible future implementation. A 12 foot shared use path for pedestrians and cyclists would now run along the east side of the span. After ascending the man-made steel mountain suspended over the strait, visitors would be treated to one of the most breathtaking skyline views in the metro area.

Looking northeast from the old pathway. Not only would the new walkway sit 64 feet higher, but its location on the other side of the bridge would offer unobstructed views. Photo via forgotten-ny.com, November 2012.

The vista would be comparable to the views that would open from the 630-foot-tall, harbor-facing New York Wheel rising on the other end of the Kill Van Kull. In the meanwhile, the best alternative for pedestrians would be the free shuttle across the bridge provided by the Port Authority during weekends from May through October.

In March of 2012, the agency was among the first in the country to apply for President Obama’s 2012 We Can’t Wait Initiative of expedited infrastructure projects. On April 24, 2013, the Board of Commissioners awarded a $743.3 million contract to Skanska Koch, Inc. and Kiewit Infrastructure Co. as part of a $1.29 billion budget for raising the roadway.

The Bayonne approach. Looking south. Source: Reena Rose Sibayan for The Jersey Journal. May 13, 2015.

Though the road-raising option is the cheapest and fastest, it also requires the most creative engineering approach. While the city has not added a new deck to an existing bridge since the lower level of the George Washington Bridge in 1962, the concept of adding a new, partially suspended roadway over an existing one is altogether new. When the bridge was first built, the architects and engineers had to be mindful of the ship traffic passing beneath the new structure. The current generation has to be considerate of vehicle traffic, as well. Though the frequent bridge closures are announced ahead of time on the Port Authority’s website, commuters are not thrilled by the major inconvenience. However, given the project’s complexity, it is a testament to the builders’ ingenuity that they are able to keep the bridge functioning at all while construction is ongoing. Elevated over a hundred feet above ground and tightly sandwiched between an active roadway and neighborhood backyards, the first (and ongoing) phase is a delicate ballet of dismantling and rebuilding half of the span while the other half carries one lane of traffic in each direction. The second phase consists of suspending the upper deck under the arch while using the existing roadbed for staging. The last phase would see a repeat of phase one for the remainder of the approach, while the built portion would temporarily carry traffic in both directions. You can see a simulation of the process here, or follow along with the Port Authority’s official video.

Phase 1: Partial new approaches

Step 1: Dismantling of the sidewalk while reducing traffic to one northbound and one southbound lane.

Step 2: Dismantling of the western half of the roadbed while the remaining two lanes are moved east.

Step 3: Roadway piers are built with precast concrete segments.

Step 4: A rolling gantry transports and places precast road segments for the new approach.

Step 5: Traffic is moved to the new structure while the process is repeated for the southbound side.

Phase 2: Suspended span

Step 1: New deck is constructed above the existing roadway via a rolling gantry moving along the top of the arch. Transfer load beams temporarily support the road while the old suspension cables are removed.

Step 2: New deck road beams are delivered via the old span, lifted and rotated in place, and attached with new suspension cables.

Step 3: Temporary suspender cables support the bottom deck for the duration of construction.

Step 4: Transfer load beams are removed and new stringers are lifted into position.

Step 5: The gantry is advanced and the process is repeated for every new segment. Upon completion, a new concrete deck would be poured on top.

Phase 3 effectively mirrors the process described in Phase 1.

At the moment, the project is inching closer to completion of the first phase, one cantilevered road segment at a time.

Due to the project’s complexity, its original completion has been delayed by two years from 2017 to mid-2019. The somewhat good news is that the delay does not affect ocean-bound vessels, which could take advantage of the increased clearance starting in 2017. Interestingly, bureaucratic obstacles proved as daunting as the engineering challenges. According to the New York Times, the project has generated over 5,000 pages of federally mandated archaeological, traffic, fish habitat, soil, pollution, and economic reports, costing over $2 million. For instance, a historical survey of every building within two miles of each end of the bridge cost $600,000, even though most would not be affected by the project. The environmental assessment considered input from 307 organizations or individuals. Fifty-five federal, state, and local agencies were consulted and 47 permits were required from 19 of them. Fifty Indian tribes from as far away as Oklahoma were consulted on whether the project encroached on native ground. On one hand, a thorough review process avoids embarrassing oversights, such when two Native American tribes were not informed of the Kosciuszko Bridge redevelopment upon their native land, rich in archaeological artifacts. On the other hand, the staggering scope of paperwork filed for the Kill Van Kull span seems like an exercise in obstructionism and red tape.

Despite the incredibly thorough review, some neighbors allege that serious oversights did take place. Although the very title of our blog stands for “Yes In My BackYard,” we understand that massive redevelopment literally behind our backyards can sometimes be frustrating. Controversy unraveled when nearby residents complained of issues such as excessive noise, earth-shaking and house-damaging vibrations, thick layers of dust coating the neighborhood, and even large paint chips falling off the bridge onto their property. The Port Authority addressed the complaints in a public statement, where it claimed to follow city noise codes while implementing a noise mitigation policy, and offered up to $10,000 for properties subject to excessive noise to upgrade to soundproof windows. While neighbors complain that the money would come with a blanket “gag order” in regards to all future complaints regarding the project, the Port Authority once again dismisses the claim as misleading. Regardless of which side presents the complete picture, the good news is that most neighbors would have to tolerate adjacent construction for a few weeks rather than the entire four-year duration of the phase-by-phase project. The project’s environmental consolation prize is that the larger ships it would service are capable of carrying the same amount of cargo with less fuel, reducing emissions into local air and water.

The project passes close to neighborhood homes in Bayonne. Looking south. Source: Reena Rose Sibayan for The Jersey Journal. May 13, 2015.

As a kid, George R.R. Martin has saw the lights of Staten Island across the Kill Van Kull as the “great beyond,” full of allure and mystery. In August 2015, the citizens of the island borough paid their tribute to the author by turning their land into a living version of the author’s fantasy, when the Richmond County Bank Ballpark on the St. George waterfront, just downstream from the bridge, hosted a ball game between the Staten Island Yankees and the Hudson Valley Renegades. The two teams took up the banners and jerseys of House Stark and House Lannister, two warring factions of the Song of Ice and Fire novels. The Staten Island Direwolves routed the Lannisters on the ballfield battlefield with a score of 10-1. This brief but entertaining episode underscores not only the physical, but also cultural closeness of the two communities on either side of the Kull. The islanders treated the peninsula-born guest of honor as one of their own, even though he was technically from another state. If the two cities on either side of the strait invest in mass transit by running a rail line across the bridge as initially planned, the motion would vastly expand the growth potential of both communities.

The stage is all set for such development. As mentioned earlier, the arch was chosen in the first place due to its ability to carry rail, and the ongoing upgrade maintains the mass transit option. The south terminus of New Jersey’s Hudson-Bergen Light Rail, which serves several cities along the Hudson County, stops at 8th Street Station just a few blocks northeast of the bridge. The rail line is purposefully oriented with a future bridge expansion in mind. And although a bus route has recently been introduced to service the two sides of the bridge, there have been many calls for extending the light rail instead.

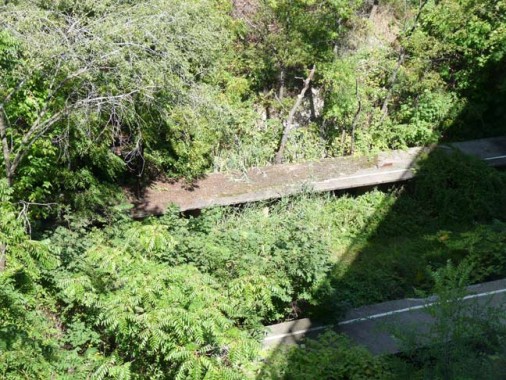

The extension would be most effective if carried out in tandem with a Staten Island upgrade. Until 1953, the North Shore was serviced by a branch of the Staten Island Railway, which ran from the St. George waterfront, the destination of the Staten Island Ferry, and the Mariners Harbor neighborhood west of the bridge. The railway’s abandoned Elm Park Station is still visible at the foot of the bridge.

The original path of the Staten Island Transit line. Note the Elm Park Station at the foot of the bridge. Image via forgotten-ny.com, July 1999.

Elm Park Station. Photo by Doug Douglass via forgotten-ny.com, July 1999.

The ruins of the Elm Park Station as seen from the bridge approach. Photo via forgotten-ny.com, November 2012.

A rebuilt Elm Street Station would serve as the western terminus of a rebuilt North Shore line, which would connect to the existing branch at St. George. There, the northeast corner of the island serves as the borough’s focal point. The waterfront park is home to the terminus of the Manhattan-bound ferry, as well as ongoing development of a retail complex and the New York Wheel, which is slated to become the world’s largest Ferris wheel upon completion. Staten Island authorities are making a heavy push to encourage development to keep up with the city’s hot real estate market. Though the North Shore is the most densely populated part of the borough, it still boasts plenty of opportunities for development, particularly given its proximity to the ferry as well as to New Jersey. The Elm Street Station would be used for transferring to the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail, which would connect with the 8th Street Station on the other side of the bridge. For the first time in its history, Staten Island’s isolated rail line would be linked with New York City’s subway network via a North Shore – Bergen-Hudson Light Rail – PATH connection.

Under this scheme, new housing along the North Shore would offer an effective mass transit commute option not only to Lower Manhattan, but also to the growing office districts in Jersey City and Newark. While the scale of the existing built-out blocks does not have to be drastically disturbed, the many nearby empty lots, with a particularly large one just southeast of the bridge, could easily accommodate denser mixed-use development. The neighborhood would also benefit from conversion of largely empty brownfields along the waterfront into a public promenade, which may stretch along Kill Van Kull’s entire south shore, from the park at St. George to the east to the bridge to the west. Even if the plan proves too ambitious, a smaller park may replace the brownfield and auto facility between the bridge and the pleasant but small Faber Park briefly touching upon the shore 2,000 feet to the east.

Staten Island should follow the example set by Bayonne. Though the maritime industry east of the bridge was cleared back in the 1920s, the land sat empty until a baseball diamond went up next to the steel arch in the 1960s. By the 1980s, Dennis P. Collins Park, named after the longest-serving mayor in Bayonne history, transformed former industrial ground in to a 0.8-mile-long waterfront promenade, which stretches to the foot of the LaTourette housing project where George R.R. Martin grew up.

Bergen Point. Looking north from the bridge. Photo by Jim Henderson via Wikipedia.

Major change is already unnderway at the foot of the bridge. In the late 19th and early 20th century, the Bergen Point peninsula directly west of the future bridge was home to stately estates such as the Latourette House, where Samuel Francis Du Pont, a Rear Admiral in the United States Navy, was born in 1803. After the bay’s industrial transformation, the peninsula served as a Texaco facility, until it was cleared in the late 1980’s – early 1990’s. Now, the low-lying, 44-acre lot is being raised 6 to 10 feet in order to accommodate the future Promenade at Bayonne development. A dozen new blocks will house over 1,000 residential units and 60,000 square feet of new office space, served by 134,000 square feet of retail. The peninsula will be ringed by a waterfront promenade, anchored by a series of public squares where the promenade meets the new street grid. The portion closest to the bridge will become an extension of the Collins Park on the other side. The new bridge approach will present a lesser barrier than the original one due to its higher elevation above ground and smaller number of concrete supports. Conceptually, the project is akin to the Hunters Point South development in Long Island City, where a similarly-sized, formerly industrial peninsula is being transformed into a green waterfront community. The increased density introduced to the area by the Promenade at Bayonne would stand as yet another argument in terms of a light rail link across the bridge.

Source: www.minnowasko.com

Source: www.minnowasko.com

The rail link would take significant time and commitment on behalf of the governments, agencies, and developers of both New York and New Jersey. But aside from visions of a more connected, greener future for the Kill Van Kull waterfront, our more immediate suggestion would be to bring back the golden shears from Australia to be used once again at the 2019 dedication of the rebuilt Bayonne Bridge.

Corrections were made on April 24th to address comments by Chris C and Robert Heikkila.

Subscribe to YIMBY’s daily e-mail

Follow YIMBYgram for real-time photo updates

Like YIMBY on Facebook

Follow YIMBY’s Twitter for the latest in YIMBYnews

About 2 hours to read your details, but I understand and see with demonstration of pictures.

No comment of the massive development projects breaking ground in Bayonne this year? Lol or the large 44 acre of land by the bridge which is about to be developed with five to ten story luxury residential buildings?

Another great and exhaustive post but one minor correction. Charleston is in South Carolina.

A brilliant documentation of an American engineering icon.

Great article. Enjoyed reading all the details. Thank you!

Interesting and insightful. Always looking forward to your new publications

Fantastic piece

Nice article! Correction though. It’s the 3rd busiest port in the nation – not on the east coast. Part of the reason this Bayonne project is so important is that ships coming from Asia can pass all the way through instead of stopping in LA and Long Beach. Then NY/NJ could possibly regain the busiest port status as it had decades ago when trade was mostly across the Atlantic. Most of the port activity was in Manhattan and Brooklyn back then – but that’s another story.

I don’t think the USA will be importing much once the Panama Canal widening is complete. Quite the opposite I think the USA will soon be exporting goods in vast quantities…particularly energy products although that will be heading South out of Philadelphia not New York of New Jersey. I’m not sure what Bergen will be importing or exporting actually although you do have Newark Airport which in theory could move goods by air instead of sea. Since most of what is imported into the USA from the world is electronics which doesn’t weigh much I could see Kennedy Airport and Newark as being your major transportation hubs for actual goods. It is interesting to ponder whether the Staten Island Ferry will become a “Back to the Future” mass transit solution to the entire Hudson River Corridor and Beyond. Certainly would appear New York City’s population is set to double again.

Impressive and thorough article. Congrats to the writers who toiled to find the facts as best they could.

I don’t agree.